The "grande dame" of "bonne grace"

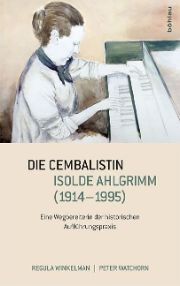

A biography of Isolde Ahlgrimm (1914-1995), an important figure on the road to historical performance practice, translated and expanded from English.

The fact that the rediscovery of early music and the turn to historical performance practice was neither the result of a revolution nor without influential personalities is made clear by the book The harpsichordist Isolde Ahlgrimm (1914-1995) clearly. A generation younger than Wanda Landowska (1879-1959), Isolde Ahlgrimm relied more uncompromisingly than Landowska on teaching works and musical sources from the past; half a generation older than Gustav Leonhardt (born 1928) and Nikolaus Harnoncourt (born 1929), she was a source of inspiration for these pioneers and - despite all differences of opinion - a supporter, at times even a musical partner. She trained as a pianist at the Vienna Academy of Music and, at the age of twenty, met the controversial collector and charismatic advocate of unconditional fidelity to the original, Erich Fiala, whom she married in 1938. While performances of Mozart's keyboard works on the fortepiano were initially the focus of her own "Concerts for Connoisseurs and Lovers", from 1943 she turned to the (pedal) harpsichord and thus to the keyboard works of Johann Sebastian Bach, which she recorded (almost) in their entirety between 1951 and 1956. After her divorce from Fiala, this finally opened the door to an international career and a teaching position at the Vienna University of Music. Until 1983, she gave concerts at home and abroad, as far afield as the USA and Japan, and was a particularly frequent and popular performer in Switzerland. Isolde Ahlgrimm died in Vienna on October 11, 1995.

In many ways, Ahlgrimm was far ahead of her time. First of all, this concerned her meticulous work with sources, thanks to which she compiled a compendium (posthumously edited in 2004) of the Ornamentation of music for keyboard instruments could compose. On the other hand, she decided (all too) late, in 1972, to play on real copies of historical instruments and remained faithful to her Ammer harpsichords with their long (piano) keys. She rejected certain mannerisms of her younger (especially Dutch) colleagues and relied on a multitude of historical statements and examples. Even in her insistence on professionalism and technical perfection, she always remained a supporter of good taste or, as she herself said, "bonne grace".

The expanded and enriched translation of an English biography of her last student Peter Watchorn from 2007 by another former student, the Swiss Regula Winkelman, rightly draws attention to the work of the important Viennese harpsichordist as a preliminary collection of material. The reprinting of Ahlgrimm's own accompanying texts to the complete Bach recording is particularly commendable; in their complexity and wealth of ideas, they are indispensable documents of Bach's reception in the 20th century.

Regula Winkelman, Peter Watchorn: The harpsichordist Isolde Ahlgrimm (1914-1995). A pioneer of historical performance practice, 288 p., hardcover, € 29.99, Böhlau, Vienna and others 2016, ISBN 978-3-205-79679-4