Alpine spa and hotel music

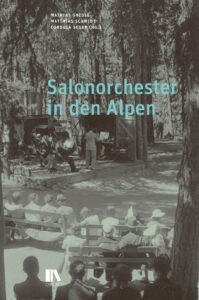

The anthology "Salon Orchestras in the Alps" presents the multifaceted history of musical entertainment in the tourist strongholds of the 19th and early 20th centuries.

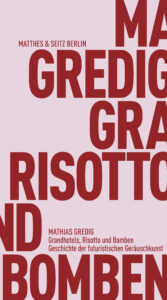

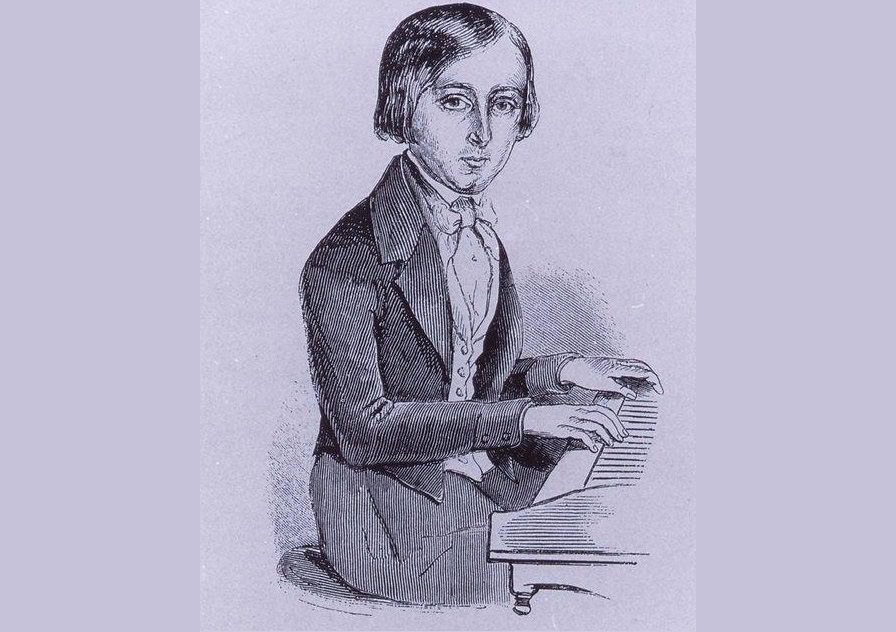

Those were the days. Rarely has this sentence been more fitting than for the world that comes to life when reading the anthology on the history of salon orchestras in the Alps edited by Mathias Gredig, Matthias Schmidt and Cordula Seger. In the course of the early tourism and health resort boom from the 1860s onwards, musical formations - from piano trios to large chamber orchestras - were hired in countless hotels to entertain international guests during their expensive stays in the Alps. This adventurous and entertaining chapter in local music history has only been discovered by music researchers in recent years.

This volume examines the topic from a variety of perspectives in 14 short essays: The arch is formed by examinations of archive documents from the Engadine hotels Val Sinestra and Maloja Palace; interspersed are texts on the history of migration (for example on female traveling musicians), music theory treatises on opera arrangements, tourism criticism, short biographies, project reports on newly written salon orchestra arrangements as well as expert discussions with a high entertainment value. In most cases, two essays are atmospherically arranged in small blocks so that there is hardly any slack in the reading.

