Furrer's work in radio and his attitude towards the avant-garde

In her search for personalities who knew her father, the Swiss composer Walter Furrer (1902-1978), Beatrice Wolf-Furrer met with Klaus Cornell and Walter Kläy in the first trimester of 2016.

After the informative conversation I had with organist Heinz-Roland Schneeberger in Thun on December 5, 2015, I continued my search for people who still knew my father, the Swiss composer Walter Furrer (1902-1978). In the course of the last few months, I have come across two such people.

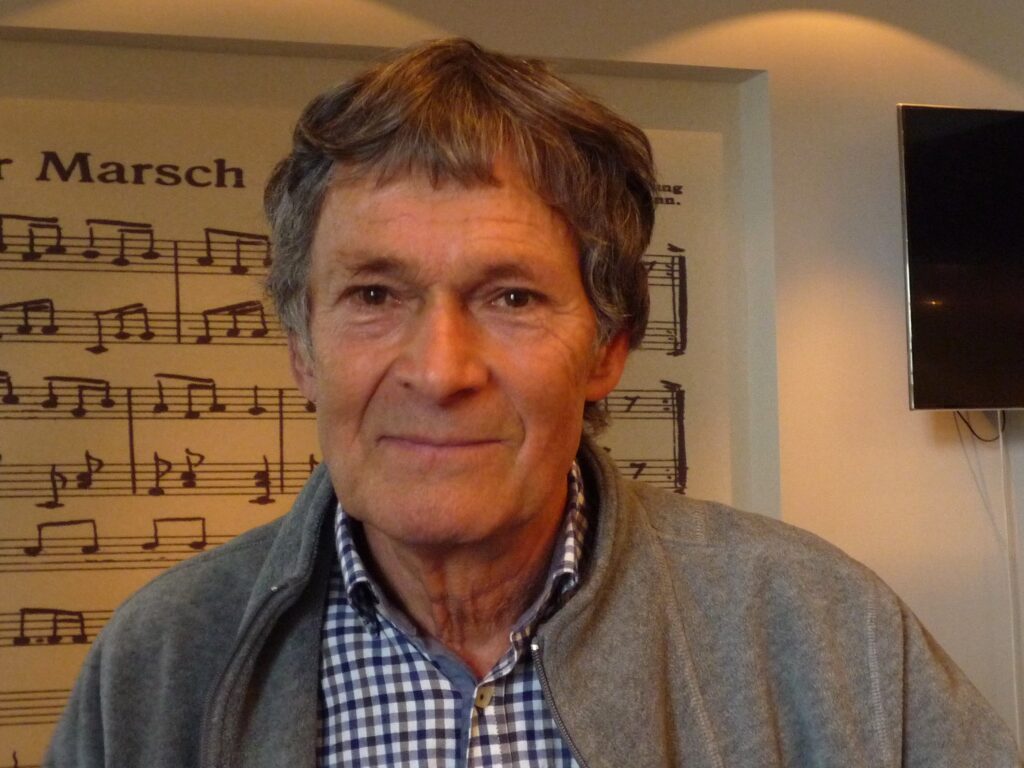

Klaus Cornell

During my research at the Burgerbibliothek Bern, which has been in charge of Walter Furrer's entire musical estate since June 2012, I kept coming across the name Klaus Cornell at intervals and remembered that my father had also mentioned him occasionally in conversation.

I didn't have to search for long: Not only did I find out via the homepage that Klaus Cornell has a stringent career as a conductor and composer and has been awarded a number of prizes, but also that he now lives in Constance. This is not to be taken for granted, as from 1989 to 2000 he was a successful musician in the state of Oregon (USA), where he would have been only too happy to stay. But in the end, the Bernese-born musician was drawn back to Switzerland, if not to neighboring countries. He chose Constance as his retirement home, a city that brought him closer to home but, as he emphasizes, "a little more space". I had the opportunity to talk to him there for about an hour on February 27, 2016.

In the 1960s, Walter Furrer and Klaus Cornell worked side by side in the same company. After twenty-five years as choirmaster and conductor at the Stadttheater Bern, Walter Furrer moved to Studio Radio Bern in 1957, where he worked for a good ten years as conductor, director of the chamber choir he founded on behalf of the station and composer.

In 1961, the young Klaus Cornell, who had already gained relevant professional experience in Switzerland and Germany, joined the station's team, where he held a managerial position until 1983.

He was already on the road as a composer in the 1960s, and his best-known work from this era is the 1965 radio opera Peter Schlemihl, picture book for musicwhose libretto Kurt Weibel adapted from Adelbert von Chamisso's novella Peter Schlemihl's wondrous story wrote.

When recording the Schlemihl the chamber choir conducted by Walter Furrer (see above) also took part. According to Klaus Cornell, he fondly remembers the collaboration with his older composer colleague, which also worked in the opposite direction. In 1965, for example, he was production manager for the entire recording of Furrer's commissioned composition Quatembernacht. A radio ballad based on a Valais legend for chamber orchestra, organ, soloists, choir, children's choir and speaking voices controlled. Kurt Weibel also acted as librettist in this case.

Both composers worked in the "radio play music" sector, which was particularly important for radio at the time.

