The Swiss flamenco

It is hard to imagine anything more Spanish. But it was in Switzerland of all places that a flamenco culture of international importance developed, which is now being forgotten.

Well-known composers of all nationalities were inspired early on by the exoticism of an imaginary Spain. From Scarlatti to Liszt and Rimsky-Korsakov to Debussy and Ravel, their music has been influenced by such elements.

This phenomenon has also been observed in Switzerland since the 19th century: Joachim Raff, Hans Schäuble or Armin Schibler wrote several plays in the Spanish style. Spanish immigration to Switzerland began at that time. It intensified during the world wars and the Spanish Civil War. Although official Switzerland did not approve of the use of war volunteers on the Republican side, visas were issued for Republicans willing to leave the country. The Spanish Manifesto, read out by Hans Mühlestein on Basel's Barfüsserplatz on May 1, 1937, speaks for the close ties between the populations of the two nations. Language was by no means an obstacle to cultural exchange: the Swiss Enrique (Heinrich) Beck is regarded as the first translator of Federico García Lorca. In 1944, the immigration police approved the first performance of the play Blood wedding in German-speaking countries, shortly followed by those of Bernada Alba's house. Paul Burkhard composed the music.

Distrust of the "Spanish"

Wherever Spanish musical elements appear, Spanish dance is not far away. Curiously, however, the first representative flamenco figures did not come from Spain: dancers such as Petra Cámara, Lise Bonnet and Fanny Elssler had already been touring Europe since 1850 with their exotic, partly invented flamenco steps. Even the first flamenco legend La Argentina launched her career and lived outside of Spain.

From the First World War onwards, Switzerland experienced a real wave of immigration of great artists who left their mark. Music and dance received important impulses. The symbiosis between Spanish dance forms and local expressive dances was particularly strong. An extremely interesting cultural event in this respect was the First Swiss Dance Competition in 1939 as part of the National Exhibition in Zurich. It attracted the most famous dancers in Switzerland, such as Suzanne Perrottet, Lilly Roggensinger and Dora Garraux.

The media response provides valuable evidence of this: The NZZ wrote that it was understandable that "(...) the female competitors turned to the Spanish dance style, which feigns sensual temperament with its loosening of the hips, strong tapping steps and coquettish fire in the eyes", while the newspaper National law reacted disrespectfully: "(...) the use of important music for mood-making and rhythmic slavery is to be completely rejected; conversely, neither the music nor the dance is served by imitating strict musical forms in dance. Among the subjects, Spanish was conspicuously popular, often shown in beautiful solutions." At the time, few people understood that Switzerland could have supported and developed a potential dance and music heritage.

A Swiss woman spreads flamenco around the world

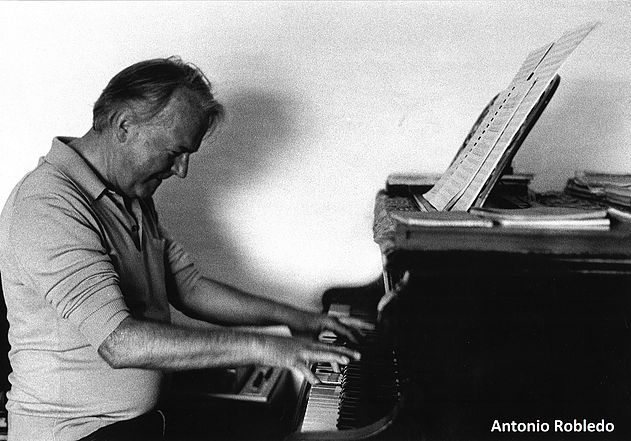

Alongside well-known dancers, a young Susanne Looser (later Susana Audéoud) performed there. She was interested in flamenco. She later went to Spain, where she founded her successful company with José de Udaeta. In their search for musicians, they engaged a young man, Armin Janssen, who was continuing his piano studies at the time and was fascinated to join in. He soon emerged as the flamenco composer Antonio Robledo.

