Share music: open compositions by Max E. Keller

Some of Max E. Keller's early pieces are suitable examples of open compositions for co-creating musicians. The Danish musicologist Carl Bergstrøm-Nielsen shows their structures, notation and compositions and identifies references to later works.

New music after the Second World War was initially composed in detail, at least here in Europe. However, it did not take long for various forms of openness to appear in performance. Stockhausen's development is a vivid example of this and offers a whole catalog of procedures: Time mass from 1956 operates with "degrees of blurriness" in the tempo. Piano piece XI from 1958 consists of many small sections that have to be played in an undefined sequence, and their content is also variable according to the last section played.

In the late sixties, openness became radical: Procession from 1967 and a number of other works used a simple notation consisting of plus and minus signs. It stood for up to four freely chosen, but consistently implemented, simultaneous parameter changes. Finally, the two collections consisted of From the Seven Days and For times to come (published in 1968 and 1976) mainly consist of texts. Verbal means can describe or paraphrase material, define traditional formal sequences or individual, cyclical formulas and much more.

Anyone who wants to argue that there were plenty of such experiments at the time, but that they remained a curiosity of history without much practical significance, is mistaken. Although the sixties and seventies can be seen as a "golden age" for this, further-reaching consequences only gradually emerged, beyond the sensational and fashionable. (1 Notes see below) Some composers made a specialty of it. John Zorn, for example, became a cult figure in the 1980s with his Game Pieces, Cobra in particular. They were created against the backdrop of Christian Wolff's compositions, which relied on interaction between the players, among other things. (2) The overall picture of currents became more complex. (3)

Although improvisational performance practice is not common in New Music everywhere, ensembles such as the Berlin Splitter Orchester (4)Zeitkratzer or the Ensemble Modern. The references to this article already indicate that something has happened since then, both in terms of composition and research. The musical examples from a total of 165 authors in the book Notations 21 were even mostly created in the new millennium. (5) More recent reviews are Nonnenmann (2010) on Mathias Spahlinger's Double affirmative, and Neuner (2013).

Improvisation has spread as an experimental practice alongside composition. On the one hand, this applies to concert life: An even stormy debate took place in Switzerland in 2010. (6) On the other hand, improvisation is now also being implemented in music academies. (7) So the whole intermediate area of exercises, agreements and concepts is also of renewed interest. Or let's put it more simply: open composition. After all, it is about the use of compositional processes in a new context of performance practice. (8) What is new about the historical situation, now, 60 years after Stockhausen's Time massIt could be that the integration of improvisation and composition has become more common. The composer is no longer the lone genius. Teamwork, a certain collective reasoning and action, has become more natural, as it is everywhere in society.

Recently in MusicLyrics an article about the compositions of Max Eugen Keller was published. (9) However, the early compositions for improvisers were not dealt with there. The present article can therefore be read as a supplement or simply as a presentation of examples of open compositions, primarily from the period around 1970. Keller's work contains a wealth of structures, notation and compositions, as I will try to explain below. In the following, I will only reproduce the score and refer to some more - the complete versions with all the explanations can be read on the IIMA website: http://intuitivemusic.dk/iima/mk.htm

