Donaueschinger Musiktage: The compulsion to constantly reinvent oneself

One hundred years of the Donaueschingen Music Days: an attempt to take stock.

It was to be a big anniversary festival, not a celebration, but a broad-based showcase of today's music-making with a look into the future. Nevertheless, there were two small glimpses back: in the opening ceremony, the Diotima Quartet played Paul Hindemith's third string quartet, which was first heard on August 1, 1921, the year the festival was founded, in Prince von Fürstenberg's castle in Donaueschingen. And the Lucerne Festival Contemporary Orchestra, which was now performing in Donaueschingen for the first time, performed two world premieres by Christian Mason and Milica Djordjević under the direction of Baldur Brönnimann. Polyphony X by Pierre Boulez, which had caused an uproar in Donaueschingen in 1951 and then permanently disappeared into oblivion. The performance turned out without a hitch, and one wondered what had once seemed so scandalous about this harmless zombie. Perhaps the sterile serial mechanics?

Making music in front of and behind the fences

Otherwise, the festival program, which had been extended by one day, was full of the present. 27 world premieres in 24 concerts: that bordered on acoustic overkill. However, the events could also be followed à la carte on the screen at home, as everything was broadcast live on the radio and Internet by SWR. This created a public that reached beyond the notorious insider circles, and the "new music fences" were also cleared away for a short time on site. With the "landscape composition" with mass appeal Danube/Rauschen Daniel Ott and Enrico Stolzenburg created a Jekami event for over a hundred participants, from accordionists to brass bands, garnished with sounds and noises from loudspeakers. The venue: the Donaueschingen shopping mile on Saturday afternoon.

In the orchestral and ensemble concerts, the audience was once again among themselves and, alongside many new names, also encountered the usual suspects: Siemens Prize winner Rebecca Saunders, the tireless Enno Poppe, the trendy Chaya Czernowin and Beat Furrer, who came up with a compact orchestral piece. The finale was the oratorio, which poured out in broad waves of sound The Red Death by Francesco Filidei on a text by Edgar Allan Poe, the unrivaled Master of Disaster. It was a fitting end to a festival in which scepticism about the future and fantasies of doom have long been an undercurrent of cultural criticism, applauded with relish, and in which artistic unease is increasingly spreading amidst the saturation. In this respect, it is business as usual, even in the anniversary year.

The prince as patron of new music

A quick look at the old programs shows that there was never any question of aesthetic paralysis. It is one of the characteristics of the Donaueschingen Festival that, driven by the contradictions of the times, it had to reinvent itself time and again and thus inevitably look to the future. Even its foundation was actually a productive misunderstanding. Prince Max Egon II von Fürstenberg, an old-style nobleman loyal to the emperor, had the crazy idea of creating a stage for young composers in war-ravaged Germany at a time of revolutionary upheaval. For him, this was more of a patronizing whim; he loved hunting and glamorous parties. But for the composers and performers he attracted, the "Donaueschingen Chamber Music Performances for the Promotion of Contemporary Music", as they were called at the time, were a promise of the future.

-

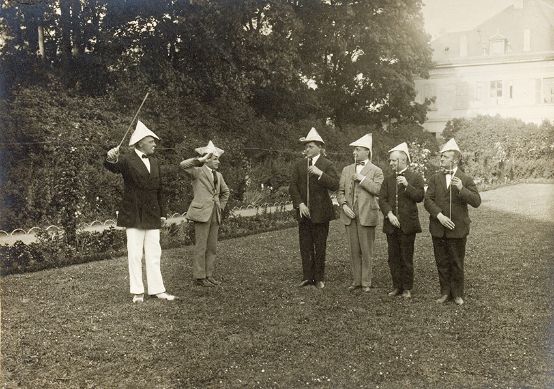

The Frankfurt Amar Quartet performed Paul Hindemith's military music parody "Minimax - Repertorium für Militärmusik" at the Donaueschingen Music Festival in 1923. On the left, the festival founder Prince Max Egon II zu Fürstenberg. Photo: Princely Fürstenberg Archive

