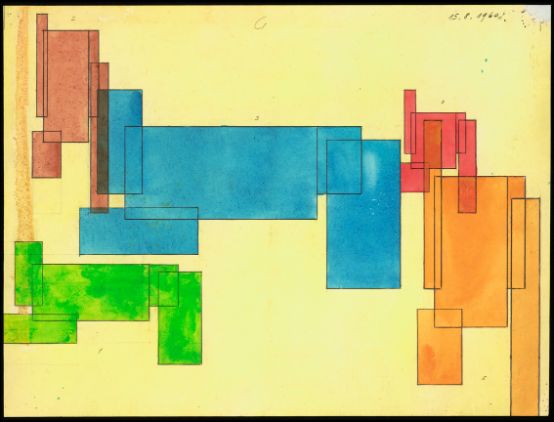

Music like a painting by Mondrian

The Kunstmuseum Solothurn is showing Hermann Meier's graphic scores until February 4, 2018. Some of the works can be heard on December 2.

"I must confess that I'm in a bad mood because of this concert. I'm trembling before it. I have anxiety dreams. Liver problems. Can't even drink wine. Terrible. This concert will surely be my last." So wrote the Solothurn composer Hermann Meier (1906-2002) on January 31, 1984 to the pianist Urs Peter Schneider, who was one of the first to repeatedly champion his oeuvre.

How would Meier have fared if he had known that people would be crowding into the entrance hall of an art museum to view his scores, sketches, drawings and plans at the vernissage? And that the Biel Solothurn Symphony Orchestra under Kaspar Zehnder would perform his Orchestral Piece No. 6 from 1957 in a subsequent concert in Solothurn's Franciscan Church, inserted between the movements of Beethoven's Fourth? How would he have felt, describing himself - in a greeting to his teacher Wladimir Vogel that was probably never sent - as "little Hans"?

Hermann Meier may serve as proof to all those who have always known that true art is created far away from the centers and their hustle and bustle. Switzerland has a few of this species, just think of Alfred Wälchli from Zofingen or the artists of Art brut. Meier is still virtually unknown, this "Schönberg from the Schwarzbubenland", although Schönberg is a bit of a misnomer. He certainly discovered atonality for himself early on, and he certainly familiarized himself with the twelve-tone technique with Vogel, but he obviously didn't like to use it so strictly, and when you hear his compositions, you understand why. This music is more geared towards tonal masses that juxtapose themselves harshly, with many pauses, very unique and uncompromising. He is more of a Helvetic Ustwolski, an erratic block, whose main profession is primary school teacher in Zullwil.

An outsider with a feel for fundamental trends

A black boy, at least in music, often gruff and edgy, with many abysses - and probably not suited to compromise. He worked on his pieces for a long time, as his sketches and plans suggest. They form the centerpiece of the Solothurn exhibition Mondrian musicwhich contains comparatively little music, but emphasizes this exhibitable aspect. And rightly so. For these "graphic worlds of the composer Hermann Meier", as the subtitle reads, point in quite different directions beyond music. Similar to Robert Strübin (1897-1965) from Basel, another outsider figure, they are eye-music or ear-graphics - and somehow typically Swiss in their unconventionality and constructive rigor: visual serialism, related to the Zurich Concretists, Max Bill and Richard Paul Lohse. Bill first spoke of "Concrete Art" in 1936, and Meier became aware of it at the end of the 1940s. Piet Mondrian's paintings were also a profound inspiration. And so he created graphic scores in the provinces at a time when the famous scores by Earle Brown, Morton Feldman and Iannis Xenakis, for example, were also being created, which have long since found their place in music history. The Paul Sacher Foundation, where the Meier estate is located, has contributed some of these scores for comparison. One find: Brown used a score for his epochal December 1952 just like Meier Millimeterpapier.

Above all, these graphics - "floor plans", as Meier called them - served him as templates for electronic music, which he worked on intensively from 1973 to 1983. Like Benno Ammann or Oscar Wiggli, he was also a lone pioneer in Switzerland in this field. In fact, you could now study all of this down to the millimetre, at least in the graphics, because unfortunately, apart from the sound layers, all projects remained unrealized: It is music in imaginary space. It is only today that the recordings are gradually being brought to sound. On "concert day" (December 2), some versions can be heard.

But it is precisely this imagination that the exhibition promotes. The overall visual impression alone is representative and extremely worthwhile. The comprehensive catalog is based on lectures given at the Meier symposium The Eye Composes last January at the Bern University of the Arts (see report by Azra Ramić at musikzeitung.ch/en/reports/conferences). Together with musicologists Roman Brotbeck (HKB) and Heidy Zimmermann (Sacher Foundation), curator Michelle Ziegler has created a Meier compendium that will hopefully help to make this music better known.

Ziegler is currently working on a dissertation on Meier's piano works; other projects are in progress. A new recording of his piano music with Dominik Blum is due to be released soon, and perhaps Hermann Meier will occasionally appear in a major concert. I wonder what he would say?

Catalog

Heidy Zimmermann, Michelle Ziegler, Roman Brotbeck: Mondrian Music. The graphic worlds of the composer Hermann Meier; 223 p. with numerous illustrations; Zurich, Chronos Verlag, 2017.