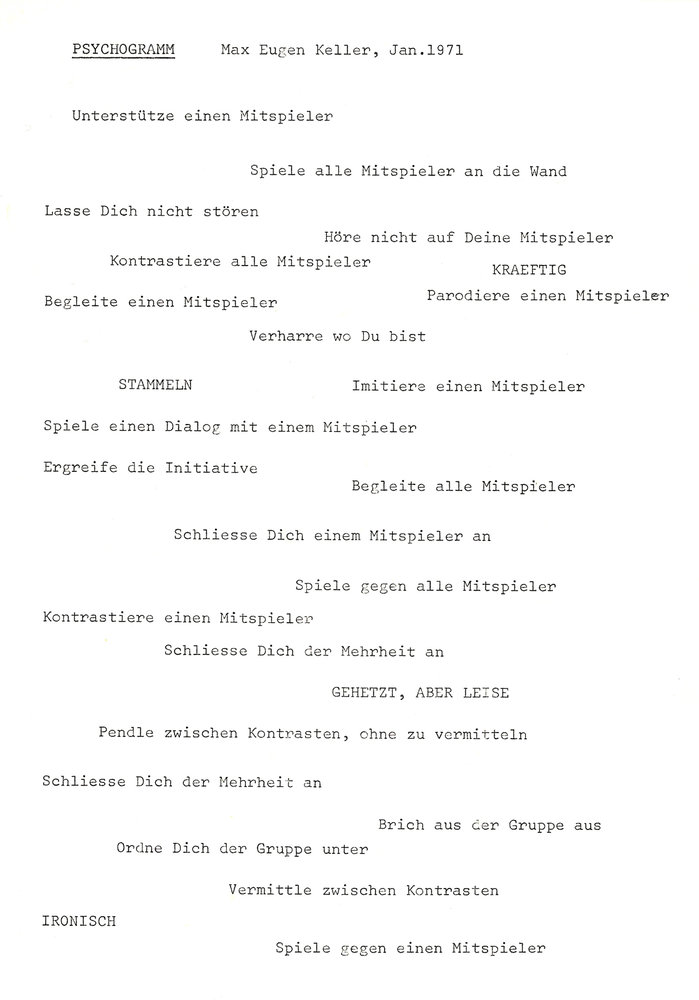

Psychogram

During the game, the performer should switch freely between the 22 behaviors described. The 4 capitalized words indicate starting points that can be useful for the beginning, for example. In large formal terms, we are dealing here with an aleatoric, kaleidoscopic progression. (10) There is a finite number of elements that are used by everyone, independently of each other and in an unpredictable order. However, elements are likely to recur frequently.

Many instructions describe musical behavior, but do not specify anything concrete in terms of sound, but rather describe relationships. They are often opposed to other musicians, but many also describe subordination. A few are in a quasi-neutral middle range, such as "mediating between contrasts".

The aesthetic focus is on conflicts and contrasts, the forms of which are systematically permitted and explored in music. The element "oscillate between contrasts without mediating" can be emblematic of this. The conventional practice of melody and accompaniment is not abolished, but it is given the possibility of contrasting. This can be described as a rediscovery of polyphony. Historically, it has been displaced by harmonic thinking in terms of chords, melody and bass. A term like "imitation" points to forms of human communication. Emotionality also inevitably comes into play here, compare the title of the piece. But it is not about the lonely, expressionist individual: Affect is reinterpreted as social.

The 22 elements can be categorized in a continuum or, rather, in several, depending on the interpretation. This could be a continuum between self-assertion and subordination, between opposition and alignment or something else. Thinking in continua was historically a discovery of the serialists. Just as melodies rearranged scale tones, this principle could also be used in other dimensions. This applies, for example, in Song of the youths by Stockhausen for the sound that moves along an imaginary line, a continuum, between electronic sounds and boys' voices, seemingly quite casually and "freely". The method thus serves to differentiate and integrate the material.

A further instruction in the explanations for Psychogramwhich also contributes to differentiation, stipulates that the players may make continuous transitions or jumps between the elements.

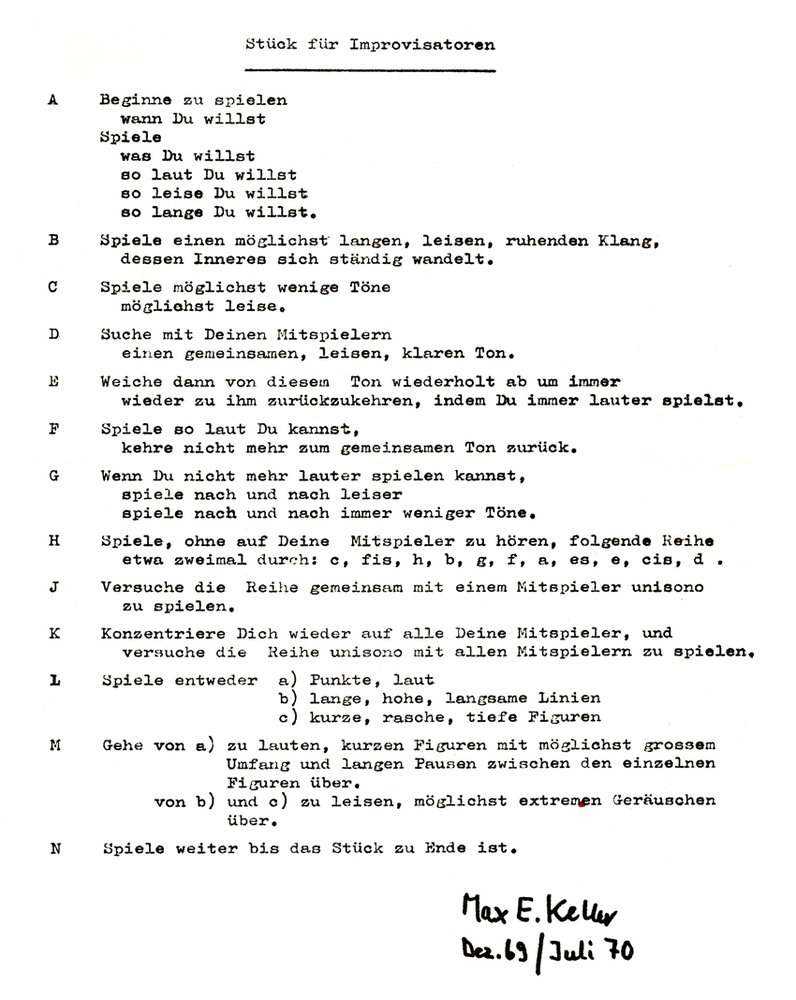

Piece for improvisers

The large-scale form here is not aleatoric, but sequential and arch-like. After the free play, further sections with different material are defined first, 13 in total. The process reaches a maximum of detailed binding in K and then ends in N in "free" play again.

