Facets of virtuosity

This English and German-language anthology takes a broad look at the subject of the violinist Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst. A CD with musical examples rounds off the publication.

In the last decade, the concept of virtuosity has expanded from virtuosos and their works to encompass broader questions of a new artistic landscape and new performance practices. The starting point for this book, whose point of reference is the violinist and composer Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst (1814-1856), was the conference "The Long Shadow of Paganini" in Göttingen in November 2015. The papers by 19 authors, half in English and half in German, provide a look back and a look forward and are divided into six sections: Different Concepts of Virtuosity, Musical Text and Performance, Salon versus Concert Hall, The Wide Field of Virtuoso Performance Practice, Virtuoso Careers, Impact in the Press and Literature. It is almost impossible to report briefly on all of this! I have therefore selected a few exciting highlights:

H. W. Ernst is the performer of his virtuoso compositions who tours all over Europe and is financially dependent on full halls (and they are overflowing!). He is the antithesis of Joseph Joachim, the music professor who seriously fights for faithfulness to the original. Both are child prodigies and establish themselves as Romantic heroes in the halls and salons of an increasingly bourgeois Europe in the 19th century, like Chopin, Auer, Paganini, Liszt, Thalberg, Saint-Saëns, Vieuxtemps, Sivori and Kreisler. The virtuoso flow of the performer's personality brings the listener to emotional ecstasies. Kreisler says: "If you have virtuosity in your blood, the pleasure of stepping onto the podium makes up for all your troubles. You should play for free. What am I saying? You should pay to play!"

The reflections on the word dolce, the instruction that occurs most frequently in Paganini's works and in the first movement of Beethoven's Violin Concerto, show that great emotional commitment is required of the performer (Paganini: "Bisogna forte sentire per far sentire"). Ernst places dolce at the culmination point of his works, which corresponds to the golden ratio of the bar numbers. Heine writes that finger dexterity can only produce a credible performance when combined with a heartbeat so close to that of the violin. Borer comes to the conclusion that dolce does not mean piano, but rather a poetic-ethical - particularly intense - dimension beyond musical dynamics that promotes greater depth. Examples: Tartini ("suonare parlante"), Corelli ("Prince of Sweetness"), Dante (Purgatorio XXIV, 52-57: "dolce stile novo"). The church fathers Augustine and Caesarius of Arles believed that with a string stretched on a piece of wood - like the body of Christ tied to the cross - it was possible to "express the sweetness of truth". The ancient Greeks (Orpheus, Pythagoras) associated string playing with sweetness, love and strength; Amphion built the walls of Thebes with string playing. And the Indian Bharata considered sweetness (madhura) to be one of the nine important qualities of music.

There is something better than perfect violin virtuosity; an anonymous 30-year-old violinist sums this up by saying: "It's much harder to be technically perfect and emotionally involved at the same time, because you take risks." Gidon Kremer demands that there is something in a performance that makes it "personal, human and deep". The Latin meaning of the word imperfectus means "unfinished, unfinished" - in other words, "still searching, alive"! Since the beginning of the 20th century, the "performance police" of studio recordings have seduced us into smoothness and prevented "reaching for the unattainable. Perfection kills art" (Kremer). Many performers have defended themselves against this with long uncut recording sequences or live recordings. Artur Schnabel said that recordings were "against the true nature of performance". Rudolf Serkin regarded recordings as "torture". Popular musicians succeed in the battle against the microphone with improvisation - which is unique, uncuttable; very much in the spirit of Mozart and Beethoven, who did not write down their solo parts during performances. The example of Patricia Kopatchinskaja's unconventional concert practice shows how one can leave the "fool's house" of virtuosity.

One chapter delves into the hardships and successes of H. W. Ernst's five-month tour to the Netherlands. Here is a quote from the many press reviews: "One sees [when looking at the audience] sad, melancholy or loving facial expressions, depending on the tones the artist produces. ... If the artist knows how to bring it so far that our soul is united with his, then he has reached a high level of perfection."

Further chapters provide a breathtaking summary of Camille Saint-Saëns' 80-year virtuoso career. Heinrich Heine's fascinating, amusing and provocative reports on Parisian musical life are described. We learn about Louis Spohr's findings with his colleagues Ernst and Sivori in London in 1843 about thin strings = light harmonics versus thick strings = full tone. The lives of the sisters Teresa and Maria Milanollo provide an opportunity to reflect on a female form of violin virtuosity. Poetic works by Dostoyevsky and Gautier are used to compare Ernst's different impact in Western Europe and Russia.

On the CD you can compare different interpretations - played at a high level - of works by H. W. Ernst. Based on original fingerings, the type of glissandi common in the 19th century is demonstrated.

This stimulating book lacks an index for specific searches.

Christine Hoppe, Melanie von Goldbeck, Maiko Kawabata eds: Exploring Virtuosities. Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst, Nineteenth-Century Musical Practices and Beyond, 413 p., CD with musical examples by H. W. Ernst, recorded by authors of the book, € 74.00, Olms, Hildesheim et al. 2018, ISBN 978-3-487-15662-0

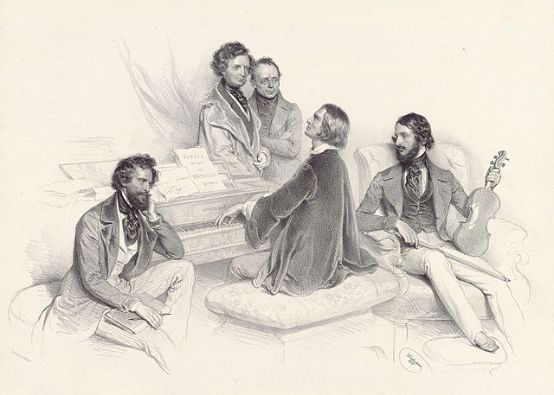

Picture above:

A matinee with Liszt, engraving by Joseph Kriehuber (1848)

from left: Joseph Kriehuber, Hector Berlioz, Carl Czerny, Franz Liszt, Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst.

Bibliothèque nationale de France/wikimedia commons