50 piano sonatas by Leopold Koželuch

Characteristics, style and meaning explained using two sonatas.

Even seven of the earliest manuscript sonatas that have survived and therefore cannot be dated - in volume IV of the new edition no. 44-50, probably before 1773 - are clearly not intended for harpsichord, but were written for the "fortepiano", which was on the rise at the time. They can compete with early Haydn sonatas in terms of inventiveness and depth of emotion. One of them in E flat major, No. 47, still has a two-part sonata form (without development) in the first movement, Adagio, as in Mozart's E flat major Sonata K. 282. Mozart probably composed it at the beginning of 1775 in Munich during the premiere of the dramma giocoso ordered there La finta giardiniera and the influence of Koželuch can probably be ruled out. This is a remnant of the early classical period.

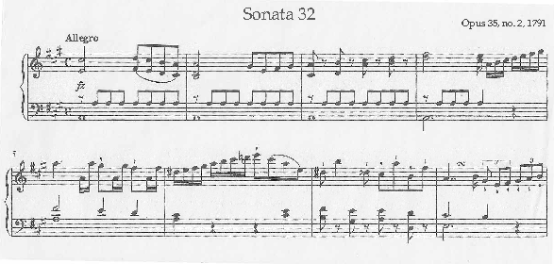

Two mature, large sonatas from the middle creative period deserve to be described in more detail. The one in A major op. 35 no. 2 from 1791 is in three movements and, like most, consists of a sonata form, a composite song form and a rondo form. The Music example 1 shows the prelude to the main theme in the form of the period; the postlude is extended to 12 bars.

After the gradual transition to the dominant key, the dominant seventh chord remains for four bars. Here (Music example 2) at bar 35 could therefore be the beginning of the secondary movement. Surprisingly, the opening motif of the main theme appears in E minor instead of E major.

The Music example 3 in bar 49 shows a fallacy and the augmented sixth chord to the dominant and in the prelude to bar 53 the beginning of the relatively short (26 bars) secondary movement. In any case, we can only speak of a "final group", which is often bandied about in some form studies, in Beethoven's music. In the development section, the composer uses a wide range of motifs from the main movement. Four complete bars of the opening in D major could mislead the listener into hearing a reprise beginning.

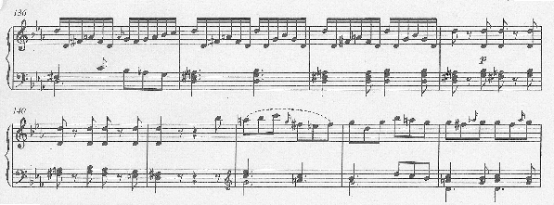

In bars 111-117, the two-part complementary guidance of the right hand (Note example 4).

Instead of preparing the recapitulation with a longer pause on the dominant, Koželuch uses a much more drastic means, namely a one-bar general pause. We leave the remarkable comparison between exposition and recapitulation with shortened main movement and lengthened subordinate clause and numerous differences in detail to the intuition of an inclined reader, should they obtain the notes. It is worth it!

The end of this movement deserves a small comment: Here the repeat signs, which were otherwise common in early classical and mostly in classical sonatas for repeating the development and recapitulation, are also missing in Mozart. Koželuch breaks with this tradition here and in all subsequent piano sonatas. We will come back to this. - It will be easier to describe the remaining two movements, both with a miniature section in the middle and both of sparkling ingenuity. The expressive Adagio is revealed when the precisely written ornaments (called "arbitrary changes" in the 18th century as opposed to "essential manners") are recognized as such. The Rondo offers much more than simply a finale. Its main theme - or let's say more expertly: - its refrain only appears three times, the second time very abbreviated, but also as the framework of the Minore and therefore never seems trite. Because the Allegro of the first movement at times approaches an allebreve meter and the Allegro of the rondo is notated in two-four time, the former should be taken briskly and the latter somewhat more slowly. The audience will be amazed at the dazzling virtuosity of the performance, even if the level of difficulty is quite accessible to a skilled amateur (around level 8-9 according to Klaus Wolters) due to the piano practitioner's hand-crafted notation.

Five sonatas in the first two volumes and six in volumes III and IV begin with a movement in a minor key. As with Mozart, this is a small minority, but one that deserves special attention. Koželuch experiments with polyphonic elements in them, for example at the beginning of the Sonata op. 26 no. 2 in A minor from 1788 (Note example 5).

