Music for eyes and head

At least since the musical avant-garde, music graphics have been considered a genre in its own right between visual art and music. What does this kind of silent music look like in the digital age? And what can it achieve? An investigation using the example of Johannes Kreidler's "sheet music".

At least since the musical avant-garde, music graphics have been considered a genre in its own right between visual art and music. What does this kind of silent music look like in the digital age? And what can it achieve? An investigation using the example of Johannes Kreidler's "sheet music".

While browsing in the souvenir store, my eyes fall on a postcard: a line of music that runs across the entire width of the card. There is a treble clef at the beginning, otherwise it is blank. "Enjoy the peace", reads the caption. It reminds me of a series of black and white prints, the sheet music by Johannes Kreidler, which follow exactly the same pattern: a graphic of music symbols with a title, the principle of minimalism, as in the sheet Sunsetwhich consists of only one stave and a single note.

Although the postcard motif is nice and somehow sophisticated, it still looks pale against the background of Kreidler's works. The sheets obviously have something that the postcard does not, but which remains hidden at first glance. But what?

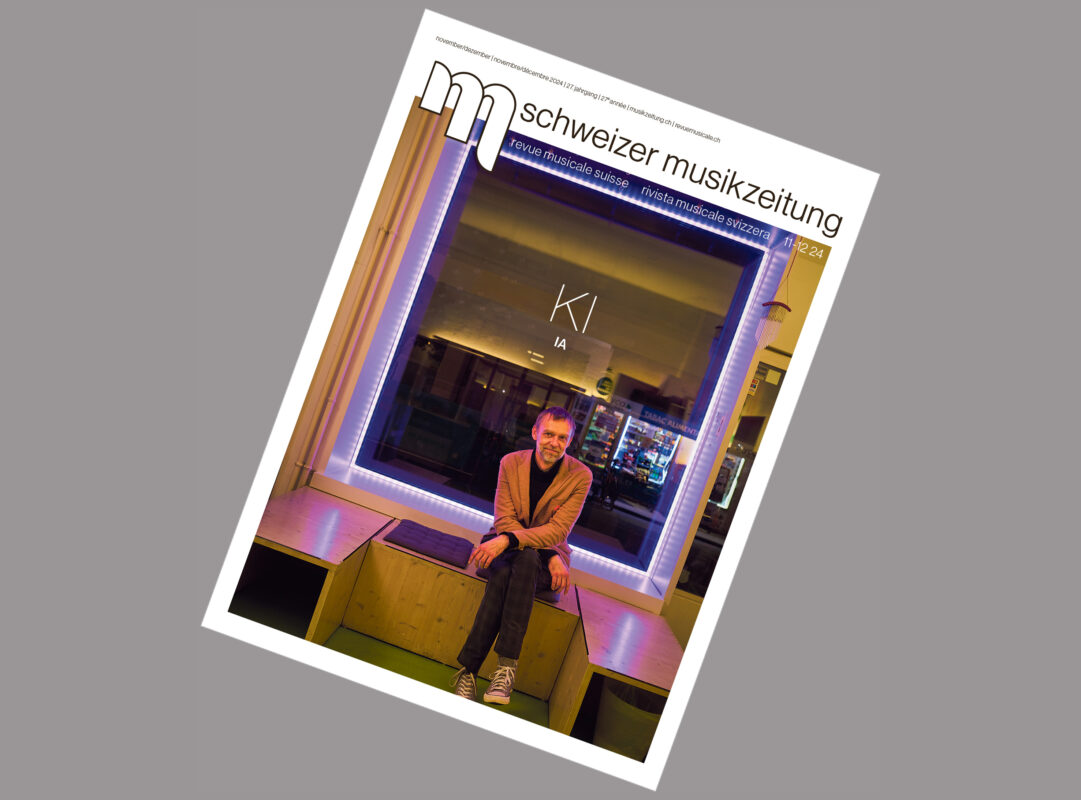

The key to this lies in its origins: its creator is not a graphic designer with a particular flair for originality, but an artist, performer and, above all, a composer. In recent years, Kreidler has repeatedly attracted attention for his innovative and provocative works and actions, which he always places in a theoretical context. New conceptualism is the catchphrase under which the 34-year-old understands his current work and on whose soil the sheets are also planted. What counts is the idea, for the realization of which all means and media of art are permitted. How and whether it sounds is secondary. With the sheet musicwhich Kreidler has been creating since 2013, he completely turns away from the audible: He composes graphics from sheet music, "eye music" - and that too with a concept.

As far as the material is concerned, this concept is very simple: white background, black font, type: Times New Roman, a triad with title 1+2=3without frills. The postcard contradicts this with its red, italicized slogan, which reveals that it wants to be pretty. The sheet music doesn't want that, at least not only. Above all, it wants to communicate something, and the viewer generates this communication himself by relating the two layers of signs to each other. 1+2=3 does not actually show a triad, but notation symbols that we call a triad because of their arrangement and the title. The title sets limits to the scope for association, a principle that Kreidler already applied in a similar way in his action External work tested. There, he influenced auditory perception by always playing the same music with different introductions. He called this "prepared hearing", and here he provides the counterpart: "prepared seeing".

- Johannes Kreidler

- "Sunrise for Bejiing" (2014)

The postcard works in the same way: the image and title make a statement that is relatively easy to grasp and unambiguous. Once we have understood it, we look away. The sheets, on the other hand, hold our attention through their individuality, openness and mysteriousness. Their interpretation is not only a cognitive but also a creative achievement. Each sheet provides food for thought that can lead in very different directions. Only irony forms a continuum, as in the sheet Sunrise for Beijing. A few graphic elements, in combination with the commentary that accompanies the sheet on Kreidler's blog Cultural techno adds, as a cocktail of gallows humor and social criticism: "Because of the extreme smog, the image of a sunrise is shown on a large LED screen in Beijing."

However, most of the sheets lead thematically back to the origin of the small forms. "I want everyone to think about music now!" What Kreidler demanded in one of his performances also applies to the sheets. They take up topoi from music history, process them in a playful way and expand them with subtle punchlines, such as Tristan Motive, altogethera cluster that unites all the notes of the Tristan motif - Kreidler's contribution to a never-ending debate in music theory.

Ultimately, the prints as a whole can also be understood as reflections on the digital tools of today's composer. The mass accumulations of notation symbols in the sheet series Deposits stand for the limitless availability of the material, which nowadays seems to be better stored in graphics than in scores. The sheets introduce us to the software both as a tool that facilitates notation and makes it easier to communicate, and as a medium that creates a distance between author and notation. The seemingly arbitrary composition of musical notation, e.g. in Beach Gamehas symbolic status: the composer is no longer the master of what he enters into the computer.

But Kreidler has his notes under control: he deliberately moves signs to create awareness. He composes, just not sounds. Is sheet music music at all? An almost philosophical question, to which Kreidler takes a clear stance: "Music also has to get out of the time-base. Music is not only acoustic, it also has its [sic!] visual contexts. It is then still music." In fact, only a few of the images suggest an acoustic moment. Kreidler's answer belies the complexity of the matter, just as many a sheet belies the serious thoughts of its relatives: a line of music that stretches across the entire width of a canvas. There is a circular note in the fourth space, otherwise it is empty. "Asshole", reads the caption. Provoke - the postcard cannot do that either.

sheet music under