A musical prince of the Renaissance

To mark the forthcoming 500th anniversary of Josquin Desprez's death, Roland Wächter, program manager of the Early Music Festival Zurich, talks to Max Nyffeler about the composer's life and work as well as the context in which he lived. During his lifetime, he was a European luminary. And what does he still have to say to us today?

Max Nyffeler: August 27 marks the 500th anniversary of Josquin Desprez's death, and now, in March, the Early Music Festival Zurich ea program focus. What considerations were you guided by?

Roland Wächter: Commemorative days always attract a lot of attention. It makes sense for an organizer to respond to this. It wouldn't necessarily have been necessary with Beethoven, everyone knows him. But with perhaps the greatest composer of the Renaissance, who is little known in today's musical world, it's a different matter.

How is this reflected in the program?

Of course, you can't run a festival program with Josquin's music alone. That's why, within the limited framework of our concerts, we have also outlined his environment and, for example, the Missa "Et ecce terrae motus" from Antoine Brumela contemporary of Josquin. With its twelve voices - the norm at the time was four - it is one of the most spectacular works of the Renaissance, and is sometimes reminiscent of American minimal music. Steve Reich, for example.

A bold comparison.

This is not so far-fetched when you consider that Reich explicitly refers to the third Agnus Dei from Josquin's Missa "L'homme armé sexti toni" where the four upper voices are led in pairs in canon and the tenor and bass sing the melody of the chanson L'homme armé simultaneously forwards and in a crab. Such canonic feats inspired Reich.

-

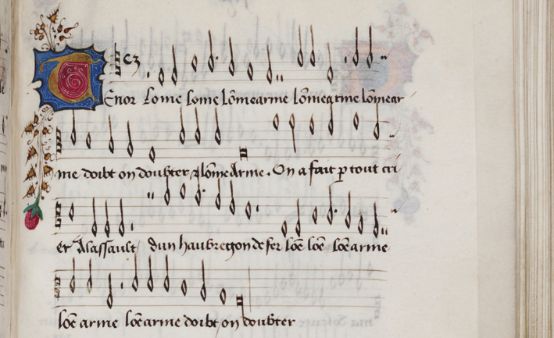

"L'homme armé" in the "Mellon Chansonnier", 1470, 45r

Max Nyffeler: Your program also includes numerous chansons by Josquin and others.

Roland Wächter: These secular polyphonic songs are an important branch of Josquin's oeuvre. French composers such as Clément Janequin and Claude Le Jeune followed on from him and took the polyphonic chanson genre to its peak.

What is the much-cited historical significance of Josquin?

On the one hand, he builds on predecessors such as Guillaume Dufay and Johannes Ockeghem, who shaped the then-novel structure of a harmonic movement with equal voices. On the other hand, he enriches this vocal movement with an expressiveness that did not exist before. With Dufay and Ockeghem, the focus is still on the constructive, such as canonic voice leading, whereas with Josquin the meaning of the words now also plays a role. In many works, one can observe a direct connection between words and music. That brings him closer to us. But the question is, of course, to what extent we still have an ear for these expressive values today.

Paths to a new sense of sound

Max Nyffeler: Josquin's music is also much more consonant than that of his predecessors, and the harmonies become more two-dimensional.

Roland Wächter: With Dufay and Ockeghem, the harmony still has something harsh and harsh. Josquin spent many years in Italy, and the Italian influence probably brought a new kind of transparency and suppleness to his music. It sometimes has something downright sweet about it, which cannot be said of Dufay or Ockeghem. For example Tu solus qui facis mirabilia or Ave Maria virgo serena: Such pieces have an immediate effect, and the Frottola El Grillo is almost a hit.

There is a parallel to the visual arts of his time, which also developed a completely new sensual aura, even with religious motifs.

Absolutely. His direct descendants also made this reference and said: Josquin, with his sensuality and expressiveness, is the Michelangelo of music, so to speak.

Was Josquin's artistic development straightforward or erratic? He led a rather erratic life.

