Review with phantom pain

A conference on "Music Discourses after 1970" at the Bern University of the Arts.

The range of content was broad, thanks to the variety of topics and the international focus. Although one focus of the conference (March 23-25), which was conceived by Thomas Gartmann, Head of the Research Department at Bern University of the Arts (HKB), was on Switzerland and the Tonkünstlerverein (STV), there were also numerous contributions on developments in Western and Eastern European countries, South Africa and the USA. Gender issues were also discussed. The result was a conference rich in perspectives, with a wealth of information and points of view that stimulated productive further thought.

The key points were marked by two presentations at the beginning and at the end. Jörn Peter Hiekel began by taking a critical look at the one-sidedness and dichotomies in the avant-garde's discourse on progress since the 1950s, dedicating a special chapter to Adorno and his lasting influence. However, he did not fall into the trap of the usual black-and-white painting of the time - here the progressives, there the reactionaries - but spoke out in favor of an unbiased but historically informed way of thinking.

The antithesis was provided by the ideologically narrow final presentation by Jessie Cox, a Swiss composer, drummer and educator with Rasta braids, who has dedicated himself to the fight against the cultural hegemony of the white man and threw around a lot of empty identity politics terms. Starting with the unfortunate "diversity" theme of the Lucerne Festival 2022, he lectured via Zoom from New York for three quarters of an hour on the ineradicable racism of the Swiss and apostrophized their media, above all the NZZas mouthpieces of an unreflected anti-blackness. Cox will now be performing live at the Lucerne Festival in August. So entertainment is guaranteed.

Controversial issues excluded

The change in discourse as a historical process has only occasionally been explicitly addressed. What has become of Habermas' discourse ethics in musical terms, what does Foucault's Ordre du discours about today's music business? Such explosive questions were beyond the scope of the assembled musicologists' interest. The far-reaching changes in music criticism were also only addressed in passing and from the high horse of musicology. The presentations mostly revolved around concrete phenomena and projects, aesthetic trends and institutional problems. This resulted in a panorama of quite critical snapshots, but a presentation that would have placed such detailed aspects in a larger temporal horizon would undoubtedly have been an asset. For example, two major trends of the last fifty years that have also had a significant impact on music were not discussed at all or only to a limited extent: the increasingly apparent end of Eurocentrism and the media revolution.

Extinguished lighthouses

As far as the media are concerned, Pascal Decroupet examined the influence of digitalization on composing using the example of French spectralism, and insights into the reality of television were provided by Thomas Meyer, who recalled the productions of Armin Brunner with Mauricio Kagel, and Mathias Knauer, who demonstrated how experimental music film productions have been set to zero over the years in German-speaking Swiss television. He wished for a return to a politically emancipatory approach to the medium, as Walter Benjamin once imagined it - a laudable idea, but one that is pure utopia today in the face of a media industry controlled by global capital interests.

Gabrielle Weber presented a different model of cultural promotion through the mass medium of television with two series of music films produced in 1970 for French-speaking Swiss television and in 2001 for DRS. While the older production placed music-making in a socio-cultural context and showed, for example, the composer André Zumbach working with children conducting, the ten films made by director Jan Schmidt-Garre on behalf of DRS and STV focused entirely on the composers and their works. With the release on DVD, a new medium at the time, the films from 2001 reached an audience that went beyond just television viewers. The juxtaposition of the two series revealed something of the change in perspective that has taken place in the arts over the last thirty years.

In addition, there was still close collaboration at the time, especially between Radio DRS and the Tonkünstlerverein. This is the subject of a research project reported on by Stefan Sandmeier and Tatjana Eichenberger. The difference to the present is striking: today, television stations see themselves primarily as a distribution medium, they buy finished productions or at best participate in co-productions. With the exception of ratings-rich recordings of mass events or star portraits, music films have migrated to special-interest channels such as Arte, 3sat and global satellite and internet channels.

These realities are irreversible and there is no point in lamenting them. In this respect, Peter Kraut performed a dialectical tightrope walk with a mixture of self-irony and precise socio-cultural analysis, but without nostalgia for the "golden age" of the event he curated. Tactless Bern and Key Bern looked back on. They were beacons in the alternative music scene of the late 20th century.