A program committee consisting of the Reger student Joseph Haas, the pianist Eduard Erdmann and the Donaueschingen choirmaster and archivist Heinrich Burkhard had put together a program for three concerts from the submissions of one hundred and thirty-seven composers for the first year; an international honorary committee, which included Ferruccio Busoni, Richard Strauss, Franz Schreker and Arthur Nikisch, gave the undertaking the higher consecration. Among the composers from the very beginning were Philipp Jarnach, Alois Hába, Alban Berg, Paul Hindemith and Ernst Krenek, later joined by Schönberg and Webern. The honeymoon lasted six years, after which the prince's expenses became too high.

A festival on the move

In 1927, the festival moved to Baden-Baden. Now the conductor Hermann Scherchen took the reins, and with Teaching piece by Brecht/Hindemith (with audience participation), the Lindbergh flight by Brecht/Hindemith/Weill and film music by Hanns Eisler brought "applied music" to the fore. But even this did not last long, as the economic crisis of 1929 dealt the company a fatal blow.

So in 1930 they moved on to Berlin and in 1933, when the Nazi disaster set in, they returned home to Donaueschingen. In the meantime, the errant prince had joined the SA, and the new-born Donaueschingen Music Days now featured folk cantatas and community music with the Swabian Women's Singing Group. In 1938, Othmar Schoeck's Prelude for orchestra op. 48 on the program. With the outbreak of war in 1939, the spook came to a temporary end.

Risen from the ruins

The second big start came in 1946, initially with established names such as Prokofiev, Shostakovich and Hindemith. In 1950, Südwestfunk Baden-Baden joined in with music director Heinrich Strobel and conductor Hans Rosbaud, and within a few years Donaueschingen had developed into an international hotspot for contemporary music. Everything of note in the avant-garde now came and went here: the top dogs of serialism such as Stockhausen and Boulez, the aleatorics, the Polish sound composers, Cage, Berio, Ligeti, Xenakis, Kagel and many others. The principle of always offering a forum to new tendencies was also valid during the postmodern phase and has remained so to this day. But things are probably changing now.

From the very beginning, the Musiktage have gradually expanded their aesthetic horizons. In the first phase, it was still largely limited to the German-Austrian area. From 1946, it expanded to Europe, with a few detours to non-European regions. And from now on, the aim is to turn specifically to other cultures. The anniversary year has now set the signal for this.

The globalization of Donaueschingen

The step is right and necessary. New music" is no longer a European phenomenon. But the more it spreads across the globe, the more European standards are being called into question. Under the motto "Donaueschingen global", the program now included ensembles, composers and performers from Colombia, Bolivia, Ghana, Thailand and Uzbekistan, among others. While some South Americans still work at the intersection of indigenous cultures and European-American influences, most of the Asian and African contributions continue to develop their own traditions; their preferred means are electronics and current media forms of presentation.

The traditional festival-goer in Donaueschingen was confronted with completely new listening and viewing experiences. And with a bag full of questions: What is "new" about these contributions? Is it new in substance or just new for us white men and women? What is the relationship between the "new" and the "old" of the region of origin? Do we need to know this in order to understand it? Is it about intercultural understanding or just the good old exoticism show in new, colorful, media-spruced-up clothes? In any case, it was clear that there was a breath of fresh air in the Black Forest, and the thematic selection guaranteed that the sails of the anti-colonialist debate were also allowed to billow.

Donaueschingen global" was right on trend. How things will continue under the new director Lydia Rilling, who is now taking over from Björn Gottstein, remains to be seen. However, two neuralgic points are already recognizable: one concerns the limited time capacities of the weekend festival. With the new cosmopolitanism, the established white avant-garde and its audience could unexpectedly find themselves on the defensive. The other concerns the cooperation with government-related organizations at "Donaueschingen global". If the Musiktage continue to rely on their organizational and financial efficiency, then the hip multicultural fun can continue unabated. But in doing so, they also become dependent on foreign policy, which subordinates cultural exchange to its guidelines and uses it to cultivate its image. And then artistic freedom in new music will also come to an end.