The secondary movement begins quite normally with a twelve-bar theme in the parallel key of C major. But when the same theme appears in E flat major without any modulation after a general pause of almost two bars, the surprise is perfect. Schubert sends his regards. Incidentally, the general pause requires a brisk allegro tempo.

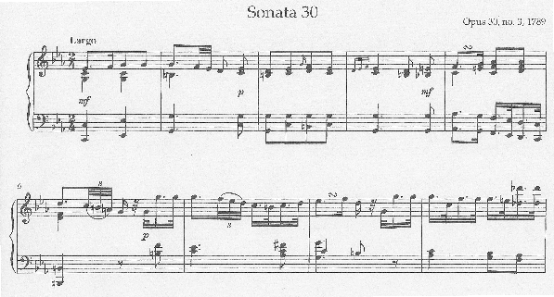

The Sonata op. 30 no. 3 in C minor from 1789 is even more interesting, also in its unusual sequence of movements. It begins with an extensive slow movement section, far too extensive for an introduction, even if it remains unfinished on the dominant.

The first 8 bars (Note example 6) look like the prelude to a period. The dotted semiquavers with thirty-second notes evoke a funeral march.

Attacca begins the Allegro in sonata form. Here too, the beginning, i.e. the main movement theme (Note example 7) a preceding movement. It is extended to 14 bars by repeating the half-finale. Instead of a final movement, there is a transition section to the major parallel with only 16 bars. The secondary movement (Note example 8) is extremely short at 36 bars compared to other sonatas by Koželuch and his contemporaries.

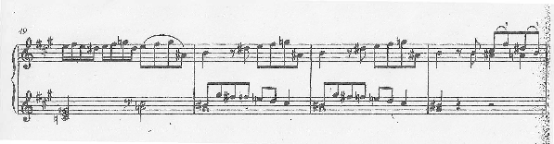

As usual, the repeat sign appears at the end of the exposition. But where should the repeat begin, with the Largo or the Allegro? The composer does not specify this, because it goes without saying: with the Allegro! The development section would again be very short at 32 bars. But does the recapitulation really begin here in bar 142, in the key of G minor? No, as in the A major sonata, it is a mock recapitulation. (Note example 9).

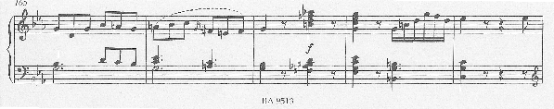

The "correction" to C minor (Note example 10). Schubert goes much further: in the two piano sonatas in A minor and C major ("Reliquie"), written almost simultaneously, he deliberately completely obscures the beginning of the recapitulation, which music theorists may well argue about. With Schubert, it is a departure for new shores. Should we allow Koželuch to do the same on a more modest scale?

Koželuch breaks with another tradition already mentioned above at the end of the recapitulation, namely the repetition of the development section plus recapitulation. This would not be possible because the Allegro and the Largo which concludes the movement are inextricably linked. This can be seen particularly clearly on the facsimile page of the first edition reproduced in the Bärenreiter edition, i.e. the only source: there is no double bar line, only the new bar mark 2/4. But even without the facsimile page, the interlocking is clearly evident: the opening chord of the Largo forms the conclusion of the cadenza at the end of the Allegro. This raises the question of whether Koželuch was inspired by this C minor sonata, which was composed two years before the A major sonata discussed above, to reconsider the second repetition of a sonata form. This is a hotly disputed question in performance practice. Mozart dispenses with the second repeat in sonata forms, albeit rarely.

Let's digress for a moment: in Mozart's piano sonatas, this only applies to his last two, K. 570 in B flat major and 576 in D major. However, the source situation for the B flat major sonata is unfavorable, but the case is clear. There is only one sonata for piano and violin: K. 481 in E flat major, none of the piano trios and one of the string quartets: K. 575 in D major. This means that Mozart used them deliberately. So they can actually be played where Mozart wrote them. Unfortunately, however, they are rarely heard in piano and chamber music recitals or on recordings, even by prominent performers. Koželuch, in contrast to Mozart, consistently stuck to this decision until the end of his life.

The second movement of the two-movement sonata begins attacca again, a rondo in liberating C major. The refrain appears once in G major in a strongly altered form and once in C minor as a brief reminder of the first movement.

All in all, Koželuch's work is not only worthwhile for pianists, but also as an interesting collection of examples for the subject of form theory, namely the subject that unites all other subjects of so-called music theory and is suitable for bridging the gap between theory and interpretation practice.