Richard Wagner and Heinrich Schenker - two aesthetic paradigms

According to Heinrich Schenker, a composition reveals itself through its structure. For Wagner, on the other hand, a work reveals itself in the experience of its expression.

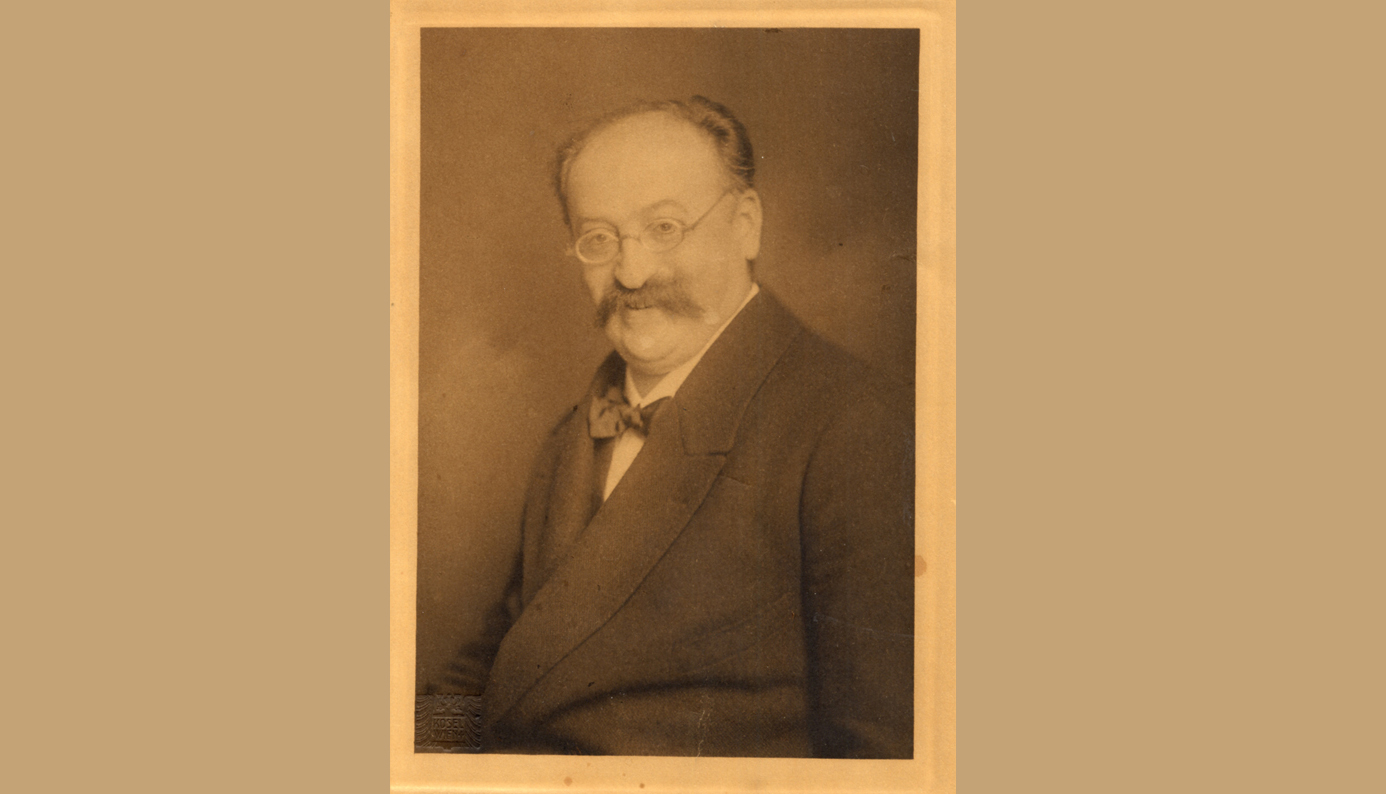

They were both convinced of the solitary greatness of German art - Richard Wagner, this year's jubilarian, and Heinrich Schenker. But that is pretty much all that connects the two. The closing words of Hans Sachs ("honor your German masters") from The Mastersingers of Nuremberg certainly met with Schenker's undivided approval, but he was suspicious of the Bayreuth master's music. While the one recovered brilliantly from the Nazis' appropriation, Schenker's theory has not yet regained a foothold in German-speaking countries after the war. Unfortunately!

