Love letters and philosophy

Vocal cycles with orchestra from Heinrich Sutermeister's early and late creative periods.

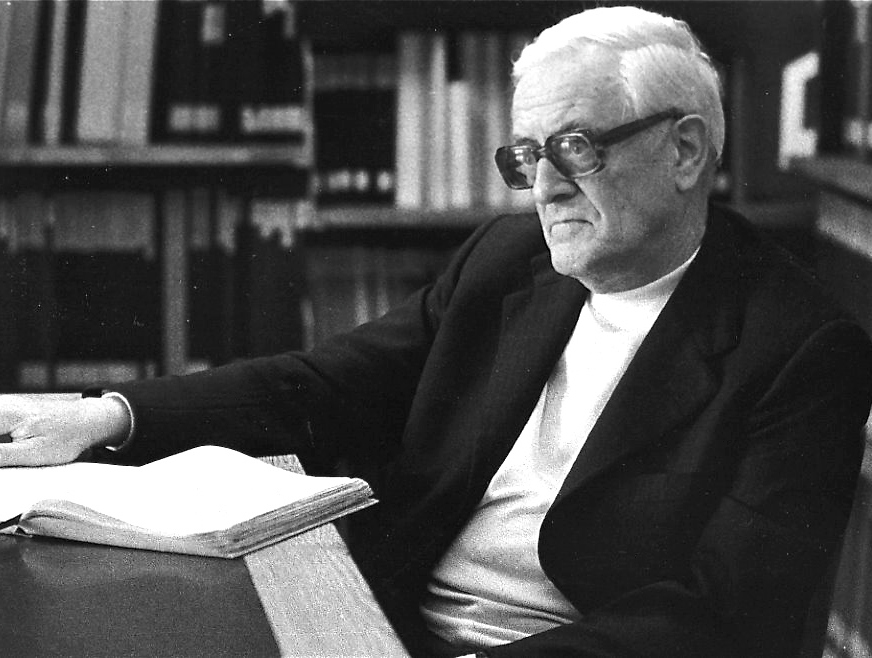

In an article on Heinrich Sutermeister, in which she characterizes the composer quite clearly as a Nazi collaborator, musicologist Antje Müller writes that when considering "conformist" music from Germany between 1933 and 1945, it is not the "music, which is mostly poor anyway, that should be examined", but the reception, as the music alone would hardly convey all the associative accessories. This does not do justice to the music of the composer, who was born near Schaffhausen in 1910 and died in 1995 in his adopted home on Lake Geneva.

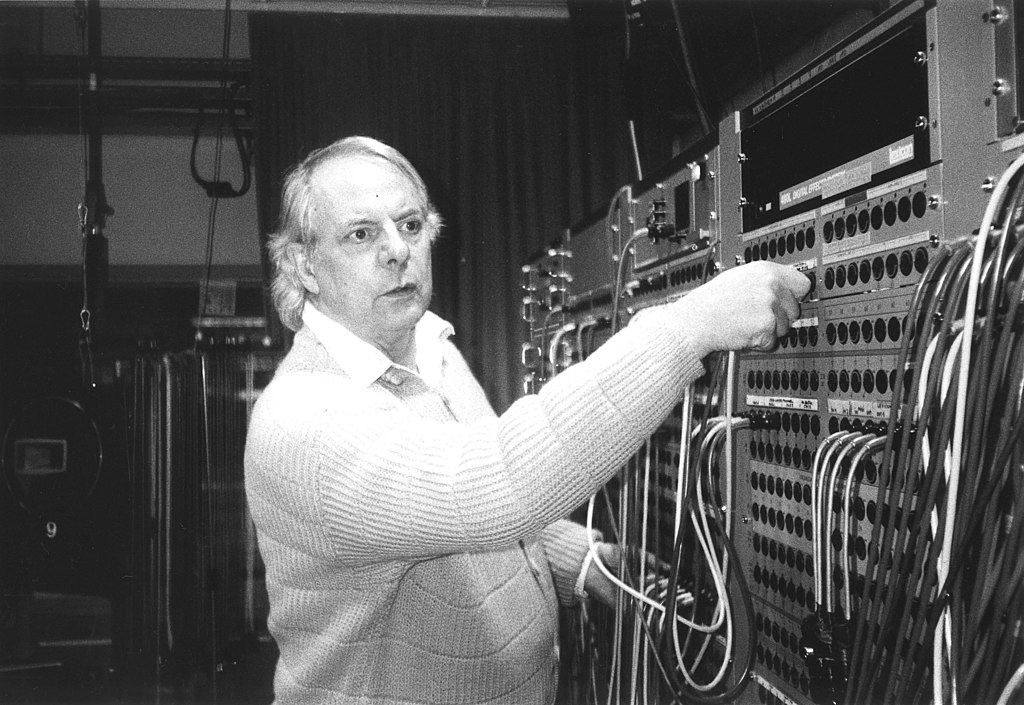

The fact is, however, that Sutermeister, who had studied in Munich with Walter Courvoisier and the arch-conservative Hans Pfitzner, among others, and whose friends included Carl Orff and Werner Egk, who were very close to the Nazi regime, seemed blind to life and politics in Germany. Two of his operas were successfully premiered in Dresden in 1940 and 1942, while a third, written for Berlin, could only not be performed due to the events of the war. It seems strange that the booklet of the new Toccata Classics CD makes no mention of this problem, as Othmar Schoeck is regularly criticized for his lack of distance from the National Socialist state.

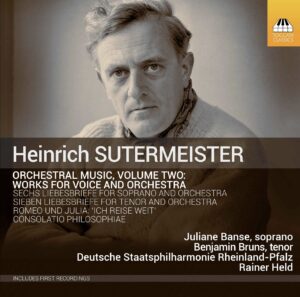

The CD contains Sutermeister's great vocal cycles as well as an aria from the opera Romeo and Juliet (1940). There is no question that the composer understood his craft and was also able to develop a personal style based on late German Romanticism and remaining true to tonality and conventional instrumentation, with the harpsichord adding a few unusual touches of color. It is astonishing that the Seven love letters for tenor and orchestra from 1935 does not sound worlds apart from the Six love letters for soprano and orchestra from 1979. The choice of texts is actually original: they are love letters from the 16th and 18th centuries by mostly well-known personalities and poets who describe very different moods. The problem is the abundance of text, which is not always comprehensible, at least without a booklet in hand, and also seems a little long-winded. The same applies to the Consolatio philosophiae for high voice and orchestra on Latin texts by the Roman philosopher Boethius, which was written in memory of Ernest Ansermet and premiered by Peter Schreier in Geneva in 1979.

Despite competent interpretations by the soprano Juliane Banse, the tenor Benjamin Bruns and the Deutsche Staatsphilharmonie Rheinland-Pfalz under the direction of Rainer Held, the CD is not a fiery plea for renewed concert performances of these works.

Heinrich Sutermeister: Orchestral Music Vol. 2, Works for Voice and Orchestra. Juliane Banse, soprano; Benjamin Bruns, tenor; Deutsche Staatsphilharmonie Rheinland-Pfalz; Rainer Held, conductor. Toccata Classics TOCC 0608