Pluralism instead of demarcation!

An anthology presents sociological approaches to music.

There were times when musicology concentrated on biographies and analyzing works. It was not until the 1970s that the methodology expanded. To put it bluntly: the "trappings" became more important. This included institutional conditions, considerations of reception aesthetics, the cultural environment in which music thrives, as well as the further development of those approaches that were essentially based on Theodor W. Adorno. Under the auspices of general specialization, it is not surprising that various research areas soon split off: Today there is music psychology, empirical musicology, systematic musicology, music anthropology and, of course, music sociology.

The volume published by Laaber-Verlag Sociology of music does not claim to clarify the question of what sociology of music means. Right in the preface, the editor Volker Kalisch makes it clear that the sociology of music does not have "the unique question, the guiding interest, the decisive knowledge intention, about the method that distinguishes it from other scientific disciplines and subjects, about the strategy of mediation or via the clarifying system of representation and designation" (p. 10). With such a rigid renunciation of the singular, there is no other solution than to provide an inventory in the form of various branches of research. 20 authors do just that. They deal with subtle questions of scientific theory such as the distinction between the sociology of music and the sociology of music, the nature of musical rituals, insights into interaction patterns and communication structures. In short, the subject is defined in the sense of the American ethnologist Clifford Geertz: through the refinement of a discourse, through the presentation of selected subject areas that can at least evoke an image of what the sociology of music means, or rather could mean.

There are two reasons why this picture remains vague at the end of the reading: As in any human science, things are not as straight to the point as they are in the natural sciences or in the case of the motivic-thematic analysis of a Bach fugue. In addition, the relatively young discipline of music sociology is still searching for foundations. Criteria must first be established for each study, and it is worth noting that methodological borrowings from the much more established discipline of sociology are few and far between. On a more positive note, there are studies that have not yet come to the attention of "classical" musicology. Although music - worldwide - is inextricably linked to rituals, "classical" musicology has been speechless in the face of this difficult subject matter, whereas Raimund Vogel, Eckhard Roch and Wolfgang Fuhrmann offer convincing approaches in this anthology. The authors' global approach with clear references to ethnomusicology and anthroposophy is commendable - and at least justifies the existence of music sociology, which could simply see itself as an expandable discipline. Musicology as a whole could benefit greatly if its sub-disciplines were to complement each other in the sense of methodological pluralism. In any case, further trench warfare - which is certainly alluded to in the volume - would be fatal. They would further weaken the already ailing discipline of musicology as a whole.

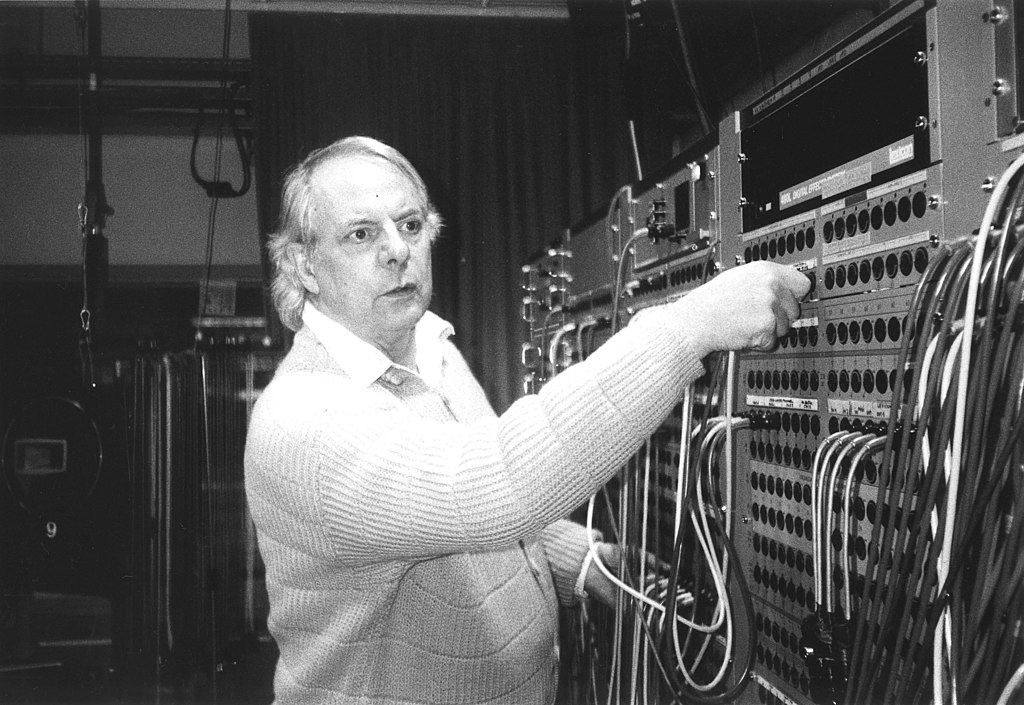

Music Sociology, edited by Volker Kalisch, (=Kompendien Musik Bd. 8), 303 p., 15 ill., € 29.80, Laaber-Verlag 2016, ISBN 978-3-89007-728-4