This is difficult to answer, as only a few works can be dated. The printed editions by Ottaviano Petrucci in Venice, which appeared from 1502 onwards, do provide a clue. However, as they do not contain the dates of origin of the works, we are more or less in the dark. Musicologists therefore attempt to reconstruct the stylistic development on the basis of the available data. According to this, Josquin began in the tradition of his predecessors Dufay and Ockeghem: there is a cantus firmus in the tenor, consisting of a fragment of Gregorian chant or a chanson, and the canons of the other voices entwine around this framework. This canon technique with its variants of the original melody - cancels, inversions, cancels of inversions, shortening, stretching etc. - is an essential feature of earlier Renaissance music. Josquin obviously departs from this in his middle phase, because here the cantus not only appears in the tenor, but can also wander through the other voices, resulting in imitative procedures. The voices thus participate in a common motif. In his final creative phase, this all develops in the direction of a relatively free compositional technique, where he arranges the material according to more subjective criteria.

Composer in a warlike era

Max Nyffeler: Josquin Desprez (or des Prez) was probably born in 1450 near Saint-Quentin in what is now northern France and died in 1521. He lived in the so-called High Renaissance, a time of extremes: on the one hand a heyday of the arts and sciences, on the other a time of great upheavals and wars. In 1477, the Confederates defeated Duke Charles the Bold at Nancy, bringing down the mighty Burgundian Empire, a great economic and musical power. In 1492, Columbus discovers America, and in 1517 Luther formulates his 95 Theses, which mark the beginning of the Reformation. This raises the question: are these conflicts echoed in Josquin's music? Or is it simply "timeless"?

-

The basilica of Saint-Quentin. Photo: Pierre Poschadel/WikiCommons

Roland Wächter: Religious music is about eternal truths and not about the temporal with war, plague and famine. At best, the temporal is reflected in his secular music, especially in the chansons. They have a distinctly melancholy tone and mostly deal with emotional pain and unfulfilled love. You can already see it in the titles: Mille regretz and Adieux mes amours. Or Fortuna desperataa desperate, hopeless fate. Josquin also wrote a parody mass on the melody of this chanson, as well as on the chanson Malheur me bat by Ockeghem.

-

"Melencolia I", copperplate engraving 1514 by Albrecht Dürer

Max Nyffeler: Melancholy really does seem to have been a zeitgeist phenomenon, just think of Dürer's engraving "Melencolia I" from 1514.

And then there's the song that was popular at the time L'homme armé, which refers to war and was used by Josquin and many others as a model for cantus firmus masses. We must not forget: At that time, it was the task of princes to wage war, as strange as that sounds today. It was about securing and expanding their sphere of power.

And control of the trade routes, in other words economic power. This played a major role for Burgundy in particular. It was already a form of early bourgeois economy that developed in the dukes' Dutch possessions in the 15th century.

From Burgundy to Italy and back

Roland Wächter: It is remarkable that almost all the leading Renaissance composers, the so-called "Netherlanders", came from a core area of these Burgundian lands, namely from what is now the border region between France and Belgium, the Hainaut, or Hainaut in German. This can be explained by the wealth of this region at the time, from which the ecclesiastical singing schools, the so-called maîtrises, probably also benefited. The musicians trained here were often hired out to Italy. Ockeghem was one of the few exceptions. But Dufay commuted back and forth between his homeland and Italy, Josquin spent a long time in Italy in his early years, and composers such as Adrian Willaert remained there and even had an Italianized name like Cipriano de Rore.

Max Nyffeler: The composers presumably followed the trade routes installed across the continent by the leading trading and money houses in Burgundy, the Medici in Florence and others. It is therefore reasonable to conclude that their patrons also sent them on their travels as a cultural bonus to their business relationships.

Many of these composers - in the understanding of the time, they were actually singers, the profession of composer did not yet exist - were also high-ranking secretaries to princes and churchmen and often traveled on diplomatic missions for their patrons. On the other hand, there was a lot of money at the Italian royal courts, and this was used to satisfy the need for cultural representation.

Courted and highly paid by princes

Max Nyffeler: In his seminal work "The Culture of the Renaissance in Italy", Jacob Burckhardt points out that there was real competition among the princes in the display of splendor. The famous artists were lured to the courts with high fees and privileges.

