Deciphering musical notation

A cursory overview or an in-depth guide to reading and interpreting. Two different books on the same topic.

-

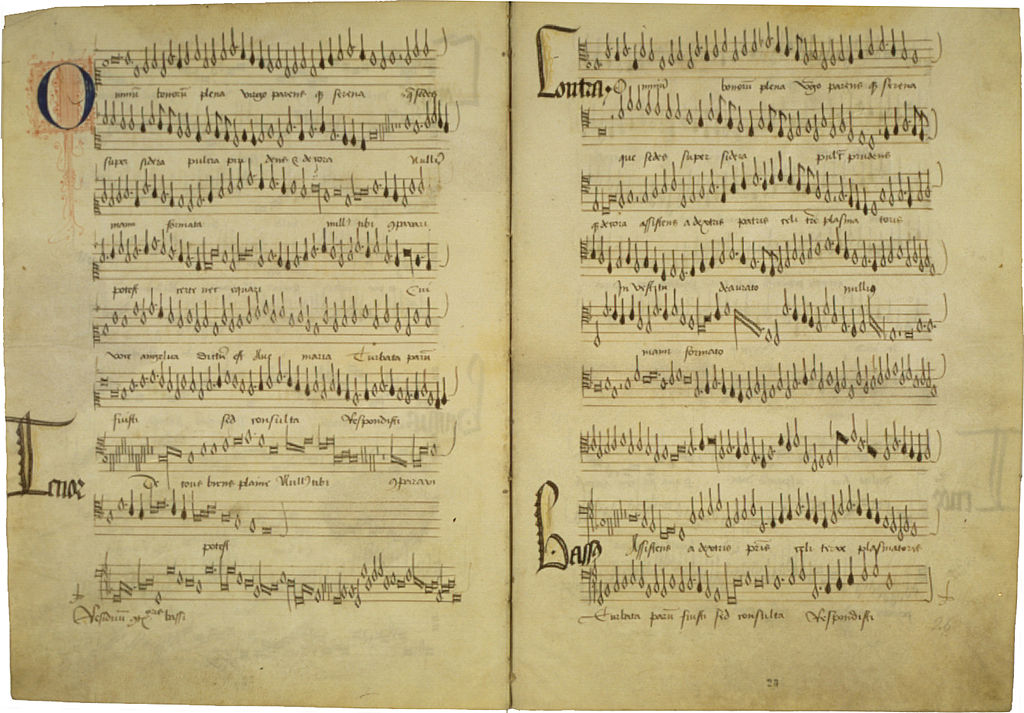

Manuscript with the Omnium bonorum Plena, a motet by Loyset Compère, ca. 1470. Wikimedia commons

After half a century of only Willi Apel's The notation of polyphonic music (English 1942, German 1962) introduced the reading of original sheet music, two new textbooks on early music notation have now been published. However, although both are entitled "Notationskunde", they could not be more different; a comparison would be like comparing apples and pears. The book by Schmid, professor emeritus of musicology from Tübingen, is largely similar to Apel's, while Paulsmeier, who taught the subject for 30 years at the Basel Academy of Ancient Music, presents something completely independent.

Schmid's aim is to present the development of musical notation from the Middle Ages to the year 1900, with glimpses of ancient predecessors, neumes, tablatures, etc. A central concern for him is to "awaken an understanding of the functions of writing and its active role in the process of compositional history". The very clearly laid out chapters are regularly accompanied by tasks in which, for example, original notation shown in facsimile is to be translated into modern notation or knowledge questions are to be answered. This shows the book's origins in university teaching, where musicology students had to master this material in one (!) semester. The tasks set are announced as a "digital course", but these are simply outsourced text tasks in pdf format, although something completely different would have been possible here. It is also strange that the book uses an awkward transcription with pseudo-historical musical notation from the so-called Munich School, which will hopefully not spread thanks to Schmid's knowledge of notation.

As I said, apples or pears: if you want to gain an insight into the development of our musical notation with a manageable amount of effort, you should read Schmid's book. But if you want to gain a more detailed knowledge of music recorded in original notation, we recommend Paulsmeier's course.

Manfred Hermann Schmid, Notationskunde. Schrift und Komposition 900-1900, Kassel etc.: Bärenreiter 2012 (Bärenreiter Studienbücher Musik 18)

Karin Paulsmeier, Notationskunde 17. und 18. Jahrhundert, Basel: Schwabe 2012 (Schola Cantorum Basiliensis Scripta 2)