As traditional as it is individual

In his String Quartets Nos. 1 and 2, Camille Saint-Saëns always immediately corrects and counteracts the proximity to classical models with the unexpected.

Outside the French cultural sphere, the two string quartets op. 112 (1899) and op. 153 (1918) by Camille Saint-Saëns lead a marginal existence. The works of other French composers are too dominant, above all the epochal milestones of the genre by Claude Debussy (op. 10, 1893) and Maurice Ravel (F major, 1904). But the contributions of Darius Milhaud, Gabriel Fauré and César Franck have not been completely forgotten either.

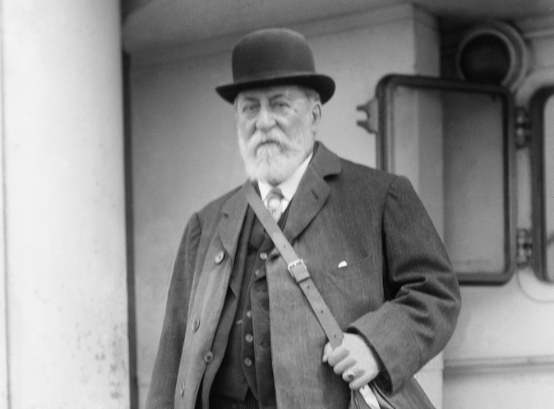

Saint-Saëns is a phenomenon in music history. Like Max Bruch, he never left the path of tonality and some of his works sound out of time. However, while Bruch's Quintet in A minor and Octet in B flat major from 1918/19, for example, could have been written 60 years earlier, the French composer's two string quartets in E minor (1899) and G major (1918) clearly show traits of their time of composition. Saint-Saëns was quite open-minded towards Gustav Mahler and other modernists who followed on from late Romanticism, while he described those who overturned the known laws and forms, such as Igor Stravinsky, Debussy and the group Les Six, as "madmen".

His music is always technically flawless, characterized by great sophistication and ingenuity as well as captivating melodies. At the same time, it is always closely linked to tradition and anchored in the formal principles that have evolved over the centuries. At the same time, however, it is full of surprises, brilliant ideas and effects that cannot be found elsewhere. It thus characterizes the individualist Saint-Säens, who has often been unjustly called backward simply because he did not want to follow the upheavals of the 20th century. For he constantly mutated in his own style, the only one available to him, even if he occasionally chose to go backwards. It is also possible to be innovative in an ancestral language that makes its roots recognizable. It should not be forgotten that the composer was a fiery pianist and musician to the very end.

The two quartets are very different. Due to its length of 30 minutes alone, the 1st String Quartet towers above its counterpart of Haydnian brevity, written almost a generation later. The Bärenreiter publisher's announcement states that the form and style of the quartets refer (among other things) to the aesthetics of this great father of the genre. This is sometimes shockingly true in the 2nd Quartet, but as a sales argument or stigma - depending on how you look at it - it falls far too short. The composer always corrects and counteracts this closeness immediately with the unexpected, for example with grandiose, complex fugal techniques. In the more traditional late work, the deeply felt slow movement is particularly engaging, which can certainly be understood as an allusion to the devastation and sadness of the time. The 1st Quartet, much played by the great stars of the string scene in the French-speaking world immediately after its publication (e.g. by Eugène Ysaÿe and Pablo Sarasate), is nothing less than an unqualified masterpiece. With its rich harmonies, counterpoint and effect passages, rhythmically gripping like the Scherzo, grateful strings and full of passionate melody, it deserves its rightful place alongside the works of the famous late Romantics.

Camille Saint-Saëns: String Quartet No. 1 in E minor op. 112, parts, BA 10927, € 32.95; String Quartet No. 2 in G major op. 153, parts, BA 10928, € 34.95; No. 1 + 2, study score, TP 779, € 29.95; Bärenreiter, Kassel