"A heavenly work" - very human

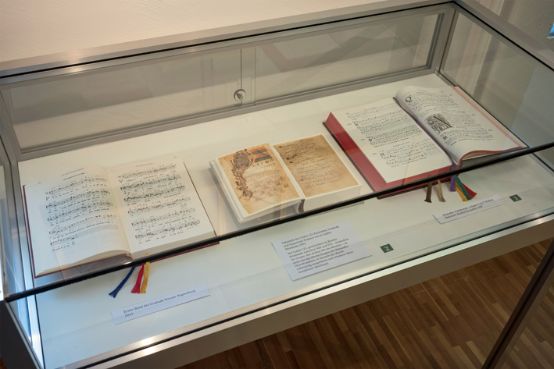

The Fram Museum in Einsiedeln is currently exhibiting the musical treasures of the Einsiedeln monastery's music library. They date back over a thousand years and portray the musical life of the Benedictine monastery in unexpected ways. The author of our report was a student at Einsiedeln Abbey from 1963 to 71 and experienced some of this history at first hand ...

Father Roman Bannwart, sitting to my left, pushes the slider down; the lights go out in the hall. The "hall" is the gymnasium of Einsiedeln Abbey School, the time: Fasnacht 1966. The orchestra plays a piece of music that I have since learned to call an "overture". It is the first overture in my life - and also the last, so to speak. And it opens Franz Schubert's Singspiel "Die Zwillingsbrüder". I sit to the right of Father Roman in the prompter's box and have to give the singers their cues in the speaking parts.

Opera tradition

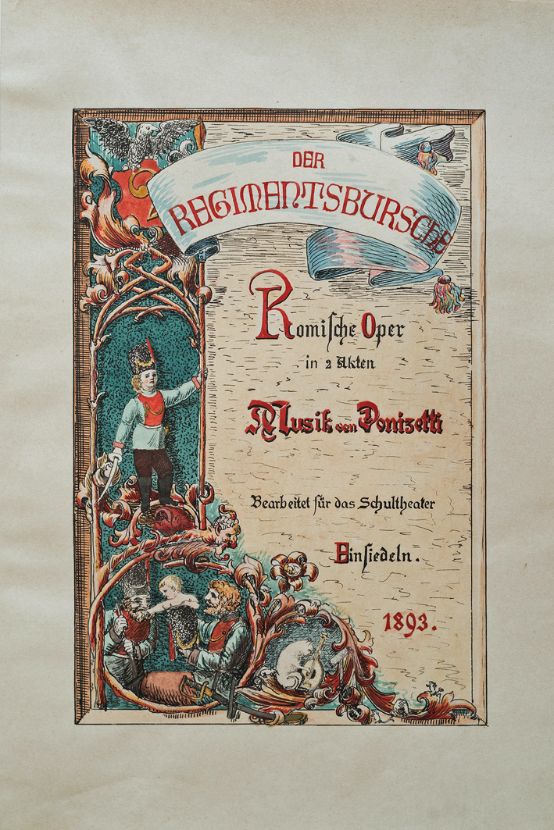

What Father Roman doesn't know, and I know even less, is that the 1966 Fasnacht opera - alongside the Twin brothers Schubert's one-act play The four-year post a long tradition comes to an end. It is the tradition of opera performances in the monastery, which has been documented in the monastery since 1808. The opera-loving monks and, under their guidance, the pupils of the grammar school dared to try their hand at many things: Mozart's Abduction from the Seraglio (1833), to Donizetti's Daughter of the regiment (1860) or to Auber's The mute of Portici (1890). However: From the love drama of the Kidnapping was a father-son story (The Turkish cadets), the regimental daughter became a regimental boy, the mute became a mute - the monks and pupils were probably not supposed to be shown too much of the opposite sex on stage. In later years, this drastic "re-writing" was omitted; the two operas that I experienced were performed more or less in the original, of course with boys in the (female) soprano and alto roles. Father Roman - known throughout Switzerland as a chorale master at the time - did not always just act as chief lighting technician either: a photo in the exhibition shows him in the leading role in an opera by Albert Lortzing in 1937.