Example Beethoven

Using the beginning of Ludwig van Beethoven's Symphony No. 5 in C minor op. 67 as an example, Schenker explains the difference in aesthetic position between himself and Wagner. The scholar, who has put aside his own compositional work in favor of developing his theoretical approach, rewrites the pieces in his analyses, as it were. This activity itself can therefore be seen as a creative act. He starts from a primal movement or a primal line that holds together the works of the major-minor tonal epoch on a background level. His analyses thus develop all the phenomena of a piece from a primal cell, showing how each sounding motif is connected to this unifying primal movement. The method of representation is thus deductive, working its way up from a background via a middle ground to the events on the surface. Goethe's concept of the Urpflanze is closely related to Schenker's designation of the Ursatz.

In his analysis of the above-mentioned symphony in issue 1 of The will to sound the Viennese theorist explains that he does not regard the first two bars (g' g' g' e flat') as the motif of the first movement, as is usually the case, but rather the community of the first five bars. Only with the repeat set one second lower (f' f' f' d') do we have the complete nucleus. This distinction may seem sophistical at first glance, but on closer inspection it is essential. By considering the first five bars as a unit that can be divided into two partial moments, the idea of the motif is placed on the secondary motion from e flat' to d'. In the other approach, in which the first five bars consist of two added elements, attention is inevitably drawn to the quaver motion with the subsequent downward leap of a third. This difference is of decisive importance for the hermeneutic method. Schenker then shows how the melodic germ cell e-flat' - d' is taken up and continued in the continuation.

Richard Wagner, on the other hand, regarded the first two bars as a self-contained motif with its own expressive power. He expresses this view in his writings About conducting and About writing and composing operas. Schenker quotes the relevant passage from the first work, which is reproduced here in full: "Now let us suppose that Beethoven's voice called out to a conductor from the grave: 'Hold my fermata long and terribly! I did not write fermatas for fun or out of embarrassment, for example, in order to reflect on what comes next; rather, what in my Adagio is the tone to be absorbed completely and fully for the expression of indulgent emotion, I throw the same, when I need it, into the violently and quickly figured Allegro, as a blissful or terribly persistent spasm. Then the life of the sound is to be absorbed down to its last drop of blood; then I stop the waves of my sea and let it look into its abyss; or I stop the flow of the clouds, disperse the confused streaks of mist, and let it look once into the pure blue ether, into the radiant eye of the sun. For this purpose, I place fermatas, i.e. suddenly entering notes that can be sustained for a long time, in my allegros. And now note what very specific thematic intention I had with this sustained E flat after three stormy short notes, and what I want to have said with all the notes to be sustained in the following."

Wagner thus places his interpretation close to the metaphor handed down by Anton Schindler, according to which fate knocks at the gate. Schenker counters this with the following reply: "Even if it were the case that the rhythm of the motif in the master's imagination had created the idea of fate knocking at the gate, then beyond this knocking, it is only art that does its work, no longer fate. And if one also wanted to interpret hermeneutically that Beethoven wrestles with fate throughout the entire movement, then not only fate alone would be involved in the wrestling, but also Beethoven, and not only Beethoven the man, but even more so Beethoven the musician. So if Beethoven ranks in tones, then none of the legends and no hermeneutic interpretation will suffice to explain the world of tones if one does not think and feel with the tones in the same way as they think themselves." (italics added by the author).

This expresses two fundamentally different aesthetic principles. Schenker interprets the music from the inside, so to speak, he is interested in the structure and tries to understand the music from this insight. He is by no means closed to expression, but he leaves the determination of content to the listener. As he does not want to influence this, one searches in vain for such clues in his analyses. What interests him about a work of art is not what it is, but how it is made. The more precisely the manner of making can be recognized, the more precisely the expression and the perception will be based on it. Schenker thus understood the relationship between structure and expression in the same way as Helmut Lachenmann once described it: "And that is a constructive will that deals with things in an ordering or decomposing way. Everything a composer does, everything he constructs, is subsequently transferred as expression. For me, the term structure is just the reverse side of what we as listeners call expression."