-

Ercole d'Este (1431-1505). Dosso Dossi (1469-1542)

Roland Wächter: There is an anecdote about Prince Ercole I of Ferrara, who is looking for a new musician and sends his agents around Europe. One of them writes to him: "Since only the best is good enough, only either Heinrich Isaac or Josquin Desprez come into question. Isaac is very sociable with the musicians, he composes what you order from him and he comes for 120 ducats. Josquin, on the other hand, is a difficult type, he only composes when he wants to and charges 200 ducats." For the prince, however, it was quite clear: he had to have Josquin. Back then, music had a representational function that we can no longer imagine today. Today, the super-rich own football clubs.

Judging by the salary payments, he was only in Ferrara for a short time, from 1503 to 1504. Before that, he was a member of the papal chapel in Rome for a long time, perhaps in Milan with the Sforza family and probably in the service of the French king for two years from 1501. Many dates in Josquin's life are uncertain. He probably left Ferrara in 1504 due to the plague and traveled back to his homeland, to Condé-sur-l'Escaut in Hainaut, where he held a high ecclesiastical office until his death in 1521.

A Beethoven of the 16th century

Max Nyffeler: How was Josquin perceived after his death?

Roland Wächter: For the next two or three generations of composers, he was an undisputed authority.

It's almost reminiscent of Beethoven's impact in the 19th century.

The comparison is certainly apt. However, Beethoven had an intimidating effect on subsequent generations. With Josquin, the opposite is true: the exemplary quality attributed to his works challenged later generations to imitate them.

Petrucci's printed music played an important role in this establishment as a "classic".

Josquin is the first composer in music history to have an entire volume dedicated exclusively to him; Petrucci's print dates from 1502, Missae Josquincontains five of his masses. This shows the importance that was already attached to him during his lifetime. Josquin was undoubtedly involved in the project and used the new medium of printed music to disseminate his music. The mass volume went through three editions, which means that it was sold and found an audience. But then Josquin also appears in the writings of theorists such as Glarean, who worked in Basel and saw Josquin's loosened-up polyphony as an exemplary compositional model.

Martin Luther already said of him: "Josquin is the master of music; they have to do it the way he wants."

Josquin is also celebrated as the great composer by authors outside the world of music. His influence extends as far as Palestrina, Orlando di Lasso and Tomás Luis de Victoria, i.e. right up to the threshold of the Baroque era.

Then his reception obviously loses its power. Why is that? That was not the case with his contemporaries in the visual arts such as Leonardo, Raphael and Michelangelo.

There are probably two reasons for this. Around 1600, there was a major paradigm shift from polyphony to accompanied solo singing, monody, where the passionate expression of the subject takes center stage, and to basso continuo. Monteverdi, who still mastered both styles, is exemplary of this change. The other reason lies in the fleeting nature of music itself. A picture, once painted, remains for a long time. But a score simply disappears into a drawer if it is not brought to life again and again. Because let's not forget: In the past, only "new music" was ever performed, i.e. pieces composed for the here and now. The fact that Orlando di Lasso composed the famous (and now also programmed by us) Missa "Et ecce terrae motus" by Antoine Brumel is a major exception. In doing so, he saved the work for posterity, as his copy remains the only source to this day.

Performing and listening to Josquin

Max Nyffeler: It was the composers who later kept the memory of Josquin's music alive.

Roland Wächter: But his works, like Renaissance music in general, were no longer performed. The ever-growing audience of the new era obviously couldn't or didn't want to put up with it. It was only in the 19th century, with the rise of historicism, that this music slowly came back into focus.

Today, Josquin still seems to be a case for special ensembles and a special audience.

Absolutely. The entire Renaissance period is still a fringe area of musical life. The last major appropriation of early music concerned Monteverdi in the seventies and eighties of the 20th century. This was mainly through opera, which made it easier to appreciate. But music before 1600 is still a specialty. Performers first have to work their way into it.

As far as performance practice is concerned, much is still unclear and will probably remain so. Recently, there has often been talk of mixed vocal-instrumental scoring, but the details are obviously not so clear.