-

The regiment's daughter became a regimental boy. Photo: Museum Fram

In 1965, the year before Schubert and therefore as the second last opera, a piece by a then virtually unknown composer was staged. It was called Orfeo and was by a certain Claudio Monteverdi - strange music! Some 20 years later, I was to experience Nikolaus Harnoncourt's performance at the Zurich Opera House - and some of the opera's melodies seemed strangely familiar to me. The role of Plutone in the Einsiedeln performance was sung by a student called Arthur Helg - as Father Lukas Helg, he is now one of the two curators of the exhibition.

Sacred music

And opera not only had its place on the stage, but also in monastic services: arrangements of passages from Mozart's operas were often performed there - the same music with a new, sacred text. The in-house composers were very skillful in this kind of appropriation and - to put it soberly - also quite unquestioning. Gregorian chant, on the other hand, which today is the "trademark" of monastic worship, was hardly sung at that time.

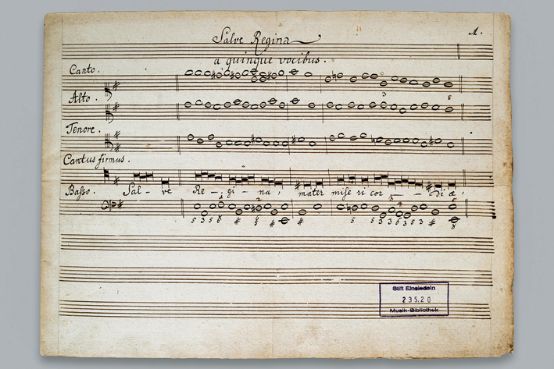

The emblematic piece of music of the monastery, the polyphonic Hermit Salve Reginawhich the monks sing daily in the Chapel of Grace. The piece exists in various arrangements of the Gregorian (monophonic) original; and the version for male voices only, which is regularly sung in front of the Chapel of Grace today, is musically not unproblematic, as it is actually intended for an upper voice for choirboys.

-

"Einsiedler Salve Regina". Photo: Museum Fram

In addition to Father Roman, our second music teacher and the monastery's bandmaster was Father Daniel Meier; incidentally, he played the Knusperhexe in Engelbert Humperdinck's Hansel and Gretel. He now forgot to celebrate with our year of choirboys the Salute and, after a while, indignantly reprimanded our still uncertain singing along. So although I enjoyed singing the "Salve" - its full-toned, organ-like sound had something overwhelming about it inside the Chapel of Mercy - I was still a little timid for a long time ...

