The inner workings of our brass instruments

Corrosion inside brass instruments is a largely unexplored area. A project of the HKB and other partners has investigated the topic and presented and discussed the results at a symposium.

Brass instruments don't get very old. Their mechanics wear out and the brass corrodes. Surprisingly, hardly anything is known about the corrosion inside them. While external corrosion can easily be avoided by rubbing the instrument after use (in museums by wearing gloves), the decomposition of the metal from the inside is simply accepted. Could it not be avoided? Or could corrosion at least be reduced by appropriate care, thereby extending the life of the instruments? And could this also be applied to historical instruments if they were to be played again?

A research project at Bern University of the Arts HKB together with specialists from ETH Zurich, the Swiss National Museum and the Paul Scherrer Institute investigated these questions. On Fourth International Romantic Brass Symposium the results were presented at the end of February and discussed with international experts.

Tropical climate in the tunnel system

The inner workings of a played brass instrument - a narrow tunnel system up to over ten meters long (tuba) - are hardly known. A wide variety of corrosion phenomena can occur in it, chemical changes in the metal that are mainly activated by moisture. And it is constantly damp inside. After a few minutes of playing, a tropical climate prevails with almost one hundred percent humidity. And even after playing, the interior remains damp for many days. This is simply because the dry ambient air can hardly penetrate the narrow tubes. (This is different with saxophones and flutes, as their tubing is short and many keys are open when not in use). The valve slides never dry at all, as they are cut off from the outside air.

It would actually be easy to change this. In its investigations, the research project was able to show that a fan can be used to remove all the moisture from the instrument in one to three hours, including that from the valve slides if the valves are depressed. This would greatly slow down the corrosion processes.

How does drying with a fan work?

A long-term study was subsequently able to prove the effectiveness of this treatment. Sixteen different instruments from trumpet to tuba were played daily for 14 months. Eight were treated after playing in the usual way for brass instruments, i.e. removing the condensation and leaving them in the air (not in the bag). The other eight instruments were also dried with a fan. At the start, in the middle and at the end of the long-term study, the instruments were always examined in the same places using three methods.

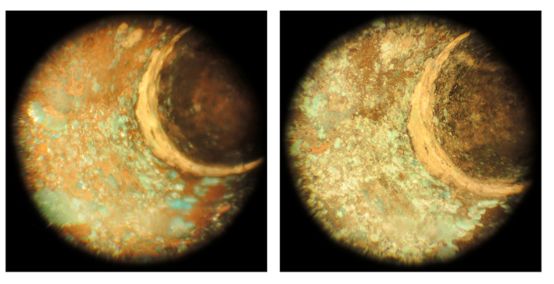

-

- Photo: David Mannes, Paul Scherrer Institute

- Breathable air was first introduced into this cornet (right) and then dried using a fan (left). Neutron images made the moisture inside visible.

- Electrochemical measurements determined the speed of the corrosive processes locally using a specially designed miniature sensor, which was pressed against the wall in the pipe with a balloon. It measured the corrosion rate at 102 points (each of which had to be found exactly). The statistical analysis showed that the instruments with a fan corroded less quickly on average than those that were not dried.

- Neutron tomography: Neutrons shine through the metal and produce a 3D model in the computer. This makes it possible to view the inside of the instrument even in inaccessible places and to detect changes from the time of the long-term study. 2D neutron images also made it possible to "film" the development of moisture inside the instrument, see image above.

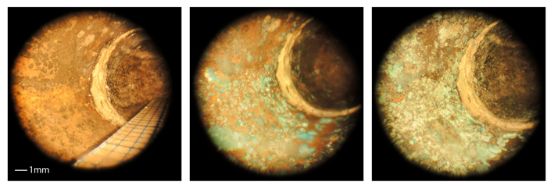

- Visual examination using an endoscope: over 1000 points in the instruments were photographed at the beginning, in the middle and at the end of the long-term study, see figure below. The local development of the different corrosion phenomena could thus be visually determined and then statistically evaluated.

-

- Photo (using an endoscope): Martin Ledergerber, Swiss National Museum

- Corrosion phenomena in the tuning slide of a tuba at the point where the tube and bend are soldered together: at the start of the long-term study (left), and the strong development after 7 and 14 months

The results of all three measurement methods showed that although drying cannot prevent internal corrosion, it does prevent it from accelerating. Like woodwind players who wipe out their instrument after playing as a maintenance measure, brass players would simply have to plug in the fan after practicing. The easiest way to do this is to use a small device that is inserted into the mouthpiece holder (available, for example, from www.serpents.ch). Warm air (hair dryer), on the other hand, is unnecessary and can cause damage. This drying method is particularly effective for instruments that are rarely played, especially those from collections, as the period of internal humidity is reduced from many days to a few hours after a single attempt at playing.

Other life-prolonging measures

Further measures could be taken to prolong the life of metal instruments: external care after playing, use of non-corrosive valve oils and lubricants, transportation in non-corrosive bags. On the project website www.hkb-interpretation.ch/projekte/korrosion The project's questions, approach and results, as well as further information and films on the development of humidity inside the building and recordings of the symposium concert (with Stravinsky's Sacre du printemps on historical brass instruments) can be found on the website.

Project title:

Brass instruments of the 19th and early 20th centuries between long-term conservation and use in historically informed performance practice