Music on the party's tightrope

Two major topics caught the eye. On the one hand, there were the retrospectives by Eastern and Central European speakers on music policy in the former Eastern Bloc. Lithuanian Rūta Stanevičiūtė's observations on how national traditions were made subservient to the system-stabilizing doctrine of socialist realism under communism found a parallel in Jelena Janković-Beguš's (Belgrade) presentation on the cultural policy of non-aligned Yugoslavia. Using the central figure of Nikola Hercigonja as an example, she demonstrated the politically intended felt between the party and artistic creation. The composer and functionary Hercigonja was built up into a musical national hero by the party and the media controlled by it, with the result that his pompous aesthetics still resonate in Serbian music today. Today, the avant-garde movement to break away from this legacy also includes the Quantum Music Project from Belgrade, whose seven members practice a refreshing combination of musical experimentation, technical curiosity and the search for new social models.

The funny barracks

Musical life under socialism was by no means uniform. Away from the official institutions, musicians repeatedly tried to use the narrow scope for alternative practice. They were kept on a long leash by the party, such as the group Neue Musik Hanns Eisler in the GDR, whose members were also guests at the Künstlerhaus Boswil on several occasions from the 1970s onwards. Or where control was perforated, as in Hungary, which was envied as the "funniest barrack in the socialist camp", artistic nuclei emerged with long-term effects even after 1989 - one example is the career of the young Peter Eötvös. From 1956, the Warsaw Autumn Festival in communist-resistant Poland was a center of almost magnetic attraction for all free-minded musicians; here, East and West could meet for open dialogue. Fortunately, the voices from the former Eastern Bloc were given a lot of space in Bern - which is by no means a matter of course for Western European musicology.