The process is based on heterophony: this means that everyone plays the same sequence, but each in their own form and at their own tempo, so that the transitions are fluid. It is strategic that the sections are clearly different. Coordination is only possible through audible feedback between the musicians.

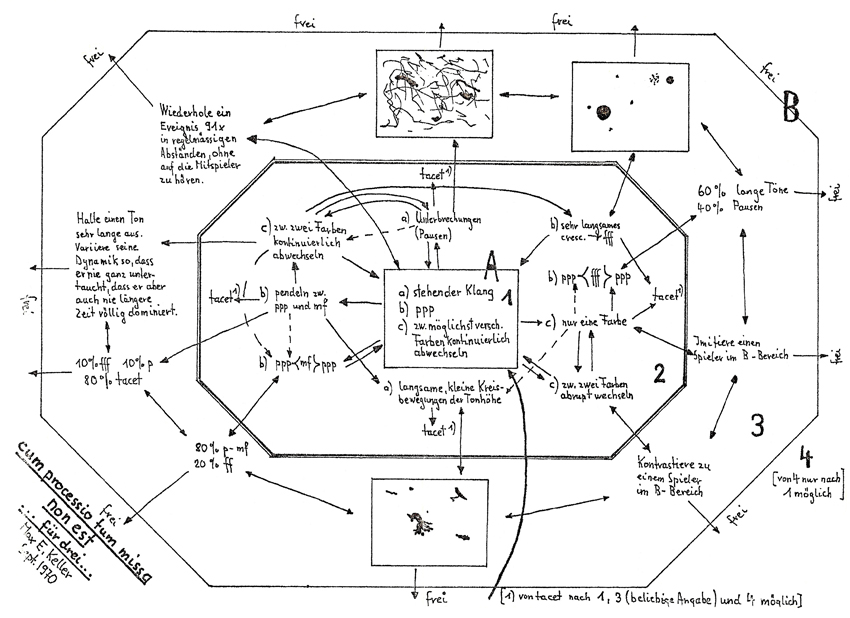

cum processio tum missa non est...

The large form develops from a mixture that is initially recognizable as relatively uniform, called "thematic structure" (the innermost zone with a), b) and c)). The development is initially subject to rules that ensure unity in the transition from one zone to the next, which is why new rules are introduced in zones 2 and 3. Only the last stage, zone 4, is completely ad libitum. The process becomes increasingly differentiated or labyrinthine. An arc-like or cyclical-formulaic return to previously played material is also possible, following certain rules and the arrows.

Heterophony is again a structurally supporting principle here (= everyone moves in a similar way with variations). However, it is also overlaid by the labyrinthine, which results from the use of different, aleatoric elements (= all can contrast each other in the later stages). After all, the aleatoric elements within their three categories are clearly similar to each other in the first two zones, so that a variation of what is already there rather than a complete contrast is created in advance.

