From the beginnings of European polyphony

The "Musica enchiriadis" was last translated 140 years ago. A contemporary, explanatory new translation of this important treatise is therefore very welcome, but also a difficult undertaking.

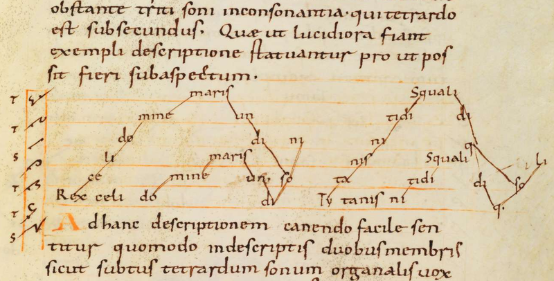

The Musica enchiriadis, often quoted but only known in detail to experts at best, is one of the most important and probably most successful treatises in the history of Western music. Written in the late 9th century, perhaps by an abbot named Hoger von Werden who died in 906, the "Handbuch" has been handed down in around fifty manuscripts. It explains the tonal system together with its own notation, first in monophonic, then in polyphonic form up to the organum. What may seem "primitive" is evidence of enormous musical progress, and so it makes sense that the work is now - after 140 years - available in a new translation.

Three insightful introductions on the reception of antiquity (Michael Klaper), the theory of monophony (Andreas Traub) and the theory of polyphony (Petra Weber) provide an introduction to the musical thinking of the time. Philological considerations are less central than the attempt to make this text accessible to us today.

It is best to read the treatise three times: the German text including the footnotes, which can be compared with the Latin original - and the explanatory introductions. In this way the Musica enchiriadis in their singular novelty, also in their complexity, which must be translated and conveyed today. Because the words were understood differently. The Latin "vis", for example, is of central importance: it says that one should distinguish and recognize the forces of the individual modes: Koblenz musicologist Petra Weber chooses various translations for this (force field, influence), thus dissolving the uniform terminology. This is entirely appropriate, but also points out how tricky translation is. Our modern terms don't quite work and can even distort the old text.

Sometimes the translation becomes an egg dance, one constantly feels the inhibition to use certain modern terms, and perhaps it would have been useful to offer both a literal and an approximately modern translation. Occasionally, the editors are also overly cautious with "modern" explanations. Of all things, the unique Dasia notation - in contrast to the MGG article - is not translated into modern notation; some points in it that are difficult to understand are therefore not mentioned. At such moments, the musicologists involved are too much experts and think little of the interested layman. Certain explanations of words seem detached, and a footnote such as: "There could be connections with the concept of nomos, but we are not pursuing this here." may at best be useful for the connoisseur, but it annoys the reader. Similar details and omissions, as well as some inadequately coordinated translations between the authors, testify to the fact that the material is not conveyed with enough thought. A pity, because the whole thing is highly exciting and deserves wide attention.

Musik enchiriadis, Latin and German, translated and edited by Petra Weber, 147 p., Fr. 31.60, Wilhelm Fink, Paderborn 2016, ISBN 978-3-7705-6054-7