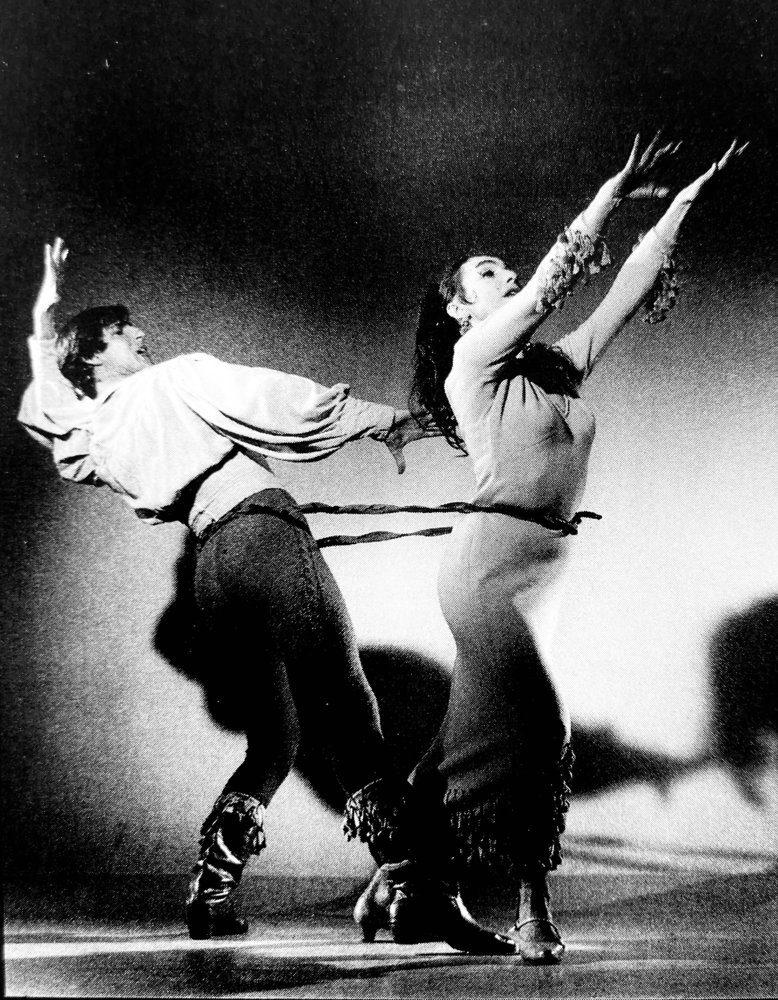

First in Spain, then worldwide, they conquered the stages. Flamenco was performed for the first time in many countries. Their work is of great ethnomusicological value: they traveled through Spain with recording equipment in their suitcases. They discovered and supported great flamenco personalities who played an important role in the history of singing: Carmen Linares, La Talegona (who until then had lived in great hardship as a cleaner), Sernita (we have them to thank for the only existing recording of his voice) and, among many others, Enrique Morente. The three of them began to develop their own concept of a ballet danced in flamenco style.

