The doyen and three generations

Walter Grimmer and the 3G Quartet have recorded Schubert's String Quintet in C major. The opening piece is Philippe Racine's Adagio, written at Grimmer's suggestion.

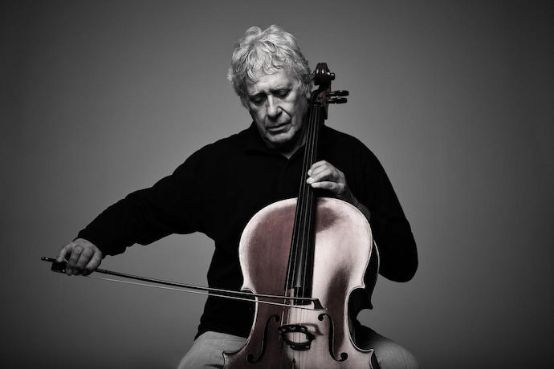

Walter Grimmer has just turned 82. But after a rich musical life, he doesn't want to rest on his laurels. The musician, who is often referred to as the "doyen of Swiss cellists" and who has devoted himself with great passion to new music in particular, now presents a remarkable recording of the Schubert String Quintet in C major with his three-generation quartet 3G, which breathes a touching beauty of sound and intimacy, especially in the lyrical passages. The string sound is precisely tuned, the vibrato as tasteful as it is discreet. Walter Grimmer plays the second cello part, his pupil Sébastien Singer the first; Egidius Streiff, confident but never dominant on the first violin, the young Lisa Rieder on the second and Mariana Doughty on the viola complete the ensemble.

The second movement is a real locus amoenus with the flat, warm chords in the middle voices, before another world breaks in in the middle section, which, however, lacks a little drama to make the extreme contrast composed by Schubert even more vivid. In the opening movement, too, the 3G Quartet, expanded to include a cello, opts for commitment rather than clarity - the crashing staccato quavers have been heard more dramatically before. In the Scherzo, the five sharpen the contrasts between the lusty, gripping and ethereally enraptured middle section. The finale, which starts quite leisurely, gradually unleashes the pent-up energy and is wonderfully free in its music-making. Minor inaccuracies such as clattering pizzicati in the Adagio are hardly noticeable.

The fact that the quintet was preceded by a Adagio for string quintet by Swiss composer Philippe Racine, commissioned by Walter Grimmer, fits in with the Swiss cellist's CV, who has always championed contemporary works and premiered many of them. Here he explicitly requested a work to be played before the Schubert quintet: C major reminiscences meet harmonics, lost trills, tense chords and intimate melodic fragments.

Franz Schubert: String quintet in C major, Philippe Racine: Adagio for string quintet. Walter Grimmer and the 3G three-generation quartet. Solo Musica SM 331

Remarks by Walter Grimmer on Schubert's String Quintet D 956 op. posth. 163

"Since the invention of musical notation, musical art has existed in two aggregate states: as notated and as sounding music. [...] Since the invention of the gramophone record, a third entity has increasingly come between notation and sound, namely the performer."(1)

However, the interpreter's sole aim is to convey the music "in its innermost essence".(2) as a temporally bound sound. A keen awareness of form, the most sensitive sound sensibility in terms of harmony and a mastery of technical and dynamic-dramatic execution are the foundations without which he cannot even venture close to the great masterpieces.

An authoritative interpretation of the String Quintet D 956, Schubert's instrumental swan song, the undisputed pinnacle of the genre, demands a well-founded innovative artistry from its performers; unfortunately, for a long time they have only been able to appropriate the piece in a rather dubious printed edition of the lost manuscript: at the latest since the first edition as "Grand Quintuor" of 1853 by C.A. Spina in Vienna, the manuscript has been untraceable.

Numerous obvious inconsistencies, including careless mistakes that Schubert was no longer able to correct, have strangely also been adopted by the latest so-called Urtext editions. It also appears, always in comparison with other late works by Schubert, that the unknown copyist overloaded the last movement of the quintet in particular with dynamic instructions in an arbitrary and wasteful manner.

This is an obvious example of the dubious authenticity of the surviving text: At the end of the exposition of the first movement, the last dominant seventh chord only makes sense if it is repeated. Under no circumstances is it a 'signpost' to the initial development key. From an editorial point of view, this bar should therefore be marked as the "first exit", whereas the following bar should be marked as the "second exit". Another striking example is the traditional dilution of the form of the third movement and its trio. Its traditional form is also to be re-read here, the coda of course only to be played once - the interpreter truly becomes the creator of meaning. Strangely enough, this fact has not yet been dealt with in the editions and literature on Schubert.

Due to its harmonically moving content, not least because of its temporal extension, its "epic character"(3) of his last works, Schubert seems to have found the "sheltering enclosure"(4) of the sonata form.

Like a leitmotif, the listener experiences the long and consuming swelling and subsiding sounds in each of the first three movements. The final unison C of the last movement is different: What if this was only meant to be an infinite swelling away, a silencing in bottomless depths?

The alternating changes in function and position of the five string instruments - even the viola occasionally becomes the foundation - is one of the ingenious aspects of this quintet; the composer may have further developed the extended bass aura of his "Trout Quintet" D 667 here. The many existing quintets with two cellos, from Boccherini to Onslow, go their own way and have nothing in common with Schubert's visionary vision of almost symphonic chamber music.

This much-played piece, often thrown together ad hoc, often simply with a star guest on the second cello, has been able to retain its high status despite all the inconsistencies. I experienced it as a great opportunity to rethink and "hear out" this ultimate masterpiece again and again over the years.

The weighing up of nuances, the ever-present doubt about the authenticity of the traditional score, the discarding or adding of playing instructions, the formulation of what is not notated, the "learning from the partner" and finally the repeated checking in concert - a passionate musical adventure, for which I have had to wait a long time, has found its harmonious conclusion with this recording.

My deepest thanks go to my friends from the 3Gdreigenerationenquartett; it was only through their unconditional artistic commitment that this recording could be realized.

1) Silke Leopold : About the music. https://www.swp.de/suedwesten/staedte/ulm/silke-leopold-ueber-die-musik-29457622.html, [consulted on July 31, 2019]

2) Ibid.

3) Ernest Ansermet, 1961, Les Fondements de la musique dans la conscience humaine. Neuchâtel, ed. de La Baconnière, p. 420.

4) Peter Gülke, 1973 Schubert. Munich, Ed. text + kritik, p. 150