Apart from the immediate professional collaboration, there were also technical discussions of a fundamental nature, for example about the congenial collaboration between librettist and composer, which is crucial for the success of an opera. The operetta genre - the so-called "light muse" was already experiencing severe hostility at the time, which, as is well known, ended with the banishment of this genre from subsidized theaters - was also the subject of fundamental discussions, whereby Walter Furrer, in view of the unbroken success of operetta, spoke out against its radical dismantling.

There was also a lot of talk about contemporary music production at the time. According to Cornell, Walter Furrer had "a critical relationship" with the contemporary music of the 1960s and 1970s - think of the prominent International Summer Courses for New Music organized by the Darmstadt International Music Institute (IMD). At first glance, this is surprising, because during his student days in Paris, Walter Furrer was in the camp of the avant-gardists, who were fiercely opposed in the 1920s, and was particularly committed to Arnold Schoenberg's music, which was by no means generally recognized at the time. He himself repeatedly resorted to serial techniques; however, as he was at the same time highly concerned with sound, his own modernity was, in my opinion, probably less ostentatious.

Walter Kläy

The resolution of this apparent contradiction came to me in a conversation with the Bernese musician, music theorist and music critic Walter Kläy, whose acquaintance Klaus Cornell had arranged for me and which took place in Bern on April 4, 2016. But first things first.

Walter Kläy first completed a practical music education (violin, bassoon, piano) and then, from 1973 to 1976, a theoretical one, which he completed with a theory teacher's diploma at the Bern Conservatory. Prior to this he worked (until 1973) at the Radio newspaper and as an editor in the foreign desk of the Swiss Dispatch Agency. In 1976, he joined Studio Radio Bern, where he worked as a music editor and also produced the highly acclaimed Late-night concerts at Studio Bernwhich were broadcast on Mondays.

Coincidentally, he worked in the same office as Walter Furrer and the conductor and pianist Luc Balmer, who worked as a versatile employee at Studio Bern at the time. Walter Kläy is co-author of the commemorative publication for Theo Hirsbrunner, which was published in 2011 under the title Dialogs and resonances/music history between cultures published by the Munich-based publisher edition text + kritik.

On September 7, 1970, Walter Kläy conducted an interview with Walter Furrer, which took place in his home in the Halensiedlung, in no. 40/1970 of the magazine radio + television and now became the central topic of our discussion. Walter Furrer had asked for a written answer to the questions, which was granted. The text of the interview contains many very precise formulations that provide important insights into the development of Furrer's oeuvre.

Furrer's three creative periods

Walter Furrer did not like to be analytical about his works, but here he made an exception. As the text reveals, he himself divided his compositional work into three periods. The first began in Paris in the 1920s, when he studied counterpoint with Nadia Boulanger and intensively studied the avant-garde composers of the time, Schönberg, Stravinsky, Roussel and Bartók.

The second was triggered by his work in the theater as a chorus master and conductor, in the sense that he was now deeply interested in "the dramatic side of music", as evidenced by the operas he wrote at the time. The faun and Dwarf nose and the ballet Path into life witnesses.

The third period was initiated by his engagement at Studio Radio Bern (from 1957) and represented a feedback to the first, "in that I made use of the knowledge of serial technique and the expansion of the linear and melodic, which simultaneously led to an expansion of the harmonic". As examples, he cites the fifth song of the cycle Five death dance songs for alto and piano after texts by Christian Morgenstern (1927), which begins with a twelve-tone row - "unconsciously, of course, but nevertheless as a reflection of my Schoenberg studies" - as well as the Psalm 142 for soprano and organwhich is "consciously worked in twelve-tone technique". However, this is "not immediately noticeable because all the other elements of the composition are assimilated into it".

Nevertheless, I think it would be wrong to see Walter Furrer as a sworn intellectual dodecaphonist. The "intellectualism associated with dodecaphony has nothing to do with my music", he emphasizes at the end of the interview. His most important concern was "always to write for the instruments, for the voices, even for the conductor. It is important to me that my performers enjoy the music ... This also allows me to reach the listener."

In this context, it is also mentioned how difficult it is for the compositional

avant-garde had in the 1920s - scandals at performances of avant-garde music were not uncommon, especially in Paris - and how easy it had it back in 1970 (and still has it today). "You can no longer compare today's avant-garde with the past," Walter Furrer says in the interview. "Today you put your hands under their feet, back then there was nothing to laugh about."

According to Walter Kläy, Walter Furrer appeared very serious, concentrated and, he was particularly struck by this, depressed during the interview. This can be explained by the truly depressing situation in which the ageing composer found himself at the time. Although his works had attracted a lot of attention and often warm applause, he had not achieved what one would call a real breakthrough. He also missed his work at the radio station, for which he only worked as a freelance conductor of the chamber choir. What's more, this highly artistic chamber choir - which had won third prize out of 59 participants at the Festival international de chant choral in Lille on October 10/11, 1962 - was already threatened with dissolution in 1970. All attempts to halt this development were in vain, and at the end of 1972 it disappeared from the scene for good.

I would like to thank Klaus Cornell and Walter Kläy very much for making these discussions possible.