(Giovanni) Henrico Albicastro

If the first German-language "Musicalisches Lexicon" by Johann Gottfried Walther (1728) is to be believed, the Baroque composer Albicastro (1662?-1730) was "a Schweitzer". However, no proof or evidence to the contrary could be found for centuries.

Documents that only came to light this year now most probably point to Klosterneuburg near Vienna as the place of origin. They were found by the Dutch philosopher and genealogist Marcel Wissenburg, who was interviewed in the Music newspaper of October/November 2016 (p. 10 ff) reported on this. However, it is still unclear where the composer received his musical training - he was apparently a virtuoso violinist - how he came to the Netherlands, the country in which he spent most of his life, why he wrote most of his works during the busiest period of his military career and why he then suddenly stopped composing.

Otmar Tönz, professor emeritus and former head physician at the Lucerne Children's Hospital as well as a passionate music researcher, began searching for Albicastro's place of origin in 2006. In 2010, together with the musicologist Rudolf Rasch, he reported in a Article of the Swiss Music Newspaper about the research (SMZ 4/2010, p. 19 ff.)

Rudolf Rasch and Otmar Tönz have also summarized the detailed research results of the ultimately fruitless search in a 65-page publication: Otmar Tönz, Rudolf Rasch, Henrici Albicastro, 2nd, revised and expanded edition. [University of Applied Sciences for Music], Lucerne 2011.

Albicastro composed 51 sonatas for solo violin (with b.c.), 2 for viola da gamba, 60 trio sonatas and 12 concerti (quartets); also the soprano cantata Coelestes angelici chori. Of the 11 sonata collections, 2 are completely lost and 2 partially lost, Opus II presumably only since the Second World War.

Short biography of Albicastro and small exhibition of his work

Author: Otmar Tönz (1926-2016)

State of knowledge 2015

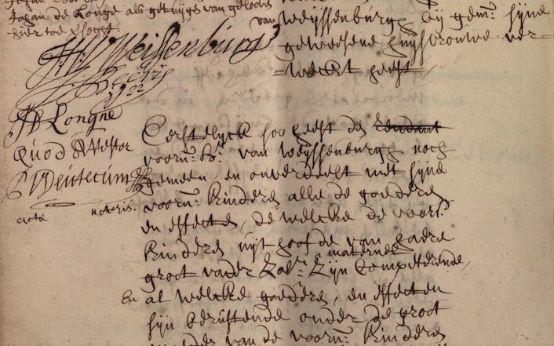

Shortly after the middle of the 17th century, a boy named Joh. Heinrich Weissenburg was born in the European cultural area, albeit without an official entry in a baptismal register, i.e. posterity knew neither his mother's name, nor his father's profession, nor the date of his baptism, nor the place of his birth. It is not from records, but from the further course of his retrospectively recorded life story that we learn that this boy possessed an extraordinary talent: he mastered the violin at a high level at an early age and also learned music theory and composition with ease.

The first and only document we have is from the young Weyssenburg, already an adult, who was appointed Musicus Academiae at the University of Leyden in the Netherlands. It is not known how he ended up in the Netherlands. The above-mentioned university document contains a very important fact in addition to his employment: He describes himself as Viennensis (from Vienna) in terms of origin. Since then, countless Albicastro fans have probably searched the ecclesiastical and secular records in Vienna, but - like us - without success.

Confusion was then caused by the later appearance of the lemma "Albicastro" in the first German-language music lexicon by J.G. Walther (1728): "Albicastro (Henrici) ein Schweitzer, Weissenburg eigentlich genannt ... " interest now focused on Switzerland, until today. His works were edited in the series "Schweizerische Musikdenkmäler" and financed by the Swiss Confederation. The first scholarly works were also produced in this country. The Swiss violinist and Bavarian chamber musician Walter Probst copied the entire work, which was not yet printed at the time, in very beautiful handwriting and at the same time wrote out the bass. Finally, in the 1970s, Prof. Kurt Fischer discovered the solo cantata Coelestis angelici chori at the Brussels Conservatory.

