Geigerian set theory

A systematic presentation of all violin movements in six volumes that encourages new ways of practicing.

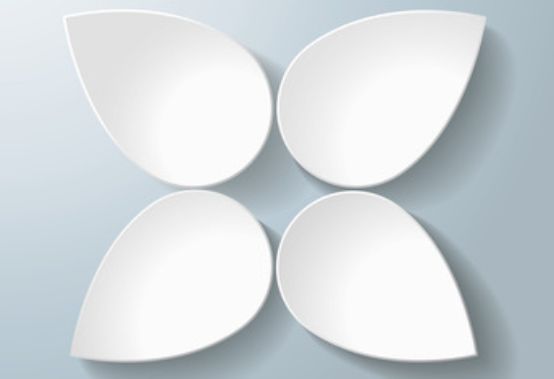

A four-part flower illustrates how the four elements of bow, string, finger and position changes alone can be combined two, three and four times. This results in the 15 parts of the systematic overview of violin technique, spread over six volumes (ED 21161 to 21166, also available as package 21161-1). Helmut Zehetmair, violin professor emeritus in Salzburg, and his former assistant Benjamin Bergmann, now violin professor in Mainz, conceived them as a "violinist's medicine chest" for practicing all the components of technique - a modern Ševčík, so to speak.

The first two volumes discussed here deal with the large "petals", not yet including the combinations. The instructions in the introduction declare that practicing technique is an artistic activity in that it should be creatively combined with rhythm, articulation, dynamics, phrasing, agogic, sound and vibrato: "True virtuosity turns technical necessity into musical virtue (lvirtus)."

The various types and articulations of bow strokes are fully described. However, bowing also has to do with physics: it is not shown that the bow is actually driven like a ferry by the string vibrations in the direction of the obtuse angle in the case of the non-perpendicular "X-stroke", which is very useful for changing contact points. When the bow is forced onto the bowing point, an admixture of high-frequency longitudinal vibrations is created. The Sautillé is not caused by a special position of the fingers, but by the fact that the bowing direction is steeper than the bowing direction thanks to the rolling of the upper arm or the swinging of the wrist. The clearly describable relationships between volume, frequency and bow position, which are a prerequisite for conscious mastery of the sautillé, are also missing.

The awareness of the seven string planes and the resulting half and whole string changes is valuable. The encouragement to legato string changes with string skipping is very commendable.

In the chapter on finger changes, many horizontal supporting fingers are recommended for stabilizing the fourth space, unfortunately not the more efficient way of setting the finger spacing ahead in the air. Why is the fingering within the diminished fourth missing from the list of fingerings? With the harmonics, it should be pointed out that you have to finger a little higher because the string is looser and therefore sounds lower than with a firm fingering in the same place. The various exercises on finger string changes and stretched fifth and sixth fingerings are valuable.

The chapter on intonation is both informative and philosophical. The combination tone is recommended for checking intonation, but why is there no mention of the resonance of the empty strings? The different types of vibrato are well described but the upper arm roll as the origin of vibrato production is not mentioned.

The second volume is a treasure trove of exercises for direct changes of position: exclusively with one finger or with the same fingers for double stops. The often-forgotten pivoting, i.e. partially moving into other positions thanks to anchoring the thumb, as Paganini apparently did, is explained and recommended.

If the subsequent volumes are as stimulating as the first two, they could inspire many violinists to think and practise in new ways.

Helmut Zehetmair and Benjamin Bergmann, Systematic Violin Technique. The building blocks of violin playing; Volume 1, Bow, string and finger changes, ED 21161; Volume 2, Direct position changes, ED 21162; € 18.99 each, Schott, Mainz 2013