The harmonious coarse blacksmith

The Solothurn Art Museum honors the iron sculptor, draughtsman and musician Oscar Wiggli with a tribute.

He was regarded as one of the great Swiss iron sculptors of his generation, alongside Jean Tinguely and Bernhard Luginbühl, and he welded light, physical shapes out of heavy metal: Oscar Wiggli, who died on January 26, 2016 at the age of 89. Both - the lightness and the physicality - immediately catch the eye in the small exhibition that is now on show at the Solothurn Art Museum and with which his native town is honoring him. As he once confided to the art historian Matthias Frehner, all his sculptures are ultimately female bodies. This is also clear from his drawings and ink paintings, and can be seen in the photographic "Superpositions", which were shown at the same venue in 2006 and can be viewed in the old catalog. "donner à un rêve un corps - c'est ça qui me fait vivre - et avec tout ça je suis - on est - on bascule entre rêve et rêve - on bascule entre réalité et réalité", he once noted.

"Giving a dream a body": this view is transferred to the large sculptures. In Solothurn, for example, it is now palpable in an angelic, winged figure: it is quite obviously modeled on the ancient Nike of Samothrace, which throws itself towards you on the grand staircase of the Louvre. The body seems to be flying. This work, a transformation of another work of art, is of course hardly exemplary of Wiggli, who created less from his encounter with other art and history than from his contact with the material, the matter.

From this contact arose another, the most surprising of his activities: music. The small homage in Solothurn, which is limited to two halls, dedicates a significant part to this aspect. He was interested in music from an early age: He bought two harmoniums and improvised on them, not from sheet music, but from photographs. His own compositions have been documented since the early 1980s, when he attended a synthesizer course at the Centre américain in Paris. You can almost hear the metal in them that Wiggli was working on. Together with his wife Janine, who familiarized herself with the technical equipment, he constructed his own synthesizer and over the years created an oeuvre that is unique in this country - electro-acoustic music or rather a "musique concrète", with electronically generated but also recorded sounds. Pierre Schaeffer, Pierre Henry and Edgard Varèse were his inspiration.

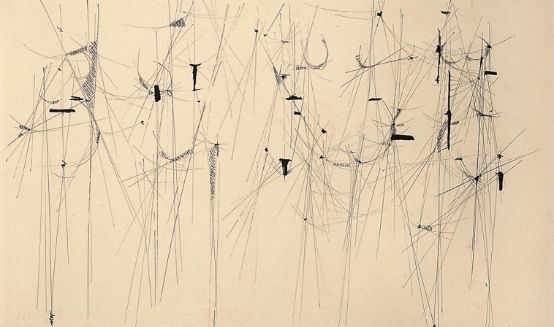

He was inspired by the theories of the Frenchman Michel Chion, but Wiggli, this self-made man, created his own foundations and put together a vocabulary of sounds with which he worked, often in French (the couple lived alternately in Les Muriaux in the Jura and in Paris): "frotté/lissé/ondulant", "éclatant/spiralant" or "frappé/implosif/lourd/agité", for example, he noted as sound associations on a drawing. With the help of words, he tried to capture what he then transformed into "évocations sonores poétiques". He created his own musical tool, his "tool", as Helmut Lachenmann would probably say.

Wiggli's scores are not conventional notations, but graphics, sound sketches. And next to them, certain ink drawings seem almost like the neumes to an imaginary music. Here, too, the sound material could be so heavy, but Wiggli's music retains a transparency, a light physicality. And it has a liberating effect at a time when the position of new music sometimes seems so gnarled and futureless. It tells a story in an immediate way: a kind of "cinéma pour l'oreille".

Further information

Hommage à Oscar Wiggli: Kunstmuseum Solothurn, until March 12, 2017. The catalog of the 2006 exhibition is still available there.

www.kunstmuseum-so.ch

https://fondationwiggli.ch

www.iroise.ch

See also the essay by Kjell Keller: A journey without end, in: dissonance, 103, September 2008.