Example Bach

Wagner, on the other hand, is primarily interested in expression. A piece has opened up or revealed itself to him (to use a Wagnerian term) as soon as he has experienced its expression. In this respect, a description in About conducting of interpretations from the Well-Tempered Clavier by Bach. The poet-composer describes a performance of the Prelude and Fugue in E flat minor from WTC I (Wagner does not mention the D flat minor key of the fugue) by a well-known older musician and comrade of Mendelssohn. This prelude seemed so harmless and meaningless to him that he felt he had been transported to a New Hellenic synagogue. In order to rid himself of this embarrassing impression, he once asked Franz Liszt to perform the Prelude and Fugue in C sharp minor for him. He describes his impression in the following words: "Now I had known what to expect from Liszt at the piano; but what I was now getting to know I had not expected from Bach himself, however well I had studied him. But here I saw what all study is in contrast to revelation: Liszt revealed Bach to me through the performance of this single fugue, so that I now know unmistakably where I stand with him, from here I can measure him in all his parts, and can resolve every misconception, every doubt about him with strong faith."

It is very remarkable that Wagner allows Liszt's playing to reveal Bach's music to him, while his own study of the compositions of the master from Eisenach is of secondary importance. In this example, he did not draw what the music had to say to him from his own knowledge, but let an interpreter who suited his taste give him the message.

The recognition of structure is often seen as the enemy of expression and a restriction of artistic freedom, although these two poles could be mutually dependent and mutually beneficial. In any case, I have always found that it is the recognition of structure that ultimately makes the beauty of a composition possible. Without this work, I can certainly find art enjoyable, but that is not the reason why I am interested in it. In any case, Heinrich Schenker's method of analysis is a great help to me in experiencing the beauty of music, whereby beauty is seen here as a game, how the different structural levels are in conversation with each other and how complexity is reflected in unity and vice versa. If you want to put it to the test, you can read the short essay The art of listening from the third issue of The will to sound to deal with. I am convinced that the quality of the perception of the first four bars of Bach's Prelude in F sharp major from WTC I, which is discussed in the text, is enhanced by the voice-leading relationships described. However, when reading the text, one will discover another trait that Schenker shares with Wagner, namely the penetrating way in which he always denigrates those who think differently. For both of them, however, this seems to me to be more of a protective armor under which their work was able to flourish.

In the essay just mentioned, it is Hugo Riemann who is the victim of Schenker's tirades. Even if this way of expressing himself is repulsive because it is absolutely unnecessary and does not serve the cause, Schenker is not wrong. In his Catechism of Fugue Composition, Riemann describes all the preludes and fugues from J.S. Bach's WTC. To add another example, I have chosen the Prelude in C minor from WTC I. Riemann characterizes this piece entirely from a Romantic perspective. He uses metaphors that are reminiscent of Beethoven's 5th Symphony and the Grande sonate pathétique op.13 were formed. For him, the piece is born entirely from the spirit of the C minor key, full of restrained power and vibrating passion. In the Presto section, he even speaks of a pelting hailstorm breaking loose. It is possible to arrive at such content-related statements without having to understand anything about structure, compositional technique or voice leading. Nor do they testify to an in-depth examination of the piece, but are an expression of an external determination of content. In this way of dealing with art, expressivity is not extracted from the object, but is grafted onto it, as it were.

Concluding remarks

The purpose of an anniversary year can also be to draw attention to what has been hidden and buried. In the case of Richard Wagner, for example, it would be to rethink and reflect on the still prevalent Romantic conception of music - despite historical performance practice.

Friedrich Schiller writes in the 23rd letter of his Letters On the aesthetic education of man The following thoughts: "In a truly beautiful work of art, the content should do nothing, but the form should do everything; for the form alone has an effect on the whole of man, whereas the content only has an effect on individual forces. The content, however sublime and far-reaching it may be, therefore always has a restrictive effect on the spirit, and true aesthetic freedom can only be expected from the form."

Schiller, who - like Goethe as a naturalist - is, in my opinion, under-appreciated as a philosopher, developed the philosophical foundation for a theory of Heinrich Schenker's caliber in his aesthetic writings. True aesthetic freedom is to be expected from the knowledge of form, i.e. from structure, and not through the mediation of content. The task would therefore be to understand structure not as an abstract concept that is perceived as devoid of content and emotion (or even as an enemy of expressivity), but on the contrary as a trigger for the infinite variety of the emotional world. At this point, both the practical and the theoretical musician are called upon, the former insofar as he reflects on structures as the basis of interpretation and the latter through a type of mediation that consciously thematizes the relationship between structure and content.

Just how modern Schenker's thinking was can also be seen from the fact that, at a time when it was fashionable to cover editions of classical works with interpretative indications such as slurs, dynamic markings etc., he decided to reflect the composer's intentions as far as possible by dispensing with all these ingredients as an editor and reproducing the musical text as authentically as possible.

Raphael Staubli is a lecturer in theory at the Lucerne School of Music.