In the labyrinth of evil

Giorgio Battistelli's music theater piece "I Cenci" had its Swiss premiere on 26 May at the LAC Lugano as a co-production of LuganoInScena and the 900presente concert series of the Conservatorio della Svizzera Italiana.

A breathing noise, a few flickering sounds, a suppressed scream, an expressionist ostinato figure: Giorgio Battistelli is a master at creating an unmistakable atmosphere with just a few sounds, and in his music theater piece I Cenci announces in the very first bars something of the oppressive feeling that will spread through the auditorium over the next five quarters of an hour. The plot of the four-person play, which premiered in English at the Almeida Theatre in London in 1997 and has now had its Swiss premiere in Lugano, is as succinct as it is brutal. It is set in Renaissance Rome and centers on the corrupt and morally depraved Count Cenci. He rapes his daughter Beatrice, who murders him with the support of her mother and fiancé and is ultimately executed. The evil story is based on real events from 1599, when there was a laughing third party, the Pope. He took advantage of the family's ruin to get his hands on Cenci's fortune, with whom he had business connections.

The material inspired Shelley to write a play in 1820 and Stendhal to write a novella in 1837 in his Chroniques italiennes. Antonin Artaud based his four-act play on these two sources in 1935 Les Cenciand this in turn served Battistelli as a model for his libretto. Artaud exaggerated the story to monstrous proportions, and the fragmentary, short sentences that Battistelli distilled from the original text sometimes seem like stabs to the living flesh. Artaud's idea of a "théâtre de la cruauté", which is intended to bring out the affects in their raw state and freed from all conventions, remains omnipresent in Battistelli's artificial reading. Count Cenci, portrayed by Roberto Latini as a coolly calculating monster, is a libidinous egomaniac who imagines the rape of Beatrice (Elena Rivoltini) as the destruction of her ego. When he monologues about his feelings, he takes over the narrative perspective and we descend with him into the deepest abysses of his psyche. It is at such moments that Artaud's terrifyingly precise view of the evil in man comes to the fore.

Meaningful surround sound

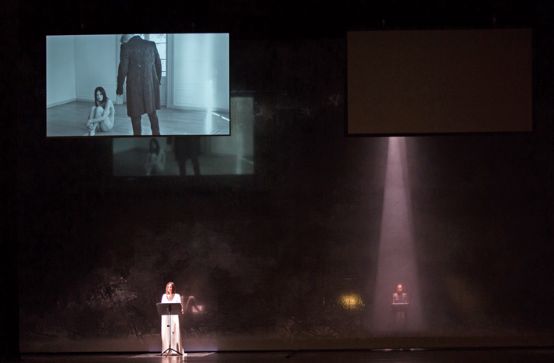

Battistelli has artfully split the stage narrative into text, music and scene. By dispensing with singing - the four performers have pure speaking roles - he has created a melodrama that is given a spatial dimension through the use of microphones and live electronics. While the speaking roles distance the action, as in epic theater, the emotional potential of the drama unfolds primarily in the music. It comments on and deepens the spoken word in an effective way, but without any overheating. Battistelli has also included image projections as a further element.

Carmelo Rifici's production benefited from the conceptual openness of the original and tended towards multimedia theater. In Francesco Puppini's video projections, which ran simultaneously on several screens, the actions mentioned in the text and only hinted at in the play were shown as film sequences in black and white. We followed the camera through long corridors, staircases and corridors of rooms in a deserted palace - a clinically clean, nightmarish scene in which the master of the house wandered around like Minotaur in his labyrinth, stalking his daughter and finally hunting her down like a frightened deer. To brighten up the dark perspective at the end, a solo dancer (Marta Ciappina) was allowed to dance her poetic circles as an epilogue in Lugano - Beatrice was not supposed to die.

The spatial sound carefully modeled by Fabrizio Rosso (sound direction) and Alberto Barberi and Nadir Vassena (live electronics) made a decisive contribution to the dramatic intensification and spatial expansion of the action. It arched over the entire auditorium, with a total of over two hundred settings pre-programmed. The voices and instruments were discreetly amplified, transformed in places and moved around the room. Cenci's ominous footsteps in the empty palace circled above the rows of spectators. Francesco Bossaglia at the conductor's desk kept the complex musical progressions firmly under control at all times.

Enrichment of cultural life in Ticino

The very well-attended performance in the large hall of the new LAC was a co-production of the LuganoInScena theater association, which had engaged the professional actors, and the Concert series 900presente. The Conservatorio della Svizzera Italiana which is celebrating its twentieth anniversary this year, provided the sixteen instrumentalists, all advanced students, as well as the extensive technical team involved in the sound and visual realization.

With Battistellis I Cenci The project was a challenging one, especially when it came to the delicate room acoustics. The fact that it was so successful and that a performance of impressive cohesion was ultimately achieved is due not least to the harmonious cooperation and great commitment of all those involved.

Such public performances of contemporary works have been a significant enrichment of musical life in Ticino for several years. The Conservatorio della Svizzera Italiana is continuing the series this year with a performance of Shostakovich's Seventh in a co-production with the Zurich University of the Arts. This will be followed next April by a staged performance of Luciano Berio's Coro for forty voices and instruments, followed by a tour of western Switzerland.

-

- © LAC Lugano