The STV, a memory neurosis

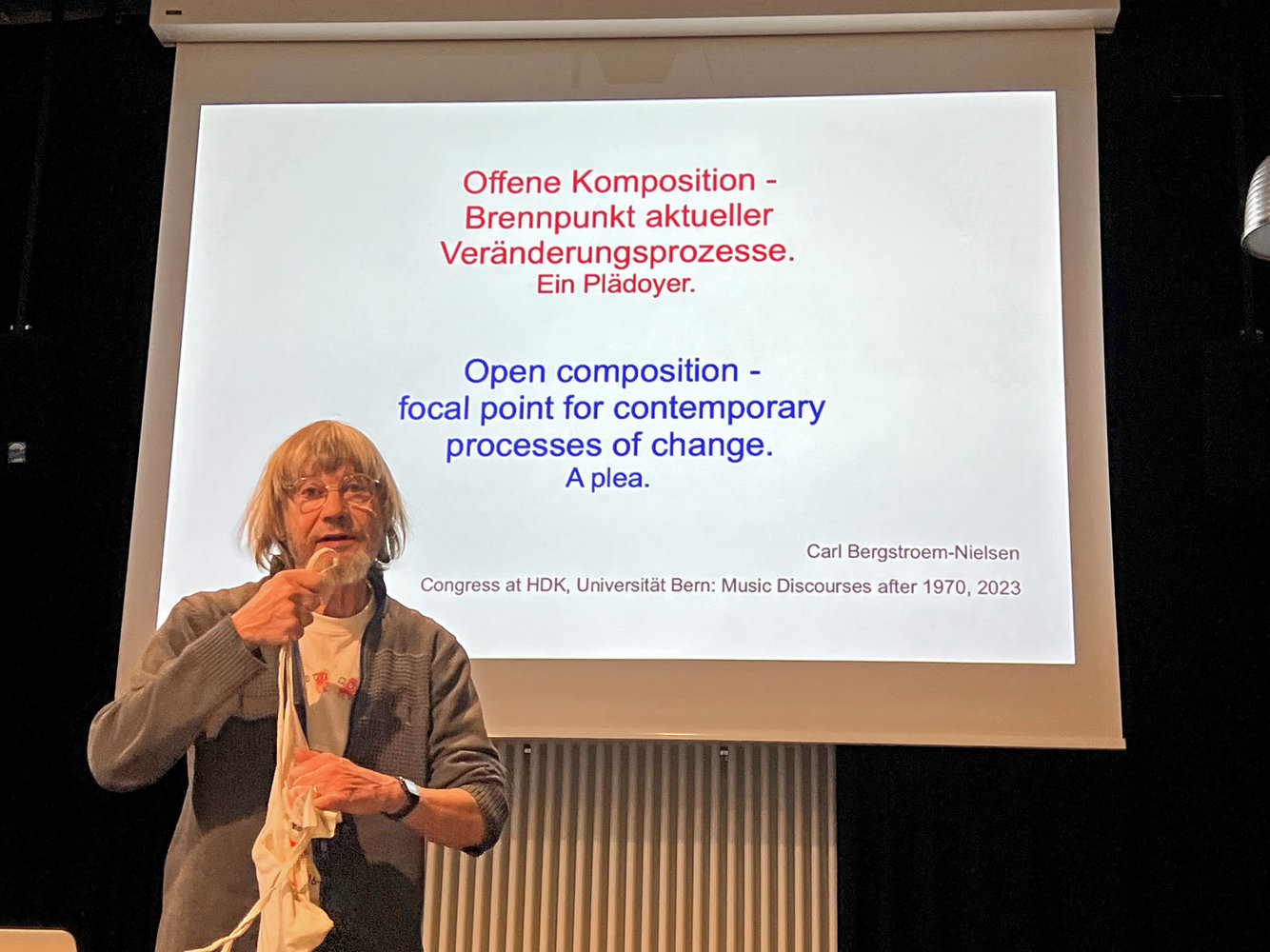

As is well known, the history of the STV is the subject of a National Fund project, which now also provided the framework for the Bern conference. Consequently, the second major topic revolved around the STV. It is remarkable that this happened in close connection with the discussion about free improvisation - apparently this is a bundle of problems that is still capable of arousing music policy neuroses. What is even more remarkable is that the institutional decline of the STV and its journal Dissonance/Dissonance This trend ran parallel to the emergence of free improvisation, which was widely discussed in the press, became a popular object of cultural promotion and finally became an institutionalized genre at universities. These tendencies towards consolidation were counteracted by the appearance of Carl Bergstroem-Nielsen (Copenhagen). His "lecture" consisted of a scenic-musical performance of indecisive searching and accidental finding, interspersed with sudden ideas - a welcome break.

After the extensive discussions about improvisation and its significance in musical life, an outsider was forced to think: Did this Swiss variety of deconstructivism and the negation of the traditional concept of the work act as an aesthetic ferment that accelerated the disintegration process of the STV on both a discursive and personnel policy level? With the dissolution of the concept of work, the influence and commitment of the long-serving active members in club life also dwindled - fixed structures were now frowned upon. The late inclusion of improvisers in the STV's governing bodies was just one outward sign of the creeping aesthetic paradigm shift.

Defeatism and structural decay

The plug was ultimately pulled on the STV due to the funding policy of the Federal Office of Culture, which no longer provided funding for artistic activities. Association members and committees turned a blind eye to the impending fiasco. In his presentation, Thomas Gartmann described the long, drawn-out countdown with merciless clarity. Based on this assessment, the disaster appears to be a textbook example of institutional failure and, in view of the passivity of the members, a beacon of democratic politics. The reasons, one may assume, are to be found in the minds: A loss of values, a lack of direction and, consequently, inaction in the face of a changing reality that people did not want to acknowledge. In their act of self-destruction by letting things happen - the whole thing evokes associations with a Marthaler production - those responsible at STV proved themselves to be truly avant-garde. They were way ahead of their time, as a look at the current Credit Suisse case confirms.

Incidentally, in the discussions on this dreary retrospective, the disappearance of musical discourse was lamented in unison and the faded Dissonance/Dissonance dedicated a wreath. That the SMZ could be a forum for such a discourse did not occur to anyone. It was not even mentioned. But perhaps those present sensed that the time for the old discourse was over. But nobody yet knows what a new one should look like. Perhaps a look at today's reality could help.

The "Schweizer Musikzeitung" is media partner of the conference "Music Discourses after 1970"