The breathing lightness of the game

The violinist Hansheinz Schneeberger had great human strength and left behind deep musical traces. On the first anniversary of his death, companions and friends came together to make music.

Bartók was one of his fateful composers. Schneeberger played the 2nd Rhapsody with Ansermet in 1946. From then on, he was regarded as the best violinist in Switzerland. Soon afterwards, he was able to give the Swiss premiere of Bartók's 2nd Violin Concerto. This in turn led to the premiere of the 1st Violin Concerto, which was only published posthumously. In 1952, Schneeberger took over the premiere of Frank Martin's Violin Concerto.

Schneeberger was a singular phenomenon as an artist, teacher and person. He always reacted directly. He was always on the lookout for better solutions. The pianist Jean-Jacques Dünki, one of his long-standing chamber music colleagues, recounts that even in old age, Schneeberger was still enthusiastic about a new fingering and immediately played it for him. The violinist worked on a breathing, light bowing technique: "He spent decades of his life tinkering with an extension of the bow stroke," says Egidius Streiff, who was a junior student with him at the Basel Music Academy. He was able to "spin" phrases on a bow almost endlessly and thus created his very own style.

Heinz Holliger, with whom he had a decades-long friendship, recalls: "His bowing was based on breathing ... He was interested in making the essence of the piece resound. To achieve this, he was prepared to question everything he had ever learned. He was the greatest role model a musician can be: never satisfied with himself and always discovering something new."

As a tall and heavy man, he worked on the ease of playing. He trained this lightness through his great hobby, ice skating, which taught him a completely new philosophy of violin playing: "You must not disturb the flow of movement. The one must emerge harmoniously from the other. If you mess up the movement at the beginning, the whole figure is broken," he said in an interview broadcast by SRF on the occasion of his death.

As a teacher, he was a primal force and left no doubt as to how he wanted things to be: "I'll do it this way," his students often heard when they were looking for musical solutions. After a concert, he could show his complete enthusiasm, but also his total dislike. Egidius Streiff reports: "I found him to be a very open-minded person. He was extremely broadly interested and wanted to know about everything that interested the pupil".

Favorite composers, favorite people

In the Great Hall of the Basel Music Academy, where Schneeberger had taught for 30 years, composers who had been among his favorites were performed on October 21, as well as pieces with an inner connection between the honoree and the performers.

Heinz Holliger began with an exemplary demonstration of what breathing music-making can mean in the Adagio from Mozart's oboe quartet. Intarsimile for solo violin from 2010 was originally composed by Klaus Huber for Schneeberger, but in the end his student Egidius Streiff took over the premiere; he was also on the podium this time. Heinz Holliger's enthusiasm for Schumann began when he heard Schneeberger play Schumann as a young student: "He had the key to this music," Holliger is convinced. Listening to Daniel Sepec and Tobias Schabenberger play Schumann's Sonata No. 1 in A minor was pure pleasure. Streiff had shown his teacher the Reger Sonata in E minor. Schneeberger was so enthusiastic about it that he promptly recorded it together with Jean-Jacques Dünki. Dünki and Streiff performed the work that evening.

-

Heinz Holliger, Robert Koller, Mariana Doughty and Tobias Moster. Photo: Niklaus Rüegg

French music "mues schmöcke"

French music was particularly close to Schneeberger's heart: "French music must taste good", he used to say. This olfactory character could be felt in the Allegro from Fauré's piano quartet with Gérard Wyss, Helena Winkelman, Mariana Doughty and Tobias Moster. The young Dmitry Smirnov, accompanied by Jean-Jacques Dünki, artfully spun the musical threads in Debussy's Sonata for Violin and Piano in G minor. He was able to benefit from Schneeberger's advice in the last months of his life. His last gift to his friend Heinz Holliger was the complete edition of the Ravel letters. In the Allegro of the Ravel Sonata for violin and cello, Ilya Gringolts and Anita Leuzinger skillfully played the awkward intervals to each other. Heinz Holliger had prepared the solo sonata Ri-Tratto (2011) and was inspired by the fugue from Bartók's solo violin sonata, which Schneeberger had often played. Ilya Gringolts performed it with a determined touch. He then offered a breathtaking version of the fugue.

-

Bourrée - a composition by nine-year-old Hansheinz

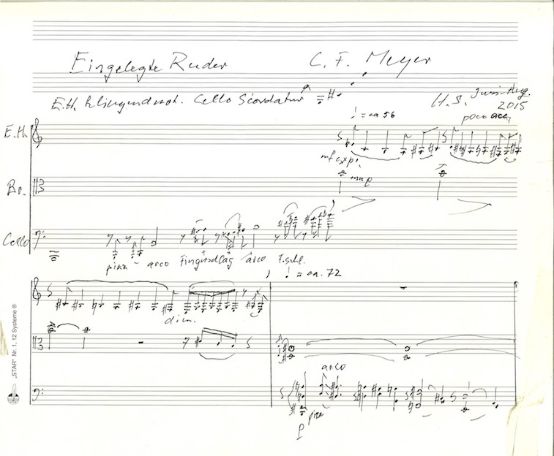

The fact that Schneeberger had also composed, albeit largely in secret, became clear in the next part of the program. He had already started at the age of nine. Even then, his pieces were perfectly composed and displayed an original, personal language. Isabelle Schnöller joined those already mentioned for his two Haikus for flute and string trio (2011). In the first piece, flagolettes and bird calls could be heard; in the sound clusters of the second, one believed to recognize images of nature. Eingelegte Ruder (2015, picture at the bottom) for baritone, cor anglais, viola and violoncello is reminiscent of Franz Liszt's late work La lugubre gondola. Robert Koller has created C. F. Meyer's meaningful text over a sombre mood.

The program concluded with a light-hearted violinstafette with practice duets by Béla Bartók, which Schneeberger knew inside and out, as they were on the desk of his violin teacher Walter Kägi. He had been in constant contact with Bartók, who sent him the pieces to try out.

-

Violin relay from left: Helena Winkelman, Dominik Stark, Daniel Sepec (front), Egidius Streiff (back), Ilya Gringolts (front) and Dmitry Smirnov. Photo: Niklaus Rüegg

-

Schneeberger's composition from 2015. scans: zVg