"The eye composes"

On January 27 and 28, 2017, the symposium "The eye composes - Hermann Meier and the relationship between image and sound in music after 1945" took place at the Bern University of the Arts. The symposium was part of a research project on Hermann Meier at the Graduate School of the Arts in Bern.

The Solothurn composer Hermann Meier (1906-2002) is today one of the most important representatives of the early avant-garde of Swiss music. Always remaining in the background, Meier wrote works that were "spared" from criticism and correction and are therefore particularly original and have retained a certain individuality. His compositional techniques were also extremely independent, large-scale and often colorful.

The important task of making Hermann Meier's oeuvre known to a wider audience in the hope that his works will be given a more frequent place in the concerts of Swiss orchestras and other musicians in the future was the motive behind this symposium. Although Meier's music was rarely performed during his lifetime, he was aware of his contemporaneity. His extensive oeuvre includes over twenty orchestral works that have never been performed. His compositional style seemed too radical for the Swiss musical landscape at the time. It was not until the 1980s that some of his works saw the light of day thanks to the efforts of composer and pianist Urs Peter Schneider, who developed a close collaboration with Meier. Other important figures in the promotion of Meier's music are the pianist Dominik Blum and the composer and publisher Marc Kilchenmann, on whose initiative the Basel Sinfonietta performed two major orchestral works by Meier in 2010. (The Swiss Music Newspaper brought an Article in SMZ 1/2010, p. 18 f., Editor's note.)

Hermann Meier's estate has been held by the Paul Sacher Foundation since 2009 and has been part of the research project The eye composes will be investigated. The research is scheduled to be completed in 2017, when a monographic exhibition will also be held at the Solothurn Art Museum.

During the two-day symposium, lectures on Hermann Meier's music and graphic notation were given by Heidy Zimmermann (Paul Sacher Foundation, Basel), David Magnus (Berlin), Pascal Decroupet (Nice), Roman Brotbeck (Bern), Michel Roth (Basel), Marc Kilchenmann (Basel), Michelle Ziegler (Bern), Jörg Jewanski (Münster), Doris Lanz (Bern), Christoph Haffter (Basel) and Michael Harenberg (Bern).

The diverse program of lectures made for two varied but compact days. The focus, of course, was on Hermann Meier, his works, compositional technique and various insights into forms of graphic notation.

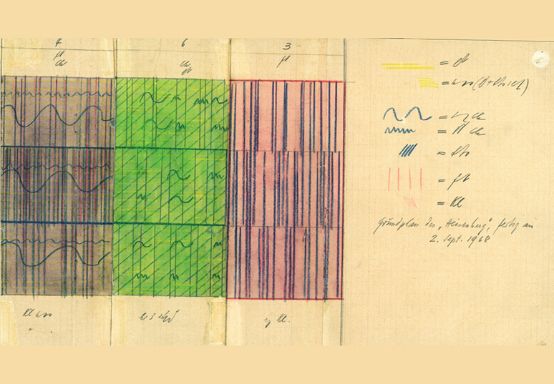

In her lecture, Heidy Zimmermann reflected on the basics of Meier's graphic works. In most cases of graphic notation, we are dealing with finished, completed scores that contain graphics or whose notation is graphic. In Hermann Meier's case, however, the graphics are used in the thought process itself, not in the finished product - the score. It was interesting to gain an insight into Meier's creative process and to be able to see some of his graphic works that are in the Paul Sacher Foundation.

Using examples of scores from the post-war avant-garde, David Magnus explained various graphic notations that are different for each composer and often cannot be assigned to any genre. The focus was on the Greek composer Anestis Logothetis and his notation, whose end product - the score - is, in contrast to Hermann Meier, a graphic system that can produce a different sound image each time it is reread.

Pascal Decroupet's lecture on the role of pictorial and graphic sketches in serial and post-serial composers was particularly interesting. After 1945, there were significant reorganizations in the areas of sound and context. New ideas led to new forms of representation, space now became an independent parameter, electronic music, aleatoric music and extended playing techniques required new visual solutions. In addition to examples from the music of Pierre Boulez, the lecture focused on Stockhausen's masterpiece Groups.