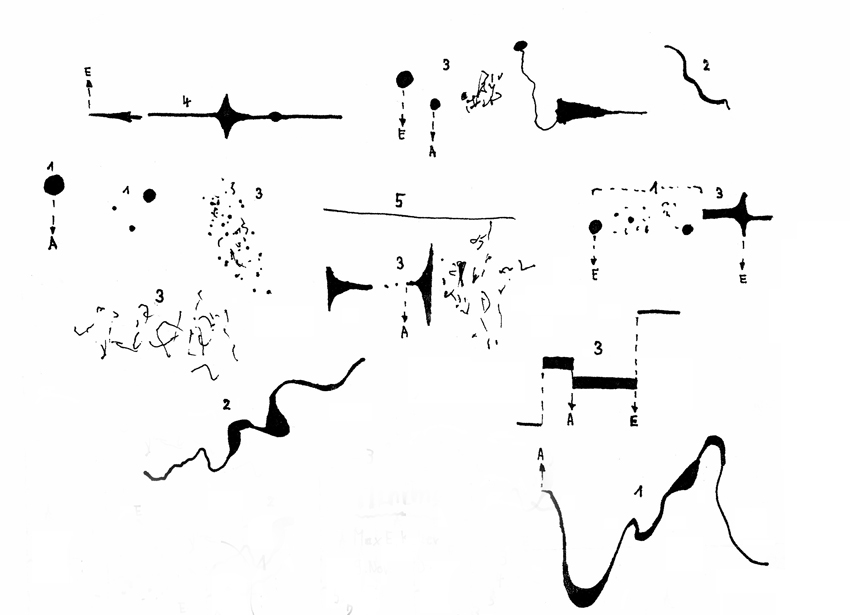

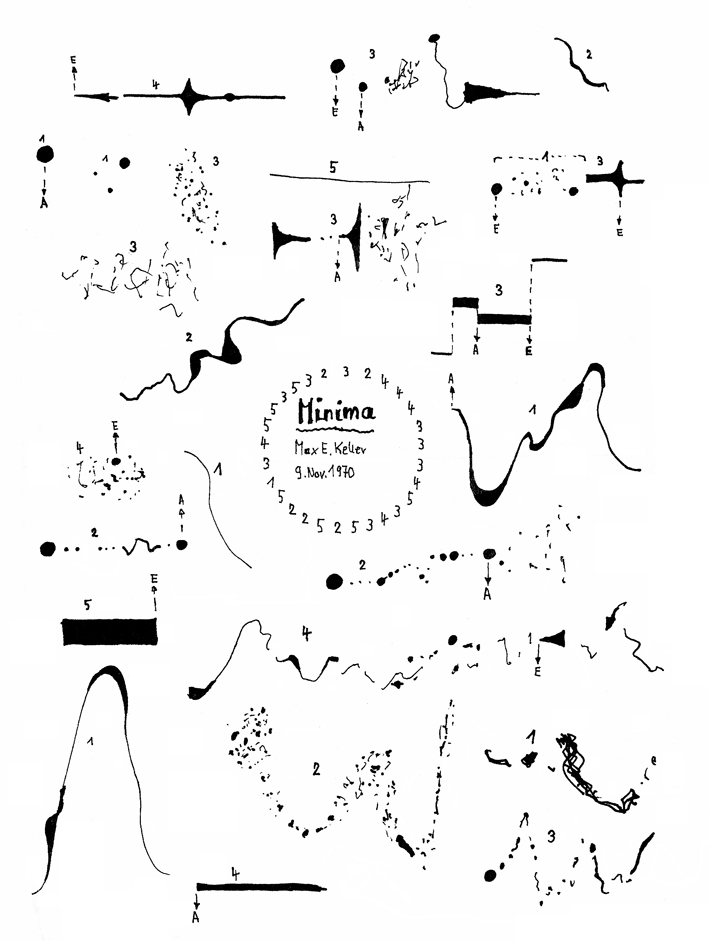

Minima

As in Psychogram the players switch individually between elements, which in this piece are freely notated graphically. However, the numbers above the elements indicate the duration: 1 = as short as possible, 5 = as long as possible. The idea of continuity is also at work here and prevents the elements from being given a standardized length. A similar variation in the length of the pauses is also provided: after each element, the player makes a pause, the length of which is taken from the circle. The numbers in it are interpreted in the same way as before. "A" and "E" are aimed at coinciding with the beginning or end of other players' elements, if "reasonably unconstrained". In addition, the general rule is: "The tonal result should be very thin, transparent music".

Minima is relatively uniform in sound and thus contrasts with the other pieces. But variation in the polyphonic density is strategically very important. By systematically varying the lengths of elements and rests, the composer ensures that not everyone plays at the same time and that rests occur so often and in such a varied way that the number of active players varies constantly. It can also be expected that different constellations of players will occur even with the same density, which also contributes to the variation.

Summarizing and perspective remarks

Compositional analysis and elaboration

This small selection of four pieces encompasses extremes of sonically vehement interactions in Psychogram to the thin, transparent sounds from the reductionism of Minima. On the other hand Piece for improvisers and cum processio ... rather eclectic in its material. Human forms of interaction, changing stages that are traversed by all players in a "caravan-like" manner, labyrinthine processes and sensitive variation in polyphonic density are selected compositional aspects. The pieces are not fully composed in the sense of being detailed on a micro level - but in the sense that they are based on ideas that were evaluated compositionally and then systematically worked out. The 22 interaction elements in Psychogram and the 27 graphic elements in Minima are, after all, examples of a level of detail that is largely sufficient to clearly suggest a wealth of possibilities.

Notation and how it co-defines the form

Text plays a major role in the notation of this selection. Verbal means can be used to describe certain sounds, even those that lie beyond the twelve tones, e.g: "Between two colors continuously alternate." But one can also describe relations between sounds or between musicians, as is so prominently the case in Psychogram was. They could hardly have been defined in any other way than with words. And with notes, it would have been possible to imitate emotions and reactions - but at the cost of liveliness.

Free graphics are also important in two pieces (Minima and cum processio). I understand free graphics here in contrast to formalized sign systems. Think of Stockhausen's plus-minus notation, for example, in terms of formalization. (11) However, it is also relevant to note here that the layout itself is an important means of formalization. The simple, linear sequence in Piece by ... the equal, aleatoric elements in the Psychogram and Minima and at the same time the concentric structure in cum processio compared.