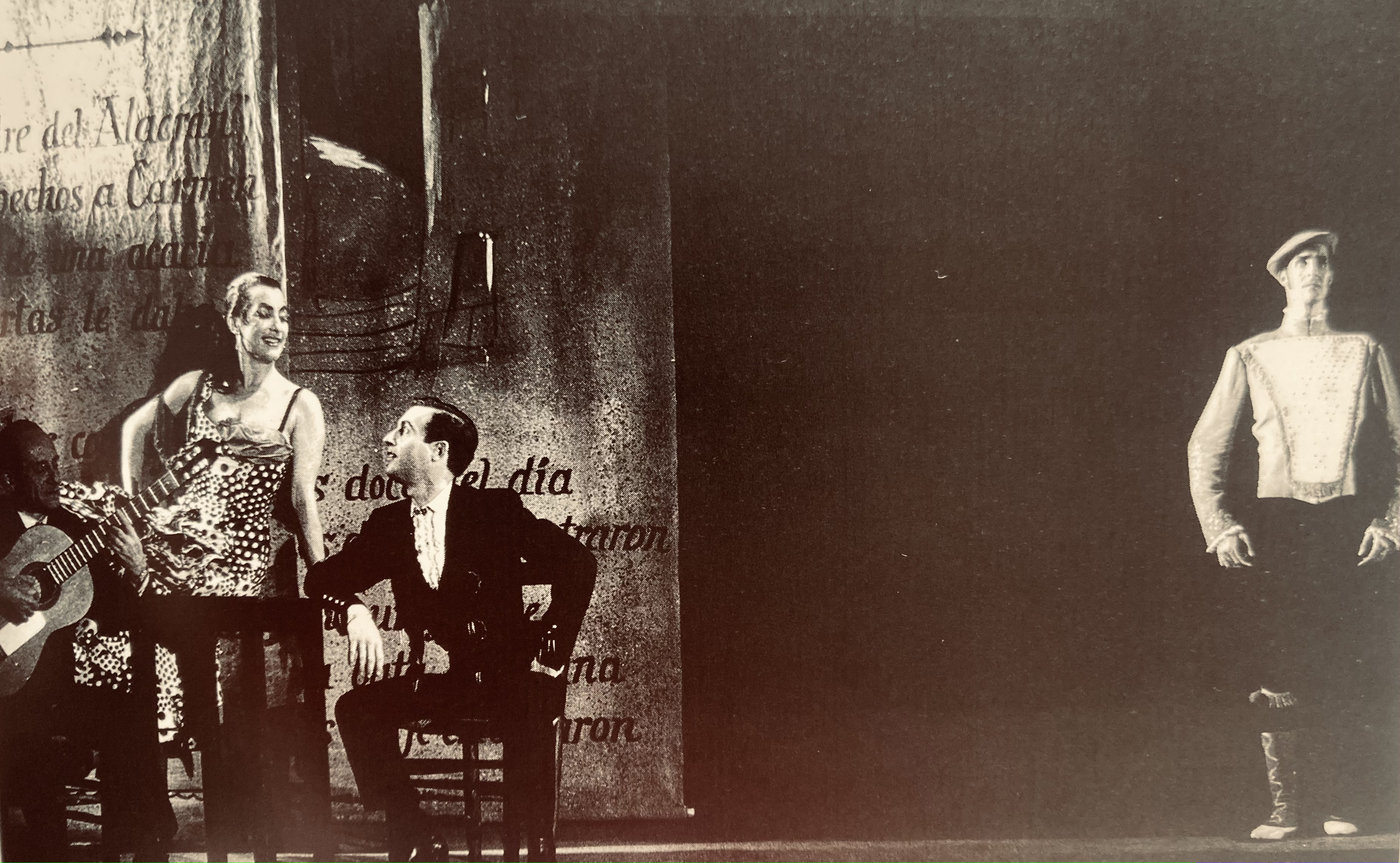

La Celestina (1966) was successfully performed and the composition was sold on LP. The joy of experimentation also gave rise to the choreography and further recording produced in Switzerland in 1985: Obsesión. The unusual organ sounds and Morente's powerful voice won over the experts. The public had a different opinion of their symphonic collaboration: At the famous Bienal de Flamenco, they were described as art criminals. Twenty years later, however, they were celebrated as the holy saviors of pure flamenco. Important flamenco artists who worked with them still speak lovingly and with great respect about Armiño and Susana today.

Weighty legacy, big names, little resonance

It was not only in music that they left their mark: Susana's innovative legacy brought about a renewal and consolidation of flamenco ballet, which even influenced legends such as Antonio Gades and prompted him to adopt the concept with his company. Armin and Susana worked as teachers in opera houses, universities and ballet companies. Their collaboration with the Ballet of Toronto was captured on film by Cynthia Scott and even won an Oscar for best short documentary in 1983. Their synthesis with Spanish culture was so successful that they were mistakenly celebrated in various media as Spanish flamenco artists.

In Switzerland, Susana played an important role in the professionalization of dance. Her heirs became world-famous: Brigitta Luisa Merki led the Flamencos en route company for forty years, developing Susana's concept further and celebrating successes at home and abroad. Nina Corti, La Carbona and Bruno Argenta became important dance artists. Teresa Martin became an internationally recognized dancer and choreographer. Robledo dedicated many compositions to her.

Teresa's father, the composer Frank Martin, was also swept along by Susana's and Robledo's storm: from then on, his pieces showed tendencies of flamenco music (e.g. Fantaisie sur des rhymes flamencos, 1973, or Trois danses, 1970). Teresa created choreographies and danced them on stage. The pianist Paul Badura-Skoda or Ursula and Heinz Holliger played at the premieres. Other composers such as Joaquín Rodrigo and Rolf Looser were enthusiastic and also composed for her.

The fact that this extraordinary chapter in Swiss cultural history has been forgotten is probably not only due to financial cutbacks in the dance and music sector: The idea that a certain style does not fit in with the identity of the original Swiss - i.e. that it seems "Spanish" to us - certainly also plays a role. Such prejudices in the reception of Swiss cultural movements contribute to this unique cultural heritage disappearing from the stage and from our consciousness.

*

Isora Castilla is a pianist and musicologist. Her several years of research at the University of Bern will soon be published as a book in Spain and Switzerland.