All we know about Albicastro's childhood and youth is that he was a precocious musical genius with regard to playing the violin and composing monophonic and polyphonic sonatas, predominantly in the Italian style (modeled on Arcangelo Corelli). Unfortunately, we know nothing about his schooling and musical education. He probably only attended Latin school (and Italian lessons) at the lowest level; his orthographic and grammatical errors are too frequent, e.g. the use of the genitive for his first name.

Military and musical career

In the Netherlands, Weissenburg also joined the army, where he rose ten ranks in a long and successful career, from non-commissioned officer to cavalry captain. He served in Dutch regiments that were deployed in the War of the Spanish Succession. From 1706 he signed his musical works exclusively as Henrici Albicastro, his official and private papers from 1686 as (Johan) Hendrick van Weyssenburgh.

At around the age of 40, there was a profound break in his life: he put aside his violin and concentrated exclusively on his military career in the mounted troops. This change of career can probably be seen as an expression of his ambition. A group of Swiss engravers see his personal dream place on the "Feldherrenhügel".

Family circumstances

In 1705 he married Cornelia Maria Coeberg, a merchant's daughter from Grave, a fortified and garrison town on the Meuse. After the birth of his first child, they set up their own household in the same street (Klinkerstraat), diagonally opposite her parents. The first child was Gerhardus Alexander, who also followed in his father's footsteps and embarked on a military career, but unfortunately died at the age of 22. This was followed by daughter Johanna Allegundis, efficient, hard-working and intelligent, who married the estate manager of the Princely House of Hohenzoller-Sigmaringen - Petrus Johannes Hengst - and left behind a large family whose last descendants are still alive today.

He was followed by another boy, Johannes Michaelis, who, like Gerhard, had also completed Latin school with the Carmelites in Boxmeer. He finally succeeded in his military career. But despite his ten children, the von Weissenburg line dried up among his grandchildren, so that this family died out in the Netherlands or emigrated. Finally, his fourth daughter Everdina Alexandrina followed. We only have a baptismal entry for her. She was born in Grave in 1713 and joined the Carmelite Order as a nurse in 1734.

There is no indication that his wife died. In any case, the 61-year-old widower married a second time on February 15, 1722. The chosen one was Petronella Baronessa Rhoe d' Oppsinnigh, a baroness who might have been able to fulfill his dream of a military mound, but whose lifestyle far exceeded the knight's financial means. First of all, two horses plus a carriage and stables had to be purchased. The luxurious social life and other costs not only led to poverty, but also to a large mountain of debt, which the children from his first marriage and the widow from his second marriage had to pay off.

Compositional work

If Albicastro put down his violin when he entered the military schools, this does not apply to his composition notebook. Paradoxically, this was when his most musically productive phase of his life began. It is almost unbelievable that in the years of his military training and first career steps he composed exactly 100 sonatas, mostly in four movements, in all major and minor keys, some of them technically very demanding: full of double stops and extended fugal movements. The writing alone is a huge task. For others, 100 sonatas are a life's work. If we add the earlier, later and lost works, we arrive at around 130 compositions, mainly sonatas.

One special form should be emphasized, the Folia, a theme with "omitted" variations. Corelli also wrote a folia; op. V / No. 6. In deference to his spiritual teacher, Albicastro also includes his as op. V / No. 6. A comparison reveals: The Roman writes according to the rules of the art, keeps to the historically prescribed bar and movement numbers, lively but not exuberant, artistically very clean. Albicastro's writing is rather wild, with movements of different lengths, sometimes very high tempi, emotionally stronger outbursts and a roaring finale in the final bars.

Albicastro's only vocal composition is Coelestes angelici chori, a sacred solo cantata for high voice, strings and basso continuo. Perhaps Albicastro's last piece of music? A beautiful vocal work that opens with a brilliant, richly colored main movement. This is followed by an incredibly beautiful recitative (almost only known from Bach), followed by a delicately flowing adagio in which soft solo violins weave around the singing. The cantata then concludes with a festive Hallelujah.