Detailed or concise template

Because these four pieces presuppose further development through improvisational participation on the part of the musicians, they are short and concise, easy to read and survey - regardless of whether they are to be called "concepts" or "open compositions". (12) If a version that has been worked out in every detail is no longer required, then the work can become, as the French composer Jean-Yves Bosseur puts it, "a strong organism, with its full potential". (13) According to this train of thought, a version worked out in every detail would offer "less", less diversity of possible versions. (14) The Austrian composer Christoph Herndler (2011) is completely in line with this: when it comes to the written form, his aim is "not only to record the music, but also to communicate it".

Concept of material and historical performance practice

Performance practice is also changing historically in our time. (15) From the perspective of the broad lines, this cannot be viewed in isolation from the concept of material in New Music. Using a term coined by Levaillant (1996), we fundamentally start from "raw sound material" (Le fait sonore brût), both in early serialism and in free improvisation. Not only the tonal limitations of musical notation, but also the desirability of being able to freely define the entities with which one composes in all respects, call for a search for solutions beyond the compromises of traditional notation. Not to mention certain interesting human experiences. (16)

The authority of old theorists such as Dahlhaus and Adorno, for whom delegation on the part of the composer meant nothing other than a lack of responsibility, is gradually fading. Kopp (2010) touches on the historical dimension by still arguing against the two authors mentioned. Jahn (2006), on the other hand, is in favor of traditional writing. He develops an independent thesis by arguing against too much "free space" in compositions on a psychological basis. He illustrates his view using the metaphor of a guardrail on the highway - the guardrail represents what is notated, the music itself is everything that is not notated. I have never quite understood why the very regulated driving on the highway can become such a high ideal for aesthetic striving, but to each his own!

The importance of interaction and the consequences for the concepts of form

Psychogram shows an original use of interaction as compositional material. The piece is an early example of a systematic elaboration of differentiated interactive roles - interestingly before the publication of Vinko Globokar's article on Reacting (17)who describes very similar roles. See also the article by Keller himself (1973) on the importance of social processes and experiences of community, also on the part of the listeners.

In general, as indicated above in the discussion of this piece, polyphony, and a more direct, rediscovered one at that, is relevant to improvisational performance practice. It is obvious that the strictly homophonic is dependent on an external coordination. Heterophonic techniques are obvious - in Piece for improvisers this principle generates both vertical and horizontal diversity in the transitions to new sections and also places characterized by consensus, due to the caravan-like layout. The composer can define linear progressions in a coarser or finer outline, but because the interactive process tends easily towards unforeseen developments, aleatoric can take on a new significance, namely for the form. It provides in Psychogram and Minima for the musician to have a constant freedom of choice. Here we are far removed from the finely chopped, swirling structures of Penderecki and other Polish composers, which take place on a detailed level. There is still a lot of research to be done into how musicians can influence or determine the course of form through their choices in playing.

Conclusion

Keller's four pieces make use of a considerable range of compositional methods and techniques: in-depth analysis of the material, aleatoricism in relation to form, polyphony, heterophony, sequential form, labyrinth form, relations as musical material, non-established forms of notation. They contribute to combining conventional composition with a still relatively new form of performance practice. Interaction influences the form of collaboration. Concise notations are used which communicate the composer's idea directly and thus require a minimum of analytical deciphering - both for musicians and for interested listeners.

Appendix: Later open works by Keller

Music is produced differently within different traditions. By far the most widely performed classical music today is performed without the need for improvisational skills. But it does require advanced technical skill and an effective production method. Sight-reading is important, so that rehearsal time can be reduced to a minimum. Many composers draw the conclusion that they should also use a mainly traditional script for new music so as not to block their access to the audience. For Keller, texts and messages with political content were also important. (18)

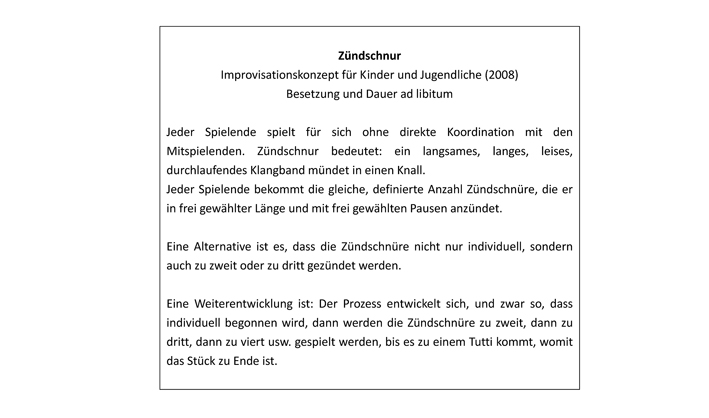

Pedagogy is less about effective cultural production and more about immersing yourself in content and getting to know it. We can call this a different method and describe it as "workshop-like". The musicians gradually discover or even develop the field and co-determine the outcome. In 5 Improvisation models for young people (1995) (19) and in the eponymous 5 Improvisation models for young people (2008), there are structures that are similar to the early compositions, but simpler. There are also conventional, linear and simple scores. However, an example now follows, Fuse from the later collection, which exemplifies heterophonic and formulaic structures. This time the notation is exclusively verbal:

The workshop-like method is widespread among ensembles that have the freedom to create their own work. The early pieces analyzed above were created in the environment of the Gruppe für Musik founded by Keller. At that time, he also worked improvisationally with Gerhard Stäbler and Wah Schulz.