We know these works in purely vocal versions from the older leading interpreters such as the Hilliard Ensemble, the Tallis Scholars or Philippe Herreweghe. This is certainly the main possibility, but not the only one. There are probably also different local traditions, for example the Sistina in Rome was always sung a cappella. In other places, instruments were used; there are corresponding illustrations and references in the sources. But how they were used in detail is not known. Younger ensembles today work with mixed instrumentation, for example the groups thélème or The Earle His Viols by Elisabeth Rumsey, who also perform here.

The audience also has to develop an ear for this music first.

Apart from a few pieces, we usually have no direct access to it, unless we simply enjoy its melodiousness and are satisfied with it. But where you find Josquin most often today, and interpreted in excellent and different ways, is on recordings. There is a wide range on offer here.

And that obviously sells. So there is a larger audience for it after all.

It's just not enough for continuous concert series. But the CD market is working. At least half a dozen CDs with music by Josquin have been released in the last few weeks, which of course has to do with the 500th anniversary of his death this summer.

A source of inspiration for today's composers

Max Nyffeler: Fortunately, composers of the 20th and 21st centuries are also showing a growing interest in Renaissance music.

Roland Wächter: One of the first was Anton Webern, who wrote his doctoral thesis on Heinrich Isaac in 1906, which undoubtedly had an impact on his structural thinking in the later twelve-tone works. The great choral work by Ernst Krenek, Lamentatio Jeremiae Prophetae, composed in the spirit of the old vocal polyphony, should also be mentioned.

Klaus Huber has referred to Renaissance composers unusually often: 1979 in "Beati pauperes II", a - in his own words - "contrafacture" of the motets "Beati pauperes" and "Beati pacifici" by Orlando di Lasso, 1992 in "Agnus Dei cum recordatione", a "Hommage à Jehan Okeghem", based on his "Missa prolationum", in 1997 in "Lamentationes Sacrae et Profanae ad Responsoria Iesualdi" with reference to Gesualdo and in 2006 with "Miserere hominibus", premiered in Lucerne, which not only uses Arabic scales, but with its polyphonic, instrumental/vocal mixed movement also makes recognizable reference to Josquin. These are just a few of Klaus Huber's works influenced by Renaissance techniques.

Steve Reich, too, with his reference to Josquin's Missa "L'homme armé sexti toni" should be mentioned again. He regards the methods practiced here as exemplary for minimal music.

In England, it was the composers of the so-called Manchester School, above all Peter Maxwell Davies, who studied the scores of the Renaissance masters and made them fruitful for their own music. In this case, however, it was the English composers of the 16th century such as John Taverner and Thomas Tallis.

And Ralph Vaughan Williams also referred directly to Tallis. You could probably find many more such references to tradition in the music of our time. This shows that the Renaissance is by no means a historically dead epoch.

Discography

New recordings 2020/21, which also reflect the different interpretations currently possible.

1. purely vocal interpretations

The Golden Renaissance: Josquin des Prez

Missa "Pange lingua" and motets

Stile antico

Decca 485 1340

Josquin: Motets and Mass Movements (motets and individual mass movements)

Brabant Ensemble

Hyperion CDA 68 321

Josquin des Prez: Missa Hercules Dux Ferrarie, Missa D'ung aultre amer & Missa Faysant regretz

The Tallis Scholars, Peter Phillips (conductor)

Gimell CDGIM051

(On the longlist 1/2021 - German Record Critics' Award)

2. vocal-instrumental interpretations

Josquin des Prez: Adieu mes Amours

Romain Bockler (baritone solo) and Bor Zuljan (lute)

Ricercar RIC 403

Josquin Desprez: Stabat Mater

Motets and instrumental chansons

Cantica Symphonia

Glossa GCD P31909

Le Septiesme Livre de Chansons - Chansons by Josquin Desprez

Ensemble Clément Janequin

Ricercar RIC 423

3. purely instrumental interpretations of vocal works

Josquin des Prez: Inviolata

Motets and mass movements in versions for solo lute

Jacob Heringman, lute and vihuela

Inventa INV 1004

FURTHER LINK

One Youtube video of many

Here the crab form of the III Agnus Dei from Josquin's Missa "L'homme armé sexti toni" visualized by the zoom going backwards again with the image of Raphael in the 2nd half (see the analysis in the commentary to the video).