Richard Flury - a romantic?

Chris Walton has traced the life and work of the Solothurn composer Richard Flury (1896-1967). In addition to the detailed English-language biography, a short German summary with a list of works is also available.

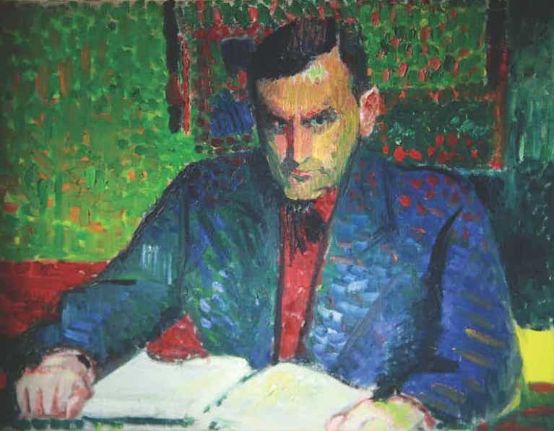

"S isch immer e so gsi" - Chris Walton thought he could hear Solothurn's musical motto himself when writing his Richard Flury biography in English, which is well worth reading and based on extensive unpublished material (p. 102/3). His biography of the composer, who was born in Biberist and educated in Basel, Bern and Vienna, which includes a complete list of his extensive oeuvre and a CD with a successful selection of historical recordings and new recordings, also deals fundamentally with his self-prescribed musical anachronisms.

It takes a good 200 entertaining, richly illustrated and strictly chronological pages for Fleisch to get to the romanticisms of the composer, born in 1896, already mentioned in the book title. A pleasantly underlined view of German-speaking Switzerland from the outside (What does flour soup taste like? What do the Table Mountain and the Weissenstein have in common?) leads to an argumentative derivation of the romantic Flury from a complex of provincialism that has never been overcome, and states a spiritual refuge that has been defined here, to which there would certainly have been alternatives. Strong passages are found in the localization of this interesting composer figure in the Swiss education and music training system (Flury worked as an orchestra director and cantonal school teacher in Solothurn), also in comparison with his Swiss professional colleagues, who, in contrast to Flury, all fell almost completely silent in old age (pp. 95, 113).

Walton's authorial perspective, which seeks to pass final judgment on the good and bad of the music, does not fundamentally question this ultimately self-isolationist figure and places the book in a progressive mindset that the composer had just opposed. Thus, the "most modern" and shortest works of the 1920s with tendencies towards atonality and Gebrauchsmusik are described as the best and still worth performing today.

To pursue in depth the romanticisms that are particularly pronounced in his later works would probably also have meant a clearer examination of Flury's - probably not physically consummated (p. 189) - preference for very young girls, which is documented as a source of inspiration in some unpleasant passages in his correspondence with his teacher Ernst Kurth (p. 124) and in the dedications, especially of his songs and chamber music. It would have meant not shying away from a discussion of his religiousness (with excommunication after divorce and readmission after a vow of celibacy) in order to understand his sacred compositions (and a transfiguration of these girls into the role of Madonna). Presumably, all this was not easy to implement in a book that was written in close collaboration with his son from his second marriage and with the support of the family foundation. "S isch immer e so gsi".

In the Small series A 30-page biographical outline and an abridged catalog raisonné in German have been published by the Solothurn Central Library:

Chris Walton: Richard Flury (1896-1967). A Swiss Romantic, Small Series Volume 5,

41 p., Fr. 20.00, Central Library Solothurn, 2017, ISBN 978-3-9524247-2-8

Chris Walton: Richard Flury. The life and music of a Swiss romantic. 328 p., £ 25.00, Toccata Press, London 2017, ISBN 978-0-907689-44-7