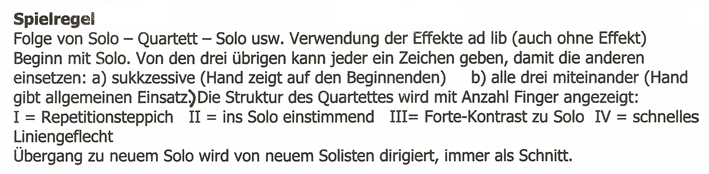

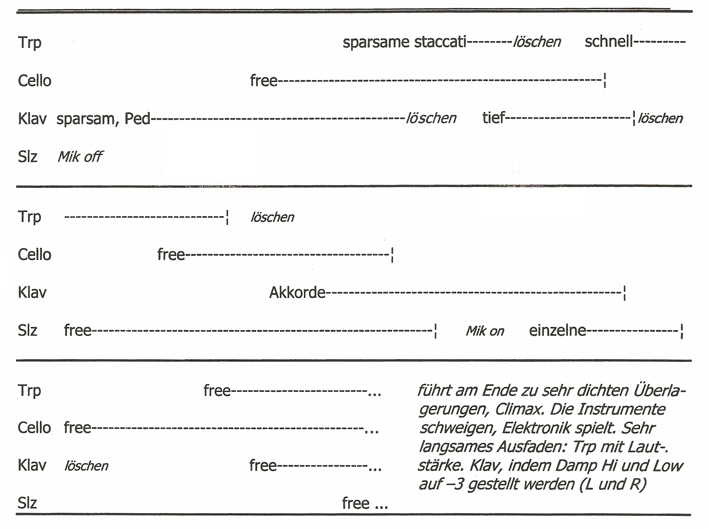

Some improvisation concepts date from 2003, written for a group with Stefan Wyler (trp), Alfred Zimmerlin (vcl) and Dani Schaffner (perc). Keller himself played piano and synthesizer. Electronic sound conversion could be used in all of them. The compositions belong in a "gray area". They are formulated only for the musicians concerned and do not have the full explanations that were characteristic of the pieces analyzed above. However, they can be examples of how compositions can be quickly realized among themselves, with keywords and little effort. Apart from playing instructions, these concepts contain a great deal of technical information on setting up the apparatus. Generalizing these would certainly have been a special task; another, perhaps somewhat less difficult one would be to abstract from the specific instruments. For example, could "cello" be replaced by another string instrument or by any other instrument? In their specific context, however, such questions need not be answered at all.

From In metal here is a playing rule based on the interaction of the musicians and integrating experiences from the nineties with "conducted improvisation":

From Without end an excerpt from the score - for outsiders, the keywords would probably seem rather abstract. It is also conceivable that "free" implies a certain degree of agreement among the musicians, especially if the pieces had been rehearsed beforehand. At the very least, it can be assumed that they were somewhat familiar with each other's playing styles.