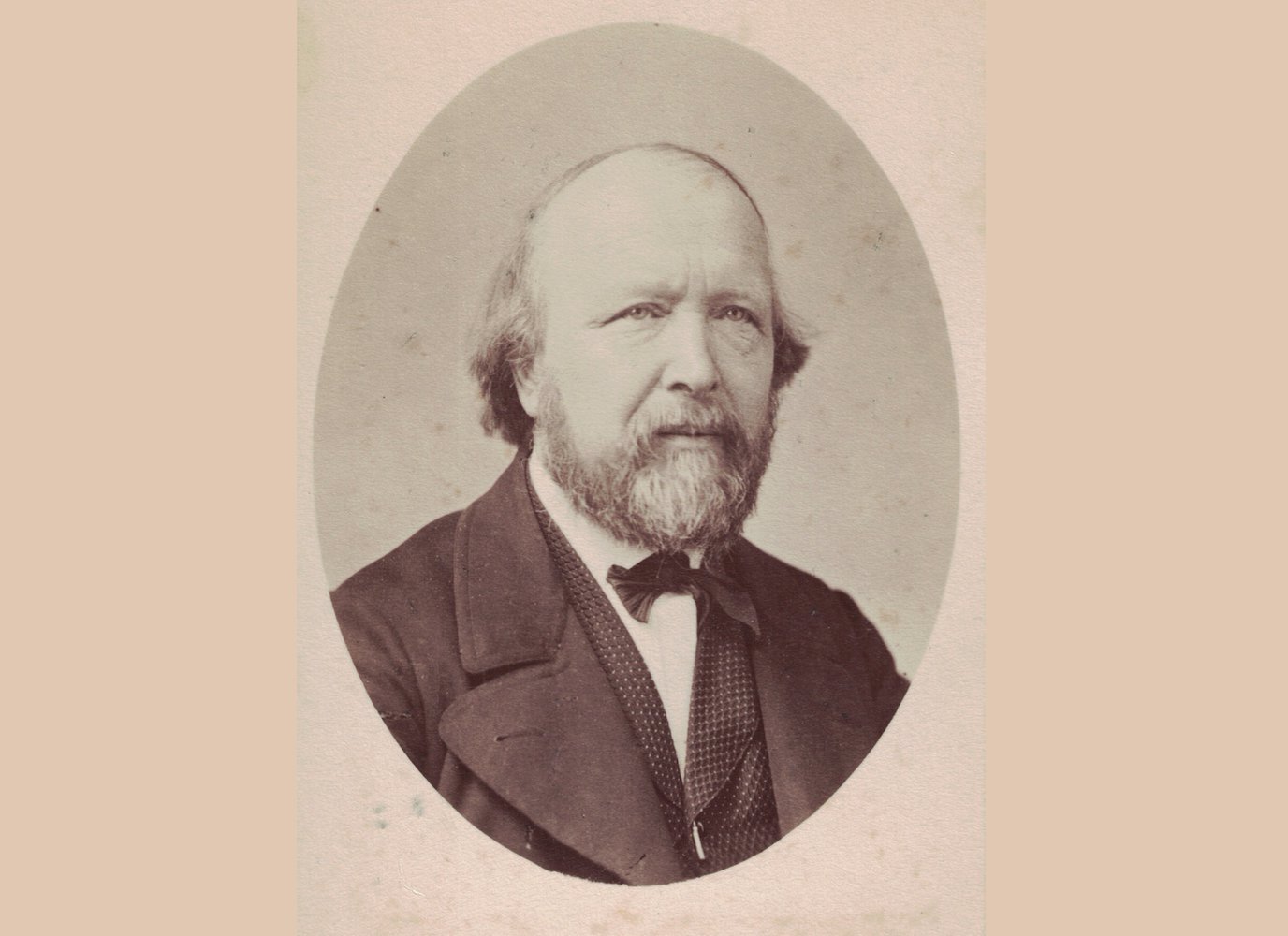

The chapters are vividly written, the variety of sources and illustrations as well as the pronounced narrativity make the texts catchy and true to life. The overall anthological structure is enriched by leading figures such as Fräulein Schubert or Cesare Galli, who appear throughout the chapters and thus gradually assemble the content into an - albeit very fragmentary - overall impression. Geographically, the excursion to South Tyrol is somewhat out of line, as the remaining contributions are almost exclusively set in the Engadine. The many concrete examples of music are a plus, from which a nice book playlist can be compiled.

The volume is definitely worth reading. It successfully combines information and entertainment and thus does justice to the subject matter.

Salonorchester in den Alpen, ed. by Mathias Gredig, Matthias Schmidt, Cordula Seger, 232 p., Fr. 38.00, Chronos, Zurich 2024, ISBN 978-3-0340-1733-6