Roman Brotbeck investigated the relationship between Wladimir Vogel and his pupil Hermann Meier. Vogel had intensive contact with Meier, which later faded; after five years, the lessons failed. Meier's piano piece from 1947 and works by other Vogel students were compared. It turned out that Meier maintained his own style. Even under the influence of Wladimir Vogel, Meier sees dodecaphony not as a final goal, but as a transitory stage; he composes not only with the row, but "over the row" - like an overcoming of abstract constructivism, sometimes structured, sometimes playful in context.

Michel Roth provided a reading protocol of all of Hermann Meier's orchestral works, which seemed like a clear statement about Meier's enormous opus.

In his presentation, Marc Kilchenmann dealt with the role of graphic plans in Hermann Meier's compositional process. Meier's estate contains around 150 graphic plans and 300 sketches in workbooks. Over time, Meier's plans became increasingly complex and multi-layered. The lecture explained the relevance of the development of Meier's graphics with regard to his compositional work.

Michelle Ziegler, whose dissertation on Hermann Meier's piano works is part of the research project The eye composes dealt with Meier's electronic creative phase on the basis of the composition Sound surface structure or wall music for Hans Oesch (1970-71) and the second piece for two pianos, two harpsichords and two electric organs (1973). Meier's oeuvre is divided into different phases: the 195s were supplemented by orchestral works, the 1960s by music for keyboard instruments. Meier's phase for electronic music is clearly attributable to the 1970s, although he had already shown an interest in it earlier. Only one of his electronic compositions has ever been realized in the studio.

Jörg Jenawski spoke about the relationship between music and painting in the 20th century. He opened up the question of whether Hermann Meier had a similar relationship in his work: Meier's interest in the visual arts (especially his preference for Mondrian's works), architecture, visits to formative exhibitions, Meier's lessons with Wladimir Vogel with references to the visual arts (also the subject of Doris Lanz's lecture) - all of this indicates that the sound movements in his scores can be understood as groups of instruments, like painterly movements and areas of color.

The lectures by Christoph Haffter and Michael Harenberg dealt with specific works by Hermann Meier, the orchestral works of the 1960s, the avant-garde aspirations that this period brought with it (Haffter) and the only electronic work that was realized in the experimental studio of the Heinrich Strobel Foundation of the SWR in Freiburg (Harenberg). Using the orchestral piece from 1986 as an example, Haffter showed how Meier dealt with compositional problems and how his solutions differed from composers of his time. Michael Harenberg spoke about the conditions with which Hermann Meier was confronted in the realization of his electronic piece.

A conversation with contemporary witnesses Urs Peter Schneider and Dominik Blum, moderated by Florian Hauser, was also recorded by SRF2 Kultur and gave the audience a deeper insight into Meier's personality, his collaboration with Schneider and Blum, but also his high degree of self-criticism.

The concert by pianist Gilles Grimaître with works by Hermann Meier (including a world premiere - the piano piece from 1947) and Galina Ustvolskaya was remarkable. The concert program was an exciting mixture of different extremes: from exemplary, almost modest twelve-tone technique in Meier's Piano Piece from 1947 and charged tension in Ustvolskaya's Sonata No. 1, to the seething and ticking of the Piano Piece from 1987 and the merciless, quivering cluster chords in Ustvolskaya's Sixth Sonata, which made the hall floor tremble.

The symposium The eye composes was very successful and has come one step closer to the goal of making Hermann Meier's work better known to the public. Interestingly organized, with topics that both presented Hermann Meier as an exceptional composer and gave a good insight into the general music scene at the time and the trends during Meier's lifetime and creative period, after two days of the symposium I had the feeling that I now knew a little about the composer Hermann Meier and am eager to hear more of his remarkable music. The hope now is that there will be enough open ears in more important circles to place the name Hermann Meier in the orchestral repertoire and give him, like so many forgotten, undiscovered composers, a voice and thus say something meaningful, thoughtful or important about their (and our) time. By (re)discovering valuable legacies that our culture has left us, we have the chance to make the canon we pass on less one-sided and superficial.

The symposium contributions will be published on the occasion of a Meier exhibition at the Kunstmuseum Solothurn in the fall.