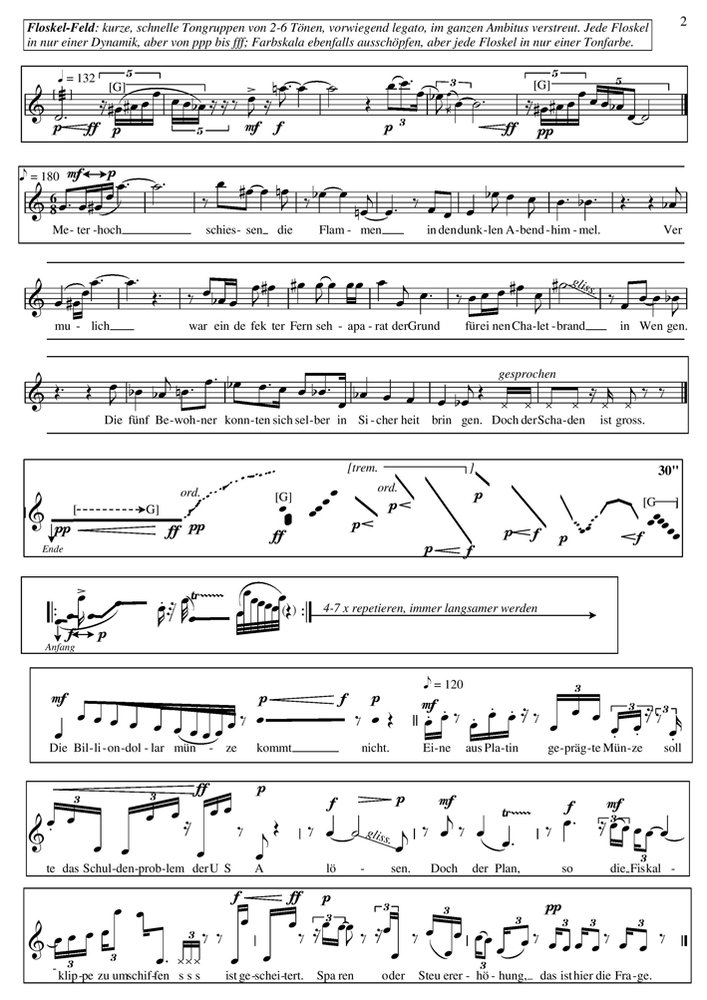

Improvisation and experimental performance practice appear in a work with politically oriented texts from recent times, namely Mobile for 1-5 instruments ad libitum from 2013.

The elements in the boxes can be freely combined. However, the "phrase box" should be used at the beginning and at least twice in the course of the piece. Texts can be performed in different ways according to the instructions. Together with the instrumental elements, we really have a collage here: sentences can be stacked chaotically on top of each other. They deal with serious problems, which are in no way related to each other, but rather are abruptly juxtaposed. The highly differentiated playing is just as abruptly juxtaposed with the prominent "empty phrases". However, the piece accommodates sight-reading in that the pitches and rhythms are composed in detail. At the same time, [G] means that the sound can be noisy. Again, diplomatically for the classically trained musicians, this can be omitted.

Keller's open compositions since 1970/71 build on discoveries that were explored in depth in early pieces: expanded material, descriptive notation, interaction as an essential dimension, creative collaboration. However, original pedagogical works and an informal compositional approach also become visible. And an example of bridging the gap between the otherwise separate working methods of sight-reading or workshop.

Carl Bergstrøm-Nielsen is a Danish composer, improviser and music researcher.

Website: www.intuitivemusic.dk

Notes

1

As far as consequences outside of concert life are concerned, we can only briefly mention here that music education was redesigned and that the newer music therapy was created as a specialist discipline.

2

See Bergstrøm-Nielsen (2002ff), special categories on Wolff and Zorn G2.5 and G2.3 (both old and new sections), also Gronemeyer et al (1998). Vitkova (2005) attests that Wolff composed in this way not only in the 1960s, but also later, e.g. in For John (2007).

3

Polaschegg (2007) and (2013) contain detailed signal elements of this.

4

Reimann (2013)

5

Sour (2009)

6

The article by Meyer (2010) seemed to be the catalyst for this explosion. The discussion continued in Dissonance (2010) and Kunkel (2010) with more than 35 participants. Subsequently, Nanz (2011) was published. - Meyer (2007) previously reported lively discussions on improvisation issues.

7

In Lucerne, you can obtain a Bachelor of Arts in Music with a focus on improvisation. Mäder et al (2013) contains documentation and didactic and content-related reflections. Jeremy Cox, director of the Association Européenne des Conservatoires, estimated that 90% of the approximately 200 members have introduced improvisation lessons. See Cox (2012). Other important places where free improvisation is taught include Ghent, Belgium; The Hague, Holland; Oslo, Norway.

8

See the discussion in Mäder et al (2013) p.38f.

9

Amzoll (2015)

10

Aleatoric, from the Latin alea = cube, means random, but within a defined framework.

11

See Müller (1997)

12

A discussion of these terms can be found at the end of the article Bergstrøm-Nielsen (2002).

13

Bosseur (1997), translation by the author

14

As a composer, I can also personally confirm that it can be a great pleasure to hear completely different versions of the same work. Interpretations can even change over the decades.

15

Müller (1994) argues that for the analysis of indeterminate music (which in his view also includes Stockhausen's Procession) the sole consideration of method on the part of the composer and of reception is not sufficient. If the composer shares the creative work with a performer, then the performance practice as such must be examined. Kopp (2010) follows a similar line of thought.

16

Ochs (2000) points out the advantages of creative collaboration: "... the decision to use (structured) improvisation ... to create the possibility of even more ... than the composer imagined possible ... Or, at the very least, to allow for the possibility of different or fresh realizations ... with each performance" (p.326).

17

Globokar (1970)

18

See Amzoll (2015) for a more general orientation on Keller's work

19

A selection of these is published in Nimczik/Rüdiger (1997).

References

Amzoll, Stefan (2015):

Color journeys. The Swiss composer and improviser Max E. Keller. MusikTexte 147, November.

Bergstrøm-Nielsen (2002):

Open composition and other arts. ring talk about group improvisation, June. Online: www.intuitivemusic.dk/iima/ - see Bergstroem-Nielsen.