Monastery composers

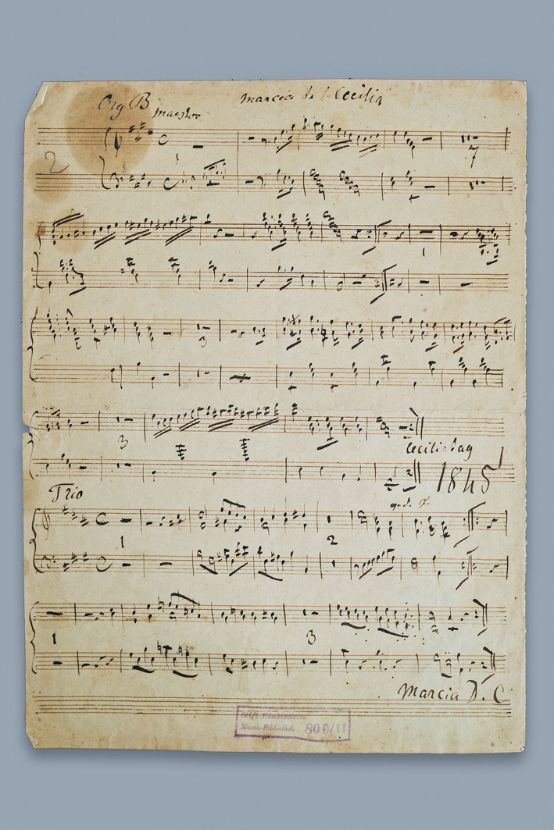

Father Daniel Meier (1921-2004) was a composition student of Paul Hindemith in Zurich for several years; greeting postcards with Hindemith's own drawings even testify to a kind of friendship. Father Daniel is one of an impressive number of monastery composers (over 30 in total), some of whom have composed several hundred works; the youngest to date is the equally prolific Father Theo Flury (*1955). This shows a special development in the history of music: up until the 19th century, important composers also composed sacred music, which could be performed by talented amateurs and was therefore readily taken up by the monastery musicians. However, this changed with the radical new music of the 20th century: sacred music that could be used in Sunday services became the preserve of composers who did not want to represent a modern or avant-garde style, and the Einsiedeln composer-monks were among them. Their fate, however, is that their "utility music" is hardly ever played in the concert hall. But they did not always compose only pious music: the monastery hit is still a groovy Caecilia March for three organs, written by Father Anselm Schubiger in 1845.

-

"Caecilienmarsch" for three organs by Father Anselm Schubiger. Photo: Museum Fram

Hits of a completely different kind were contained in a print from 1520, which can also be found in the exhibition: The Liber selectarum cantionum - a magnificent volume compiled by the "Swiss" composer Ludwig Senfl - contains 25 works by the most famous composers of the High Renaissance. Josquin Desprez and (somewhat immodestly) Ludwig Senfl himself are represented with most of the works. The strange thing, however, is that the volume shows practically no signs of use; the monks seem to have bought it as an "art object" rather than for everyday use. This may correspond to the fact that the two Renaissance works that we regularly sang in church services were not by composers such as Josquin or Senfl. Rather, they were the Missa Papae Marcelli by G. P. da Palestrina and the Requiem by his pupil G. F. Anerio, which continued the Renaissance style in a somewhat tensionless, elegant melodiousness.

Music library

It was precisely this Palestrina style that was declared a model for church music in the 19th century - with not always entirely happy consequences. After all, whereas in the past everything "outdated" had been ruthlessly discarded as unfit for reuse, the music of earlier epochs was now once again taken note of and collected. This historical interest also arose in Einsiedeln Abbey; a real music library was created, the beginnings of which can be traced back to the collecting activities of Father Gall Morel (1803-1872). To name two contrasting examples, the monastery owes him a treasure such as Mozart's handwritten sketch for his Paris Symphony and the curiosity of the pseudo-Renaissance madrigals of the Englishman Robert Lucas Pearsall, who was living at Wartensee Castle (St. Gallen) at the time; he not only donated his own works to the monastery, but also the extensive music library. Donations of this kind helped to make the monastery's music library one of the largest in Europe today.

-

Mozart's handwritten sketch of the Andante con Moto from his "Paris Symphony". Photo: Museum Fram

In the late 19th century, interest in early music also turned to Gregorian chant. The monastery owns the Codex 121 the oldest surviving gradual with monophonic Gregorian chants for the entire church year. The manuscript, written in Einsiedeln before the year 1000, can (naturally) only be seen as a facsimile in the exhibition - but even this, with its mysterious notation of the neumes, is capable of awakening a quiet shiver. At least today. Because it would be a lie to claim that I particularly loved Gregorian chant back then as a monastery pupil; no, it always seemed a bit boring and monotonous to me, even if Father Roman had patiently taught it to us ... So the past can still catch up with us even after more than 50 years.

Exhibition

The exhibition offers a musical history of its own kind: much that is otherwise important does not appear here; and what was important in the monastery was and is only occasionally taken note of outside. But this is precisely what makes the exhibition so appealing, together with the wealth of manuscripts, prints, biographies, contemporary documents and sound samples - presented in a visually inviting way and clearly structured into manageable "chapters". This structure is also followed by accompanying documentation; and Father Lukas Helg's guided tours, which are anything but academic, contribute to the exhibition's appeal. But of course this and that also remains open: Why did that tiny miniature from 1659 with Calvinist (!) psalms come to the monastery ...?

The exhibition runs from May 25 to September 29, 2019 Museum Fram, Eisenbahnstrasse 19, Einsiedeln

www.fram-einsiedeln.ch informs about opening hours and guided tours

P. Lukas Helg / Christoph Riedo: A heavenly work - Musical treasures from Einsiedeln Abbey. Documents on the exhibition at Museum Fram. 110 pages, with numerous illustrations

P. Lukas Helg: The Einsiedeln Salve Regina - A musical study. 126 pages, with music examples