Bergstrøm-Nielsen, Carl (2002ff):

Experimental improvisation practise and notation.

An annotated bibliography. With addenda. Online: www.intuitivemusic.dk/iima/ - see Bergstroem-Nielsen.

Bosseur, Jean-Yves (1997):

Le Temps de le Prendre. Paris (Editions Kimé).

Cox, Jeremy (2012):

Oral communication during the lecture QUO IMUS?: a "premeditated improvisation" on ideas stimulated by the Symposium and their implications for European music academies. Symposium Quo vadis, devil's violinist?University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna, January 28, 2012.

Dissonance (2010):

Replies to Thomas Meyer's article "Is free improvisation at an end? (dissonance 111) Online: http://www.dissonance.ch/de/rubriken/6/95

Globokar, Vinko (1970):

"Réagir", musique en jeu 1, 1970 German version in Melos 1971,2 (without music examples). Online: http://intuitivemusic.dk/iima/ - see Globokar.

Gronemeyer, Gisela; Oehlschlägel, Reinhard (1998):

Christian Wolff. Cues. Writings and Conversations / Cues. Writings and Conversations, in: Edition MusicLyrics 005.

Herndler, Christoph (2011):

Waymarks when noting unforeseeable events, in: "31" - The magazine of the Institute for Theory, No. 16/17, p. 126 ff. ISSN 1660-2609 (Switzerland).

Jahn, Hans-Peter (2006):

On the quality of memory loss. The shackles of notation, MusicLyrics 109, May.

Keller, Max E (1973):

Improvisation and commitment, Melos 4.

Kopp, Jan (2010):

The sense of action in writing. The experience of the musician as an object of composition. MusicLyrics 125, May, pp. 32-43.

Kunkel, Michael (ed.) et al (2010):

Discussion.... Dissonance, Swiss music magazine for research and creation 111, December, pp. 64-77. online: http://www.dissonance.ch/de/hauptartikel/82

Levaillant, Denis (1996):

L'Improvisation Musicale. (Biarritz, Editions Jean-Claude Lattès 1981). Part of a series: Musiques et Musiciens. New edition: Arles 1996

Meyer, Thomas (2010):

Is free improvisation at an end? Dissonance, Swiss music magazine for research and creation 111, September, p.4-9. Online: http://www.dissonance.ch/upload/pdf/diss111.hb_04_09.pdf

Mäder, Urban; Baumann, Christoph; Meyer, Thomas (2013):

Free improvisation - possibilities and limits of mediation. Series: Research report of the Lucerne School of Music 5th electronic document. Online: https://zenodo.org/record/31339/files/2013_5_Maeder-Baumann-Meyer.pdf

Müller, Hermann-Christoph (1994):

On the theory and practice of indeterminate music. Performance practice between experiment and improvisation. Regensburg (Gustav Bosse Verlag). Cologne contributions to music research (Niemöller, Klaus Wolfgang ed.) Volume 179.

Müller, Hermann-Christoph (1997):

plus minus equals. Karlheinz Stockhausen's "Procession", MusicLyrics 67/68, January.

Nanz, Dieter A. (ed.) (2011):

Aspects of free improvisation in music. Hofheim (Wolke Verlag).

Nanz, Dieter A. (2007):

Improvising and researching. Thoughts on the fringes of the Basel improv matinees. MusicLyrics 114, August, p.83-84.

Neuner, Florian (2013):

On the tip of the iceberg. The Berlin composer and publisher Juliane Klein. MusicLyrics 139, p.5-13, November.

Nimczik, Ortwin/Rüdiger, Wolfgang (1997):

Monophonic polyphony. Three improvisation models by Max E. Keller (1995), Music and education 1, January/February.

Nonnenmann, Rainer /(2010):

Against the loss of utopia. Mathias Spahlinger's "doubly affirmed" breaks new ground. MusicLyrics 124, February.

Vitková, Lucie (2015):

Learning to Change with the Music of Christian Wolff, in: Rothenberg, David (ed.): vs. interpretation. An Anthology on ImprovisationPrague (Agosto Foundation), p.51-62.

Ochs, Larry (2000):

Devices and Strategies for structured improvisation, in: Zorn, John (ed.): Musicians on music. New York (Granary Books/Hips Road). P. 325-335.

Polaschegg, Nina (2007):

Entanglements. Redefining the relationship between composition and improvisation, MusikTexte 114, August.

Polaschegg, Nina (2013):

Mutual fertilization and interpenetration. On the tension between composition and improvisation. MusicLyrics 139, November 2013.

Reimann, Christoph (2013):

Collective individual. The Berlin Splitter Orchestra. MusicLyrics, August, 29-35.

Sauer, Theresa (2009):

Notations 21, New York (Mark Batty Publishers). See also: https://notations21.wordpress.com/theresa-sauer

______________________________

Link to a performance by Minima on November 13, 2017 as part